The Carter Family Right Down in Your Blood

|

Justin Panson

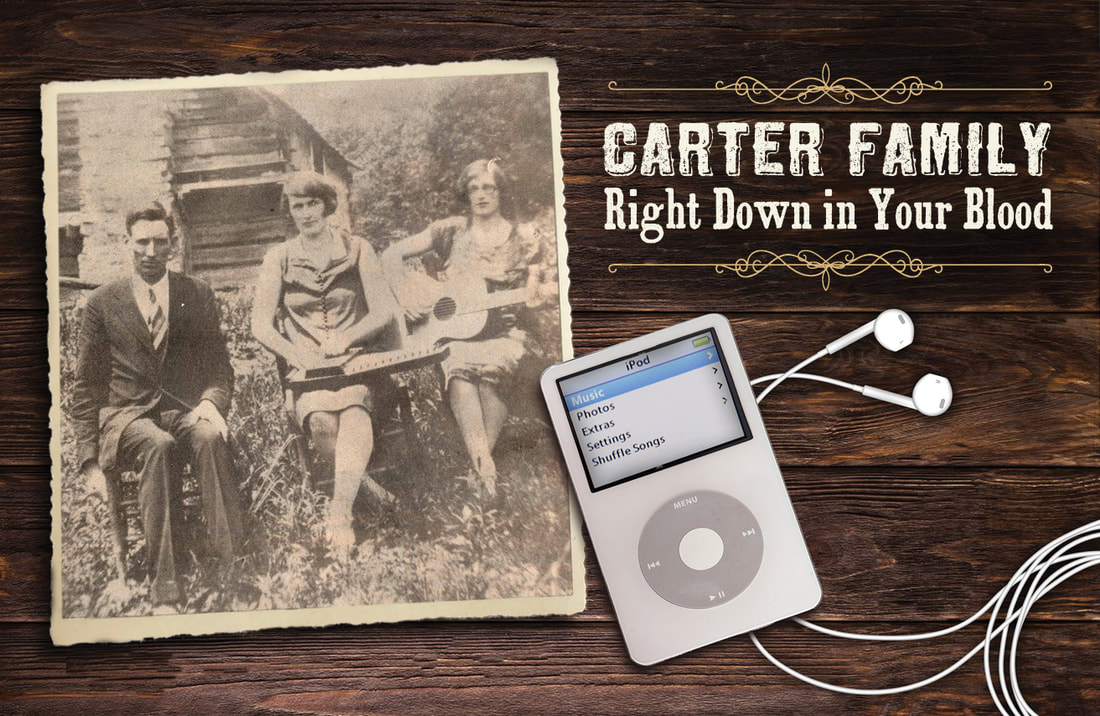

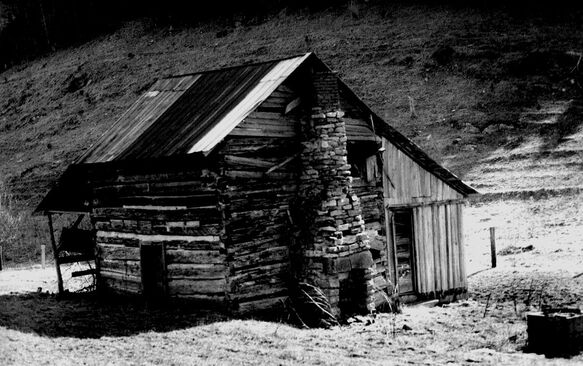

I came across my old iPod the other day buried in a desk drawer. It was like unearthing an artifact from the primitive times before Spotify, when I carried this little silver totem everywhere, just happy with the miracle of a whole record collection in my pocket. Nothing like nostalgia for technology that’s only a few years dead. For kicks I charged the thing up and plugged it into the car stereo on my commute. Shuffle mode is the Russian roulette that gets you off your current playlists and dredges up forgotten bands from past musical affections. Out of nowhere, a Carter Family tune came on, a song called Gold Watch and Chain, in which the singer expresses a lovelorn angst, vowing to his betrothed: “I will pawn you this heart in my bosom, only say that you love me again.” Racing down the highway at 70 mph, I was struck by the remote, antique quality of the song, a little hokey, but at the same time piercing in its lonesome, plaintive sincerity—a sound that summoned ghosts out of the gothic past, a stripped down sort of mountain gospel music that just doesn’t exist in our era. This timepiece played in sharp contrast to the rest of the songs of that morning: the swaggering hip hop, the self-involved emo crooners, the love ballads of teenage heartbreak, all the power chords and pop hooks. At first, this hillbilly song seemed so out of line with everything else. But as I considered it later, I realized if you are living in the US of A, then this seemingly dumb, raw hillbilly music is right down in your blood. This chance discovery prompted a deeper dive into the Carter story, and the more you read the more you realize it’s a story out of a cliched Hollywood Cinderella movie, one of the really great American stories! You couldn not have scripted it better if you tried. Back in the late 1920s this clan lived in a harsh, unforgiving world, a remote and isolated part of rural Virginia. They were God fearing true believers who scraped by season after season in a subsistence economy, working the same rocky, sub-par land their families had worked since the Revolutionary War. This low down remote life ended up giving their sound a purity that to this day remains singular. At the center of the story is A.P. Carter, Alvin Pleasant Delaney Carter, a lanky guy with sunken haunted eyes, an awkward, remote man with an air of tragedy about him. Genius is one of these overused terms in our self congratulatory culture. But there isn’t a better word for A.P. Carter. He heard things nobody else heard, and knew how to capture what he heard, arrange it, perform it and sell it. He valued the everyday music that his contemporaries took for granted. Like other visionaries, this man forsaw the world before it happened — and then had the ambition and know-how to make that world happen.

