|

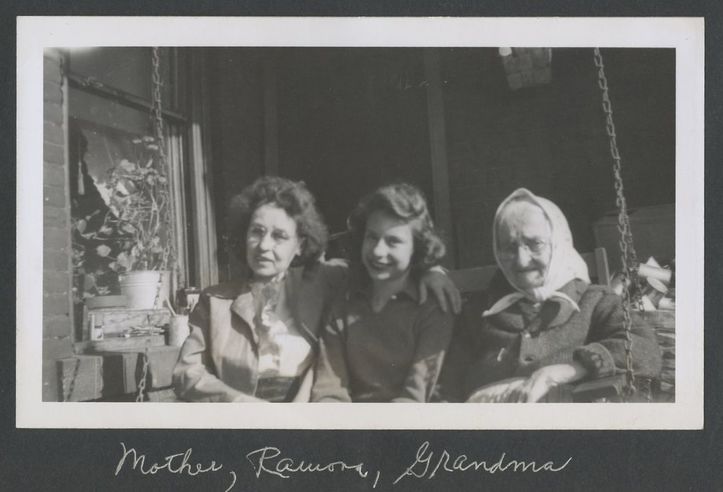

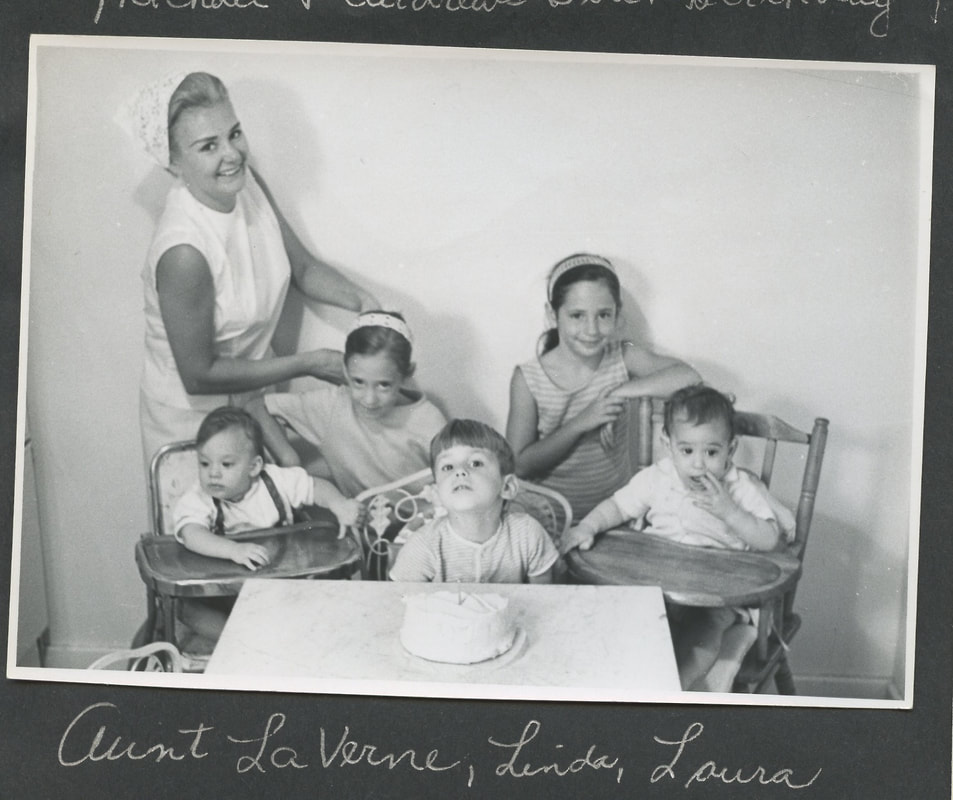

Dedicated with love to Mom, Grandma & Aunt LaVerne "Hiraeth" is a Welsh word with no exact English translation, meaning homesickness for a place or a homeland that may no longer exist. When I think about the Rust Belt Kitchen I am thinking of a mythical place that only lives in memory now, a kitchen where my Grandma, my mom and Aunt LaVerne would cook the old Croatian dishes. When grandma came for week-long visits, her cigarette smoke mixed with the aroma of sauerkraut and permeated everything, and her stern presence changed the character of the household. Grandma was a tough, bitter old woman with thick cat eye glasses, always clutching rosary beads or prayer cards. Mom and grandma would speak in Croatian fragments, low conspiratorial talk in the kitchen when they didn’t want us to understand. They cooked from scratch, what is now known by the shorthand of comfort food: Sadma, a seminal Croatian sauerkraut stew, stuffed peppers, stuffed cabbage, beef stew, and many other dishes.