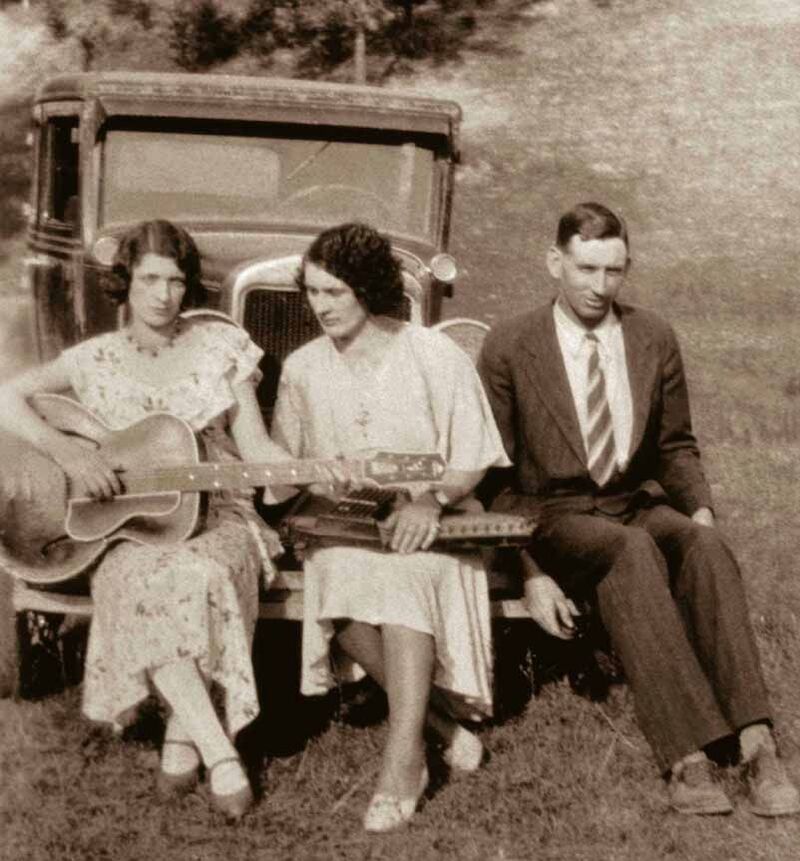

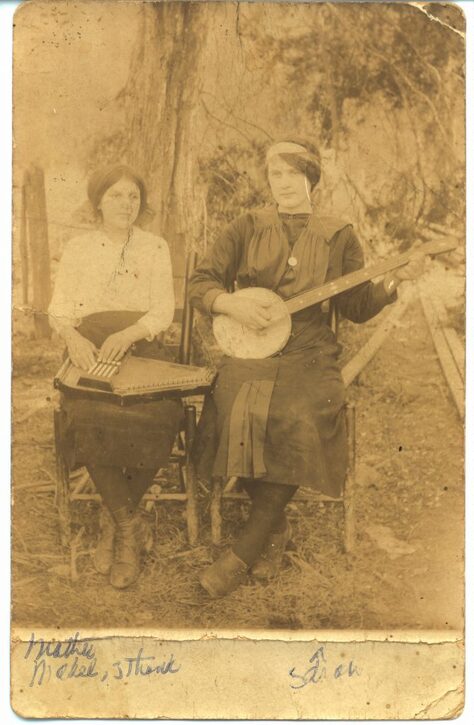

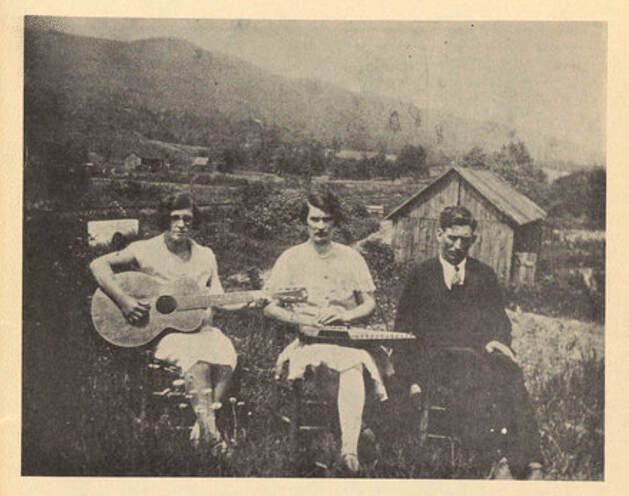

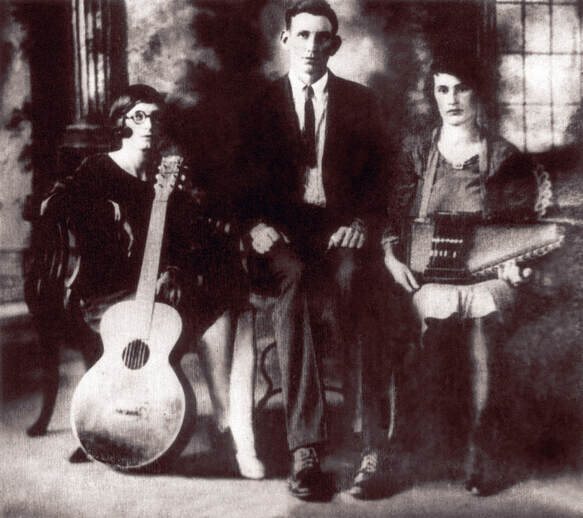

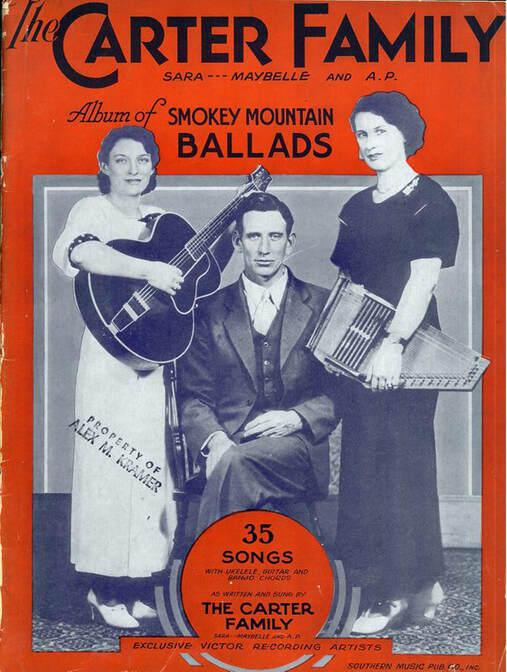

So the story goes, A.P.’s mom was hit by a bolt of lightning when she was carrying him, and she prophasized that the lightning strike was a divine intervention that accounted for her son’s odd, tremors and shaking — and his unique abilities. Moms know. As a young man he was a loner, wiling away countless hours walking the railroad tracks, and trying to make a go of various occupations. But then it turns into a love story. He was selling fruit tree seedlings door-to-door when he approached his aunt’s house and heard what he later said was the most beautiful singing voice he had ever heard. This was Sara, an orphan living with A.P.’s aunt. There was a depth and a power in her voice. It had a piercing quality that cut through to a deeper place. She was singing Engine 143, her somber delivery eerily perfect for the tragic story-song of a kid killed in a train wreck. Music connected A.P. and Sara, and before long, they were married, or by hill country vernacular they “jumped the broomstick.” Sara was solitary and self assured. She was a liberated woman before there was such a thing. She hunted and fished and wore pants and smoked cigarettes and danced and didn’t give a damn about what anyone thought. A.P. and Sara would be joined by her first cousin, Maybelle, who played autoharp, banjo and guitar. She was a self-taught savant, a natural musician who could hear a tune and just play it in her own way. From listening to relatives play all of her life she knew hundreds of traditional songs, many of which she didn’t even know the names of. From the Carter biography (1), a young folk revival admirer said, “I will never forget watching Maybelle, the way she moved her hands in simple little elegant, graceful gestures, making this incredible sound come out of that Gibson. It reminded me of the way my grandmother used to crochet...everything about Maybelle was unpretentious and matter-of-fact.” Together these two women were formidable and independent decades before women’s liberation. A.P. would hang aloof on the side and chime in sometimes and sing on some of the numbers, his tremor giving his voice a spooky, quivering quality. He began to “collect” the traditional songs from their local area and rearrange them, adding lyrics and his own sense of artistry.

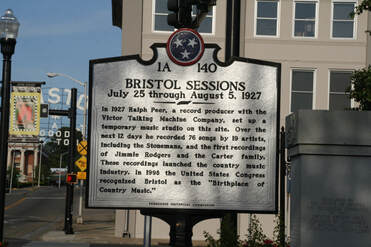

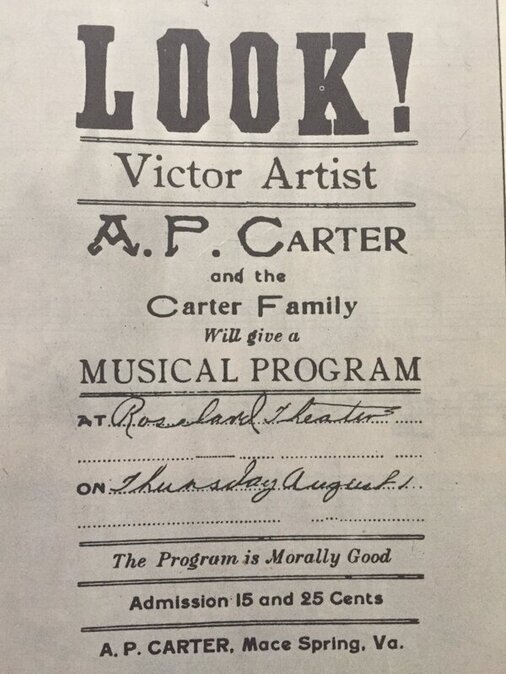

The fledgling trio began to play locally, in barns, on porches and in the tiny shotgun shacks, where they took the furniture outside to clear space to dance, playing traditional and square dance songs often until the sun came up. Their tight harmonies became well known in their little corner of southern Virginia. When word got out that they were going to play, people just showed up from all across the area. The way the Carters got discovered is one of those long shots that's just hard to imagine. One day A.P. saw an advertisement for open call tryouts for musical acts being held in Bristol, Tennessee. He borrowed a car from his brother and managed to convince his 8-months-pregnant wife and her cousin, who were not at all interested. They barnstormed out of the hills of Virginia in the scorching August heat, with Maybelle’s infant son crying the entire way. They traveled over very rough hill roads in a beat-up old jalopy that kept getting flats. They had to cross creeks, driving all day to get twenty miles to the Tennessee border. This sort of open tryout was one of many throughout the mid Atlantic region, to find talent for the emerging Victrola phonograph and radio technologies—to find “content,” as they say today. Content was king then, and still. Technology creates the format, then the producers scurry around looking for stuff to fill it with.