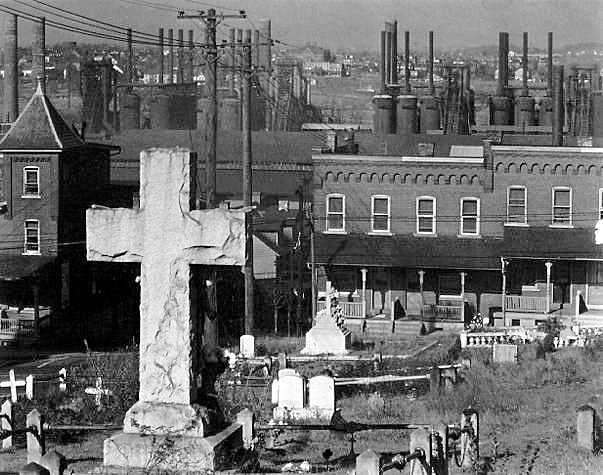

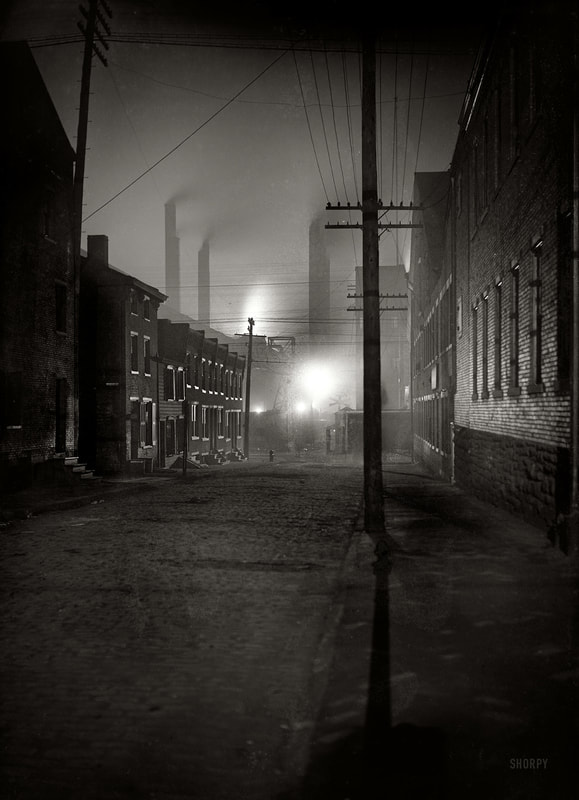

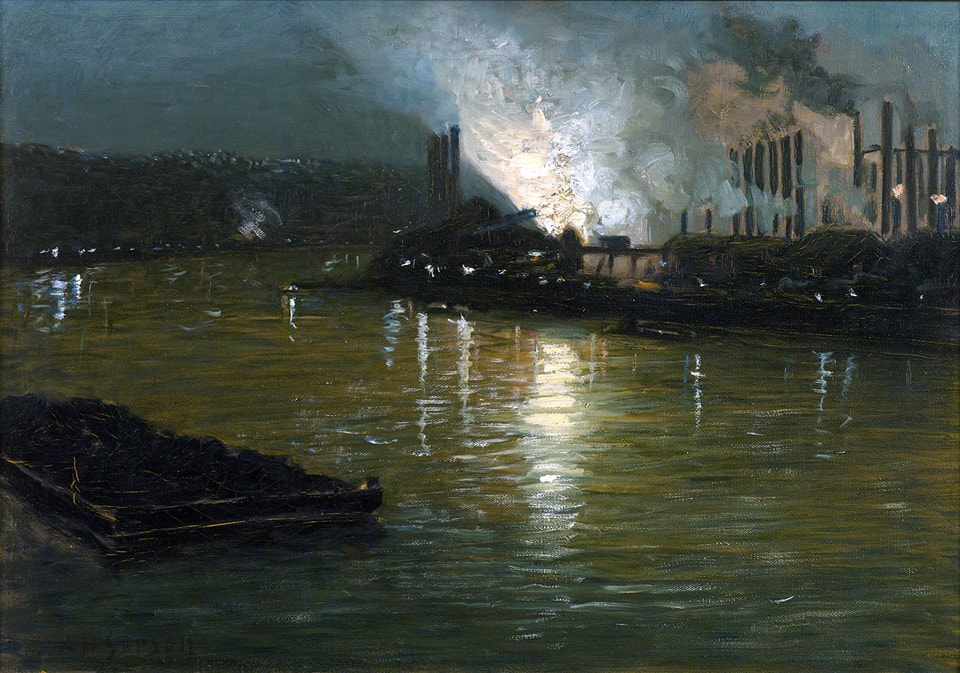

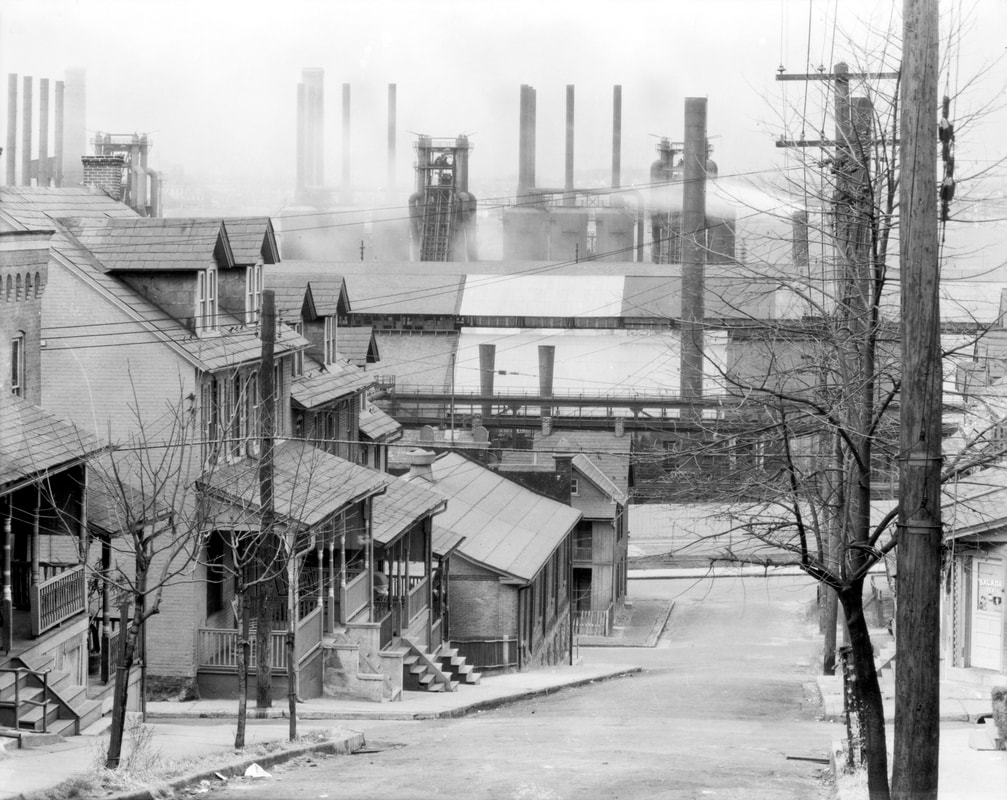

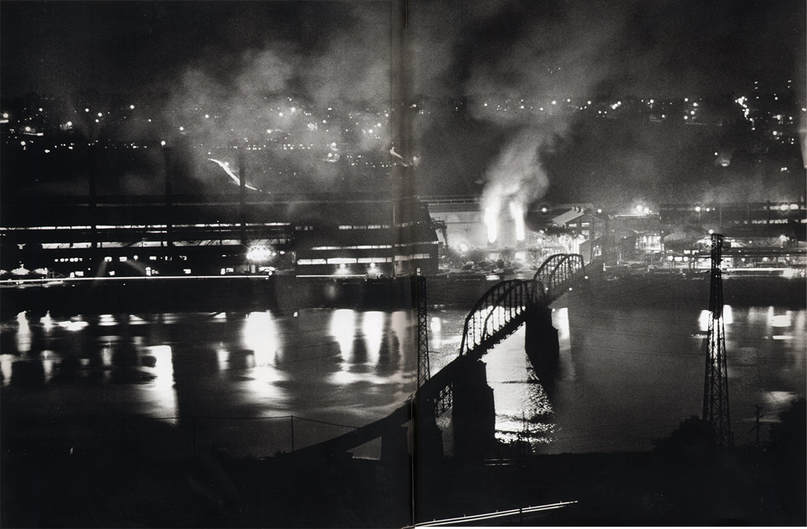

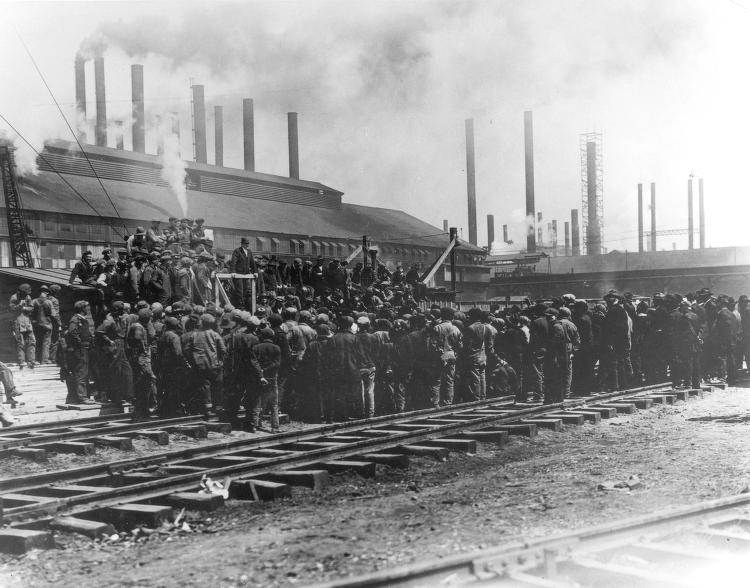

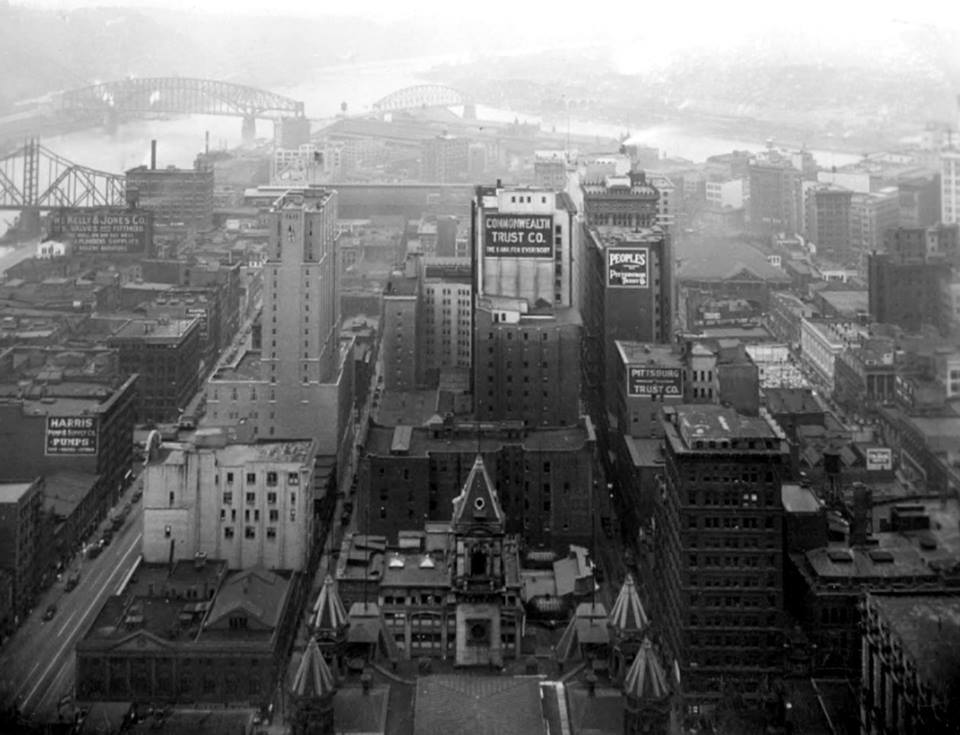

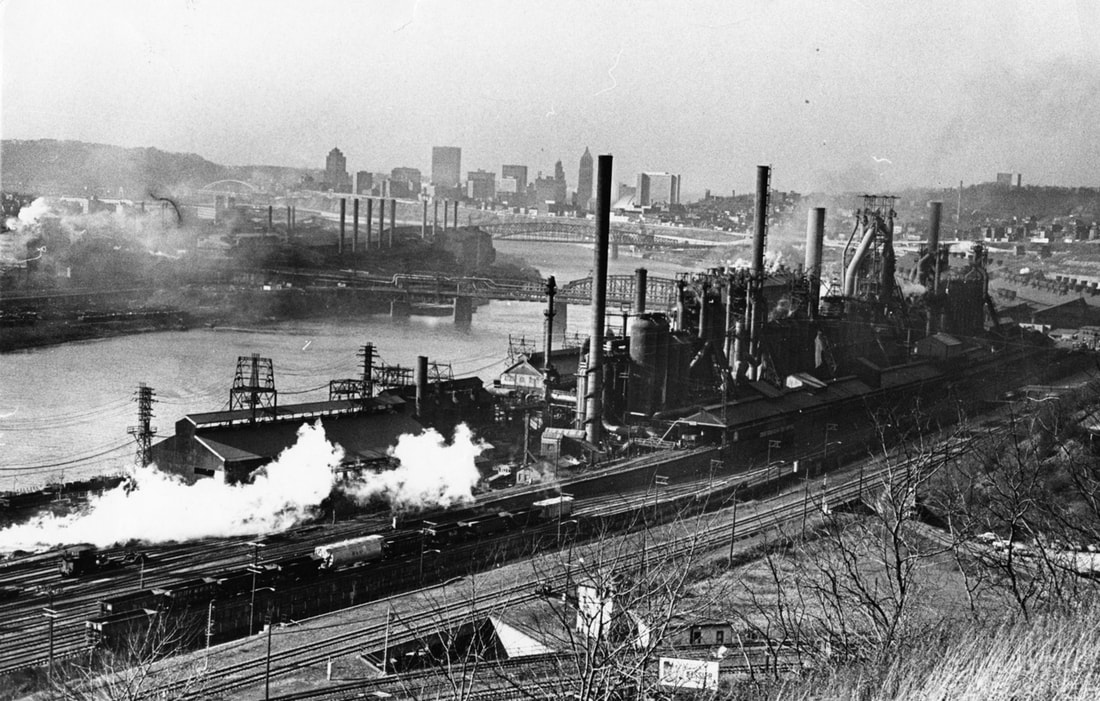

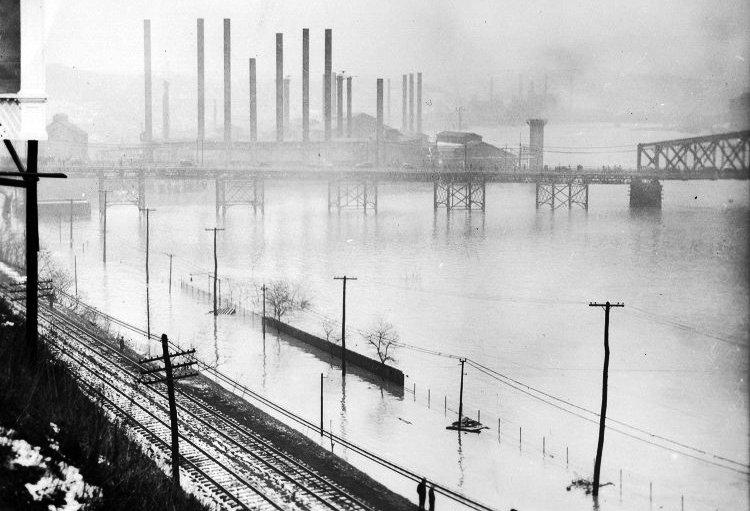

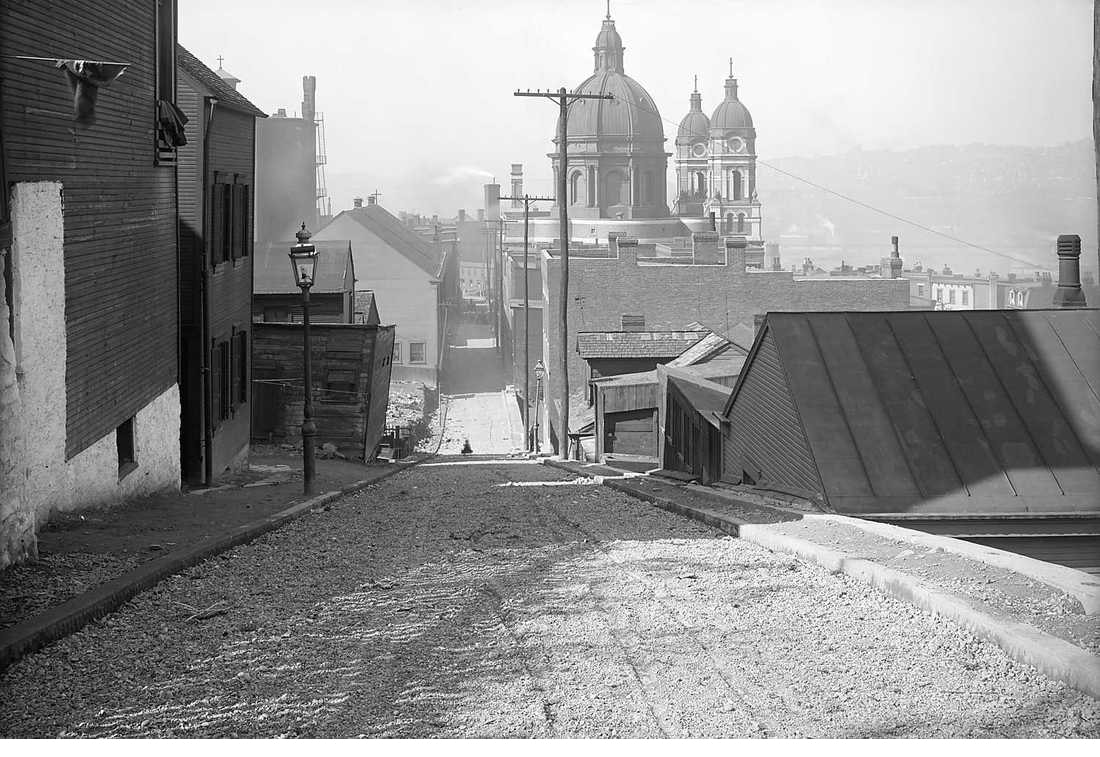

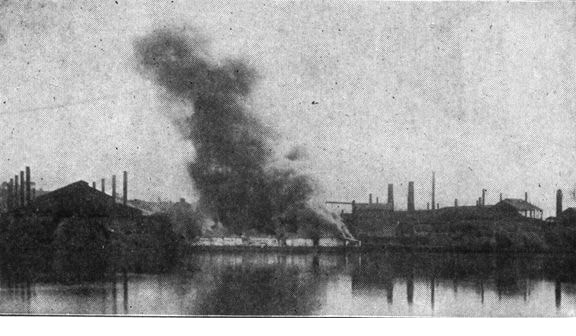