The Carters finally made it to the tryout. On the second floor of an abandoned hat factory two women and a man stood up before the double-button carbon microphone and let loose their high-register, plaintiff, harmonies. The two songs they sang that day blew the music promoter away, and launched what would become one of the greatest runs in the history of American music in terms of records sold, fame and cultural significance. That music promoter was an empresario figure named Ralph Peer. “As soon as I heard Sara’s voice, that was it.” he said. He would later express his amazement that “they were good, but they didn’t seem to know how good they were.” The first song they sang, (Bury Me Under the) Weeping Willow, is a maudlin saw of a tune where a spurned lover contemplates her own demise. The creaky recording is just devastatingly emotional, the rugged and enduring quality of Sara’s voice. In a recording of it many years later, Maybelle added a little narrative at the end where she describes what it was like listening to the recording played back for the first time on the Victrola device. What a moment, like a primitive human seeing their image in a mirror for the first time. There is one little detail that is absolutely essential about the audition story. When the three of them showed up and saw the fancy people in the lobby they were ashamed of their raggedy clothes, so they went up to the second floor via the fire escape. That deep country humility translated directly onto the acetate record they cut that August day 93 years ago. Shortly after that audition their music swept across a country hungry for their style of homespun, authentic songs. The Carters quickly became the first national music sensation — along with Jimmie Rogers, who also had laid down tracks at Bristol. The radio is what drove their fame. In much of the country there was little else to do but sit around the radio in the evening, and in this way people welcomed the Carters into their homes. Their music gave people a reason for hope and a point of connection. The Carter Family had a way of making the forgotten feel a sense of belonging. They were the real deal, singing about their own story. Ralph Peer scheduled additional recording sessions where they flawlessly laid down track after track, assembling what would become the foundation of country music. Within a few years they had sold over 300,000 records, a big number at that time. Their songs had drama and weren’t afraid to deal with the darker side of life, the stuff people don’t acknowledge, universal themes that mixed hope and tragedy, and resonated with so many rural people struggling through the first years of the Great Depression. The Zwonitzer / Hirshberg biography put it this way, “The Carters had a way of giving voice to that unspoken dread...in such early recordings as Will You Miss Me When I’m Gone was the sound of a single person facing down the desolate emptiness of an uncaring time, a distant, ghostly cry from the darkest hollows...Songs with sharp edges, a clear eyed look at love, loss, hurt and longing, an unwavering look at hard living and personal pain….” Although the relentlessly positive Keep on the Sunny Side would become a trademark song, many of the lyrics and stories could be very dark, even by today’s debased standards: If the Light is Gone Out Your Soul; Wouldn't Mind Dying, Ain't Got No Home in this World…to name just a few. And then there were the murder ballads, like this one, Gathering Flowers from the Hillside: I know that you have seen trouble But never hang down your head Your love for me is like the flowers Your love for me is dead It was on one bright June morning The roses were in bloom I shot and killed my darling And what will be my doom? That’s some straight-up gangster shit.

As the Carters’ star rose, A.P. realized they needed more songs to record, beyond the traditional numbers they knew from the vicinity of Poor Valley. There was a financial reason for new source material, based on copyright law. The Carters got paid for each song on each record sold because A.P.'s song arrangements were original. In order to continue generating revenue, he needed more songs.

So he began traveling to towns and hamlets across southwestern Virginia on “song fetching” trips, rambling across the hill country and territory of several states, looking for traditional songs from all over the Appalachian Countryside. His obsession took him down dirt roads and onto porches and into general stores, meeting people and listening to them play. On one trip he met a black musician named Lesley Riddle who became a partner on these missions. Riddle couldn’t read or write, but he had an uncanny ability to remember lyrics and melody, transcribing them out of thin air. He recalled, “I was his tape recorder...he’d take me with him and he’d get someone to sing him the whole song. Then I would get it, then I’d learn it to Sara and Maybelle.” This was an unlikely friendship, a gangly man with a shake and his sidekick, a one-legged black man. A.P. looked after his friend in dangerous Jim Crow country when interracial friendships were extremely rare. A.P. and Lesley could be gone for weeks at a time, out in the hollows and coal mining towns. Legend has it that he could look at a house and say, “There’s a song in there.” He’d just go up to people’s homes and say,”Hello, I was told by someone you got a song, kind of an old song. Would you mind letting me hear it?” He was rarely wrong. A.P. would often return home with scraps of paper bulging from his pockets. He overlaid his own unique arrangements on top of the traditional tunes. And from this seat-of-the-pants ethnography, the canon of American music, as we know it, was derived. His “musicology” crossed all boundaries of race, geography and ethnicity, and reached well beyond the traditions of Poor Valley. They found church house blues and sacred songs from the black baptist or penticostal churches, songs of an existential loneliness that white anglo music didn’t reach. The mountain sound and its related sub-genres is a unique mash up of African, Celtic and aboriginal sounds, featuring some combination of fiddle, banjo, guitar, autoharp, dulcimer and standup bass. Some songs feature the Austro-Bavarian technique of yodeling, which had been popularized in the States by traveling minstrels in the generation prior to the Carters. The musical mashup of the Carter sound tracked with the larger cultural mashup of the young nation, the messy, complex, beautiful melting pot. A.P.’s drive and singular genius carried the songs of his remote region to the wider world and, in effect, channeled rural America itself. Then there is the musicianship. The Carters were technical innovators, especially Maybelle who invented a unique thumb brush guitar technique that came to be known as the Carter Scratch. She would play the melody on the bass strings, while at the same time rhythm strumming on the treble strings above. This innovation came out of the necessity of not having someone to play the rhythm part. It produced a distinctive full sound that carried the emotion of their songs and helped the guitar become a lead instrument.

Maybelle’s daughter June Carter Cash described it this way, “She’d hook that right thumb under that big bass string and just like magic the other fingers moved fast like a threshing machine...and out came the lead notes and the accompaniment at the same time...and the guitar rang clear and sweet with a mellow touch that made you know it was Maybelle playing the guitar.” Maybelle was self-taught on the autoharp, banjo and guitar from a very early age. The autoharp was too big for her initially, but she became proficient on it by the time she was a teen. Sara’s powerful singing, Maybelle’s innovative playing, and A.P.’s curation of the canon was a unique and powerful combination. There's heartbreak at the center of the Carter Family family story that is captured in their lovelorn songs, and to this day is carried forward as an essential subject matter of country music. With A.P. out on the road chasing new material for weeks at a time, Sara was left to manage the household and kids. She bore this and A.P.’s remoteness in her stoic, unsentimental way. But the marriage strained and a shadow of unrequited love and melancholy crept over them.

Sara eventually fell for another man in Poor Valley, named Coy Bayes. An affair like this in a close knit town of a few hundred people was pretty scandalous. So a solution was brokered whereby Coy and his parents would move away to California. In 1933, Sara, a fiercely independent and enigmatic woman, left A.P. They divorced three years later. But the money and success were too good to break up the band, so Sara agreed to continue recording and performing with her estranged husband. Like a lot of family dysfunction, theirs was hidden behind a facade, a stage act where they presented an image of family and domesticity at odds with their real lives. A.P. never got over the breakup, living out his days as a broken man, still playing music with his ex-wife.

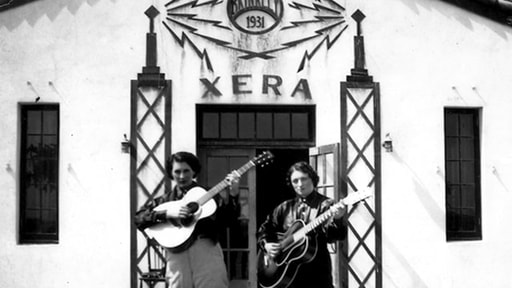

The breakup of A.P. and Sara set the stage for this absolutely crazy story in which Mexican border radio was the conduit of true love. In 1938 the band had gone down to play an extended stint at the Texas border radio station XERA. At that time, powerful stations were set up in Mexico just across the border radio to evade US law restricting broadcast range. XERA’s signal reached from New York to California and up into Canada. This was probably the first national broadcast media.