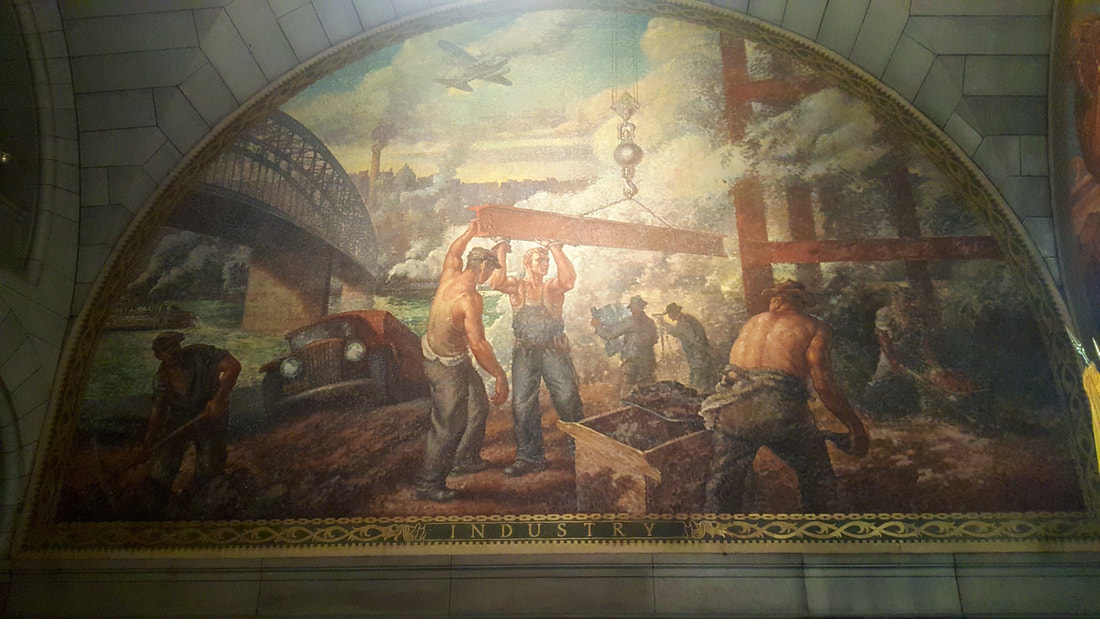

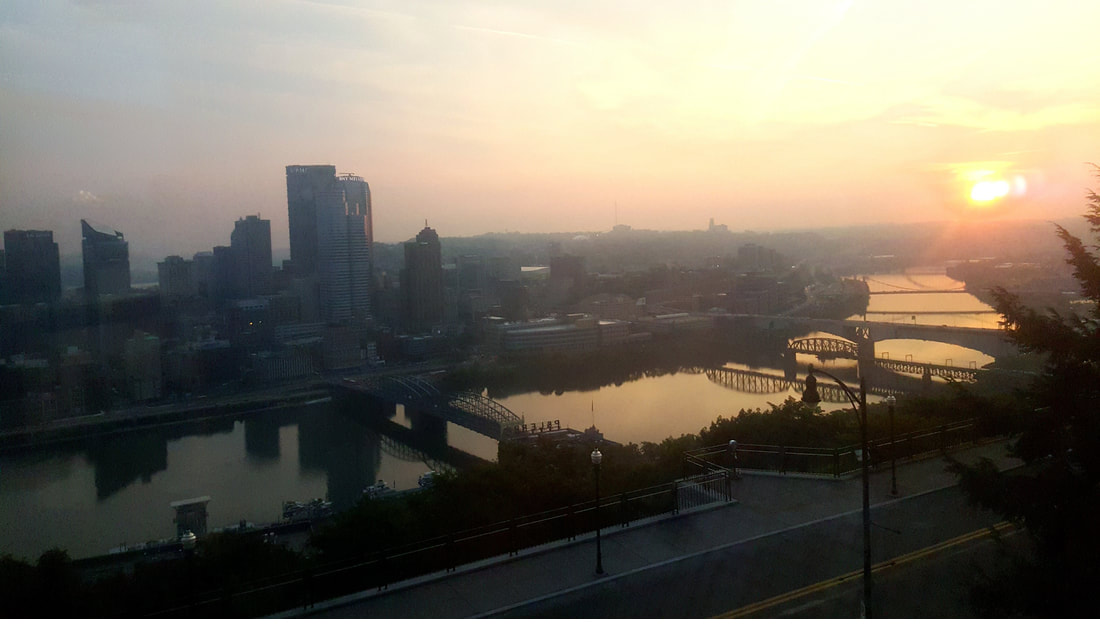

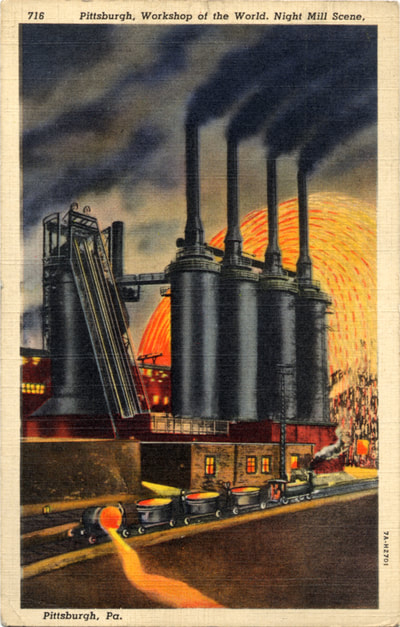

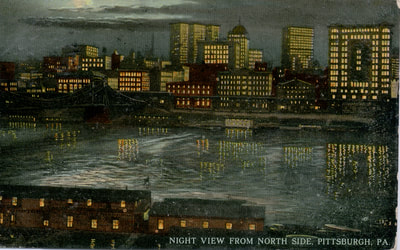

My mom knew the language because her grandma came to stay with them when mom was growing up. She was right off the boat, hailing from a little town along the Sava River near Zagreb. My great grandma remains a remote, blurry figure in the family history, but mom said on more than one occasion that she was a deeply kind woman of the old village ways. So much has been lost because I didn’t ask the questions when I had the chance. My mom is gone, and she took a lot with her. Today, a lot of the rust belt itself is gone too, the industrial age crucible that was Pittsburgh, albeit romanticized in my own imagination. It was a cultural and culinary crossroads of so many ethnicities—central and eastern Europeans, Slovaks, Jews, Italians, Germans, Ukrainians, African Americans—all living in an old, dark, smoky landscape of mills, hulking factories, railroads, brick row houses lining the hillsides. The neighborhoods were full of corner taverns and churches, coal miners and steelworkers, ladies in babushkas getting on and off trolley cars. You look at the old black and white photos and you see thick smoke drifting among the factories and buildings, blocking out the sun--it seems like some kind of ominous film noir dreamscape. It’s a visually striking town of rivers and bridges, set at the confluence where Allegheny and Monongahela rivers birth the mighty Ohio. It was Indian land that was taken by the French, and then by the British. Then the area was settled by Scottish Highlanders and the Irish and all the rest. Farms and artisans begot small manufacturers, and eventually railroads, long coal barges plying the rivers, and massive factories that that supplied a rapidly expanding nation.

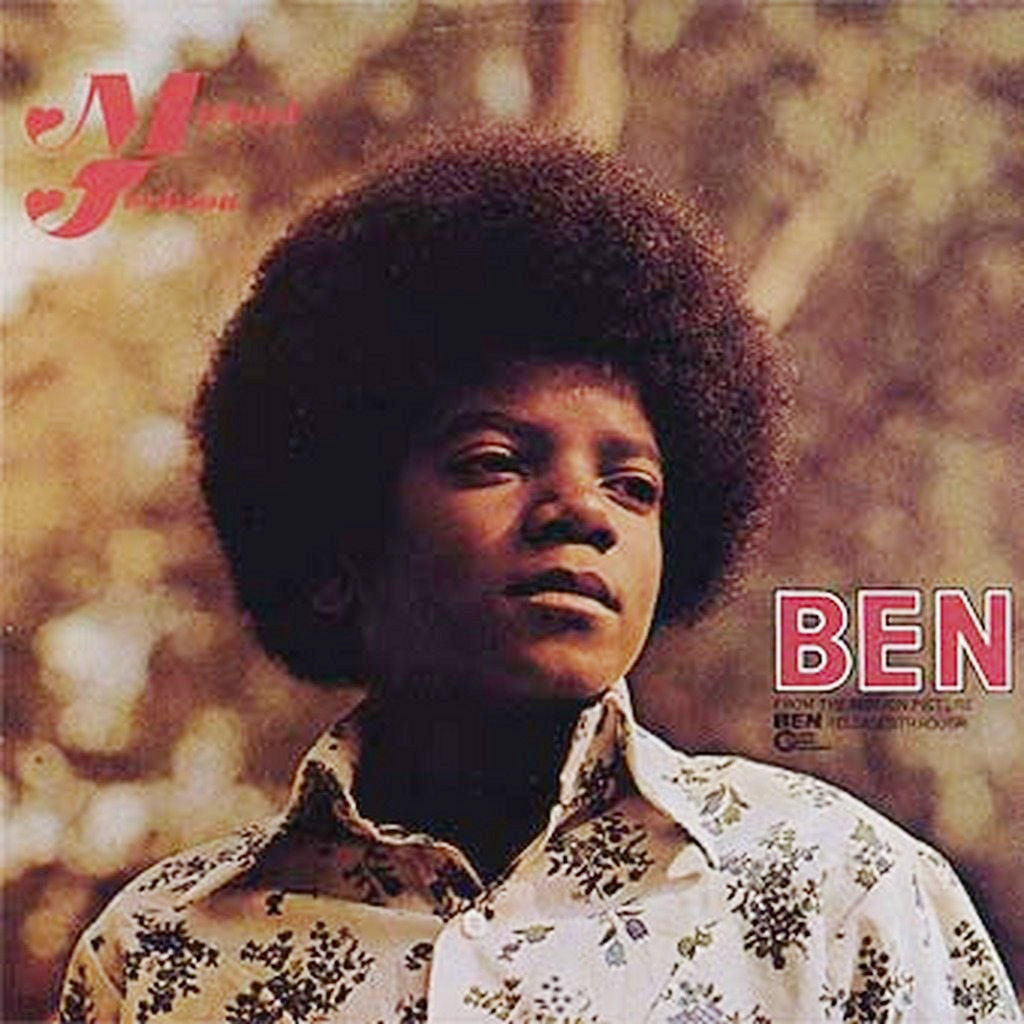

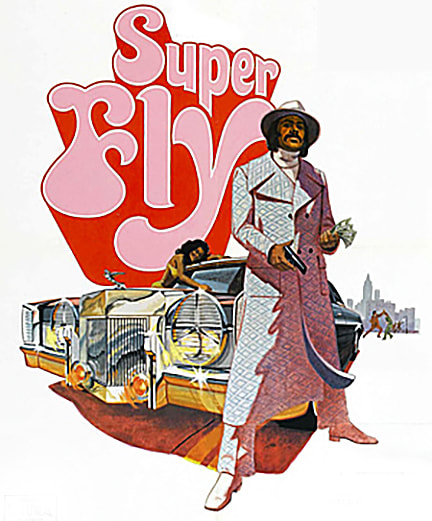

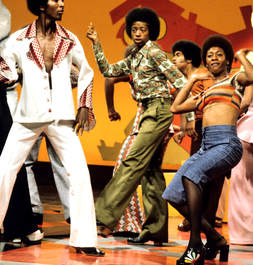

I want to think life back in my grandma’s time was a rich texture of mother tongues, simmering foods, raucous characters, big families, beer halls and polka music. Growing up in the 1970s, we caught the very tail end of that world, right before it gave way to the global, homogenized digital life we now know. So much has changed after a span of only about one lifetime. My great grandma’s peace and kindness was a stark contrast to grandma, Kathryn McCombs, who had a hard edge that tracked with the tough life she lead. There are some photographs of her and her friends having high times in Atlantic City, but the options had closed in on her, and she ended up alone in a little apartment.

She hailed from farm people up in Butler PA, lead by patriarch Uncle Bob, a corn and dairy farmer. At some point, a big coal deposit was discovered under his land and he became wealthy--although he never changed his down home farm ways. Mom and her sister LaVerne would visit the farm for long stretches in the summers, and she used to tell us stories about playing with cousin Lucille and her other cousins. There were unspoken secrets of Uncle Bob and his boys, doing shady things. Those secrets went to grandma’s grave, or someone’s. Mom sent us to the farm for a week once, which ended up being a bit awkward. We city kids were way out of our element. There were family reunions on the farm with big spreads of food laid out on picnic tables. They would roast a whole pig on a spit, using a geared down VW engine to turn it. The men in overalls and work boots would stand around admiring their contraption and sipping beer.  Allegheny County Jail. Architect Henry Hobson. Allegheny County Jail. Architect Henry Hobson.

Grandma married an Irish immigrant named Eddie McCombs. I don’t know anything about how they met or the brief life they had together. He abandoned the family when mom was four, and left grandma to mop floors and work as a hospital seamstress to raise two young daughters, my mom Ramona and her younger sister LaVerne. Eddie was another fuzzy, vague character in the family lore. Two things about Eddie. When we were up at one of the family reunions, his name came up and the older folks spoke in hushed tones about him, explaining that he was a strongman in the touring circus, and that he would bend steel bars. This lined up with what we did know: that he was 6’6”, a giant of a man in those days, and that he was in and out of jail for who knows what: fighting, drunkenness, crime? This was not uncommon among industrial age immigrants, dare I say the Irish especially. Grandma used to say with a tone of disgust how it would take six cops to physically overpower Eddie to bring him in. One time her bitterness toward Eddie surfaced. We were driving to a lunch downtown in the weeks before Christmas, to look at the window decorations in the three big department stores: Kaufmann’s, Gimbels and Hornes. We were passing the old stone gothic city jail that always seemed like some kind of haunted castle, and grandma blurted out “that’s where they took pappy!” Mom hushed her up pretty quick, but you could feel the defeat in grandma’s voice. Immigrant men faced prejudice and slim economic prospects in America. The work that did exist was a grinding vocational hell of long hours and unsafe conditions. All of this spawned a culture of violence and drinking, a macho existence that allowed no subtlety or empathy of the sort we see today. People and neighborhoods were split into factions along ethnic and racial lines. Outsiders would not be treated kindly. Slurs, brawls and an absolutist code of male pride were the norm. Walk through the old neighborhoods and you would count equally taverns and churches and graveyards. The juxtaposition of these places sums up the harshness of life. From the comfort of two generations removed, judging those times by our standards is a meaningless exercise.

When we’d go out to lunch with Grandma, she was the kind of person who took offense easily and had issues with the waitresses. She and mom were often in some kind of a dispute, likely grandma criticizing mom. Grandma used to drop N-bombs in conversation, each time corrected by mom. She would swipe glassware, tucking a coffee mug or a cocktail glass into her purse. One time, after a nice lunch at the Monroeville Mall we were all walking through the main atrium when grandma slipped and fell and a coffee mug from the restaurant skidded out of her purse. Mom was aghast and we three boys stood by watching another installment of a lifelong mother/daughter melodrama. As much as grandma was thin skinned and full of stern cautionary tales, she was sweet to us boys. Her face would light up when we arrived for a visit. On New Year’s Eve, she’d watch Guy Lombardo on the TV, the old time Canadian band leader. This was the most uncool programming imaginable for us kids to have to sit through. She and mom would pour themselves a little nip of Slivovitz, the clear plum brandy distilled throughout eastern Europe. When the Times Square countdown came on, grandma would weep quietly, which we never understood at the time. You can’t understand melancholy like that until a much later age.

Grandma’s sensibility came out of the great depression, which colored her worldview with a sense of scarcity and limited possibilities. She knew what it was like to not be able to afford things that we take for granted today. And she made sure we understood this. As an example of her simple, frugal ways, when she stayed with us, she would make us Baked Apples (Page XX) for dessert. This was just an apple cored and spread with some cinnamon and sugar and baked in the oven. Roasting brings out the natural sugars and it's a good treat that fills the house with a sweet aroma.

She was never far from an old world sort of superstition. We would overhear her talking with mom about “seeing red or blue.” She believed these visions enabled her to divine positive or negative future prospects. One of the old world remedies that remained was the dreaded mustard plaster. When you had a chest cold or cough, mom would mix Colman’s mustard powder with water and put the yellow paste on your chest for an indeterminate period of time. The thought was that this home remedy somehow stimulated "healing." For us kids, it was sort of a fear inspiring mystical thing, an additional indignity when you were sick.

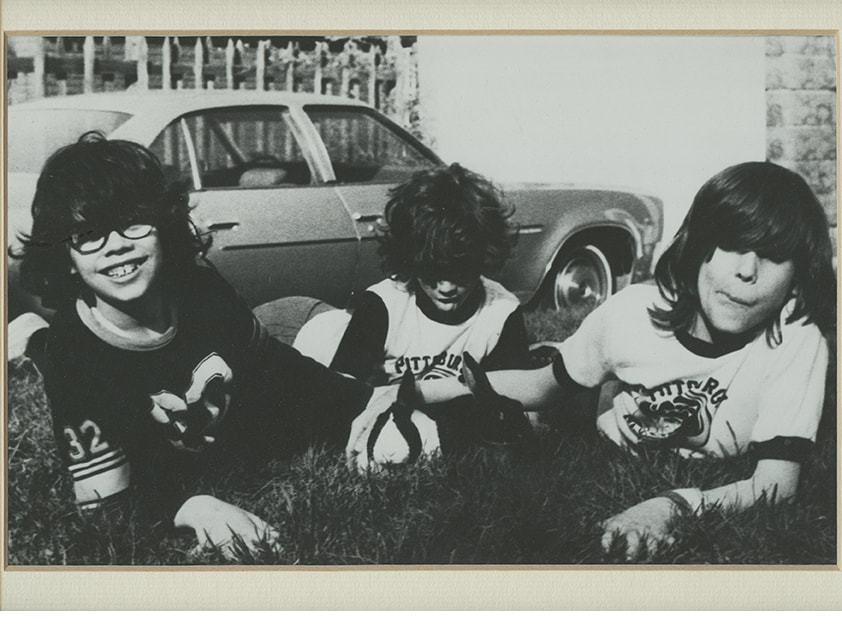

Grandma seemed otherworldly, like from the land of old people with her dentures, wig, beauty shop friends, and her beloved television preachers. Like many women of that time, she collected Green Stamps in little booklets, saving toward small appliances or other such luxuries. Her stories revolved around a cast of characters from the Braddock section of town and Wilkinsburg, where she lived. She did the best she could, and I think she would have been proud of how Andy and Mike and I turned out.

My mom, by her own account, was a brainy, shy, awkward kid. She was named Ramona after a popular movie and ballad of the late 1920s. She worked her way out of poverty, earning a full college scholarship with her smarts and sincerity. Grandma must have been a constant reminder to mom of where she came from, that maybe she was never able to completely pull herself up from the dark, old world of immigrants—grandma’s world. By her late thirties mom was divorced, and so also alone. Two women without men, struggling through a lifetime of insular dysfunction and love. Mom learned, like we all learn, that you can’t completely outrun the past.

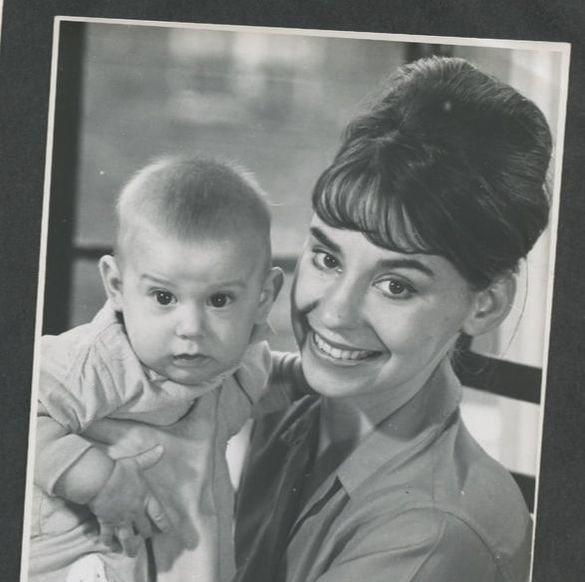

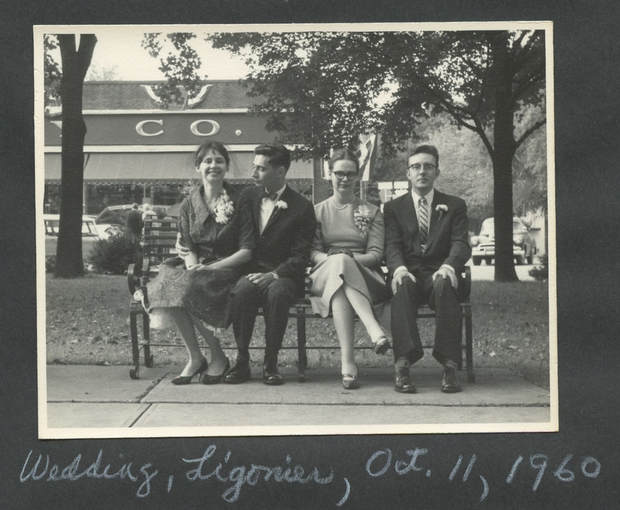