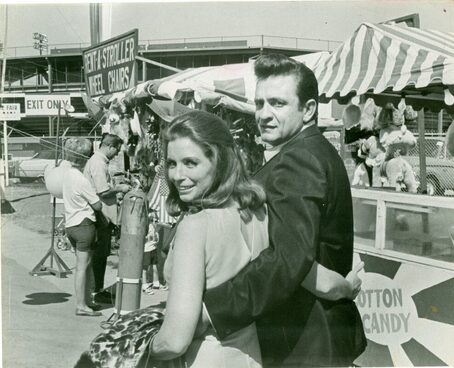

With all our forms of media today we can’t grasp how important radio was back then, serving as a thin connection between people across the desolate miles in a country still rural and otherwise unconnected. Waylon Jennings told the story of his father hooking the radio up to the car battery so his family could huddle around and listen. And another one about Johnny Cash when he was a boy listening to the child performer June Carter and saying he would marry her one day. There are so many stories in this regard about people for whom the radio held their wonder, hopes and dreams. The Carters were pros at this point and quite famous. They were banging out two coast-to-coast shows every day on XERA peppered with all sorts of cornball skits and sponsor tie-ins. All the while Sara was missing her lover, Coy Bayes. She had been writing to him for six years with no reply. One night out of nowhere, she stepped to the microphone, with her ex-husband standing right there, and dedicated a song to her friend Coy Bays in California. It was an traditional Irish ballad of lost love called I’m Thinking Tonight of My Blue Eyes. Would have been better for us both had we never In this wide and wicked world had never met For the pleasure we've both seen together I am sure, love, I'll never forget Oh, I'm thinking tonight of my blue eyes Who is sailing far over the sea Oh, I'm thinking tonight of my blue eyes And I wonder if he ever thinks of me It went out across the continent. Coy Bayes, like so many thousands of people, was tuned to XERA’s evening program. He heard Sara calling out to him 1,200 miles away. For six years he didn’t answer her letters because they had been intercepted by his mom. Coy told his parents that he was going to go get Sara, and then he drove through the night and straight down to Texas. They were married within three weeks. She left the band and moved with Coy to California, leaving her children with A.P. and relatives in Poor Valley. Think of the pain and complexity of leaving your children like that. Sara and Coy lived together in relative obscurity, a marriage would last for the rest of their lives. Over the decades only occasionally was Sara ever coaxed into playing music again. |

In the late 1930s wIth Sara Carter effectively retired from the spotlight of professional music, Maybelle took her talented, precocious daughters on the road, continuing and expanding the family act. For decades they performed an often grueling schedule of road shows, crisscrossing the country in cars, playing so many towns across the map and becoming regulars at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville—the pinnacle of country music entertainment. The expanded Carter Family played on other television programs, spanning into the mid-century and beyond, establishing themselves as country music royalty. They toured with Elvis and were very close with him in the years right before he skyrocketed to fame. They were close with Hank Williams too. Mother Maybelle, as she became known, tried to help him during his desperado booze-fueled decline. Her charismatic, comedic daughter, June Carter met Johnny Cash in what can only be called a fairy tale. They had one of the great show biz romances, one that survived drugs and demons, a tumultuous road life…and fame itself.

Meanwhile, A.P. Carter returned to Poor Valley alone to haphazardly run a little general store. His genius and drive had established the most significant catalog of American music, but it had cost him everything he loved. His descendants speculated that he always dreamed Sara would walk back in. In this story, everybody got what they wanted in the end, except A.P., a forgotten man when he died, a broken man, loving Sara to the end.

The extended Carter Family spawned generations of players and singers who have spread what is now generically known as “country music.” Like it or not, this includes the schmaltzy 1970s variety and today’s overwrought pop country—all the celebrations of patriotism, Jesus, pickup trucks, beer drinking, and of course love lost and found.

In a way, the Carters were pioneers of many of the current processes that remain in place in commercial music: the idea of mass distribution of shareable media (the acetate record); the idea of getting paid a royalty for each record sold; the concept of interstate touring; and the very idea of an aspirational quest for popular hits across wider geographies. Even their melding of various musical traditions is the template for today’s overlapping and intersecting genres.

Ask around today and nobody really remembers the Carters, these three obscure characters lost in the deep dark gothic past. At best, they are relegated to the realm of quaint Ken Burns Americana storytelling, a montage of grainy and obscure historical photographs. Honestly, the music itself is an acquired taste as much of it is flat, somber and a little depressing compared with today’s high-energy sound. But, be assured, no matter where you are and no matter what kind of music is pulsing through your headphones—from hip hop to Jazz to hairband arena rock to shoegaze, to dreampop to the streetwise MCs—the Carters remain the headwaters of our collective song. And as such, they are right down in your blood.

2022

(1) Will you miss me when I’m Gone?, Mark Zwonitzer and Charles Hirshberg, 2004

|

© Copyright Confluence Studio. All rights reserved.

|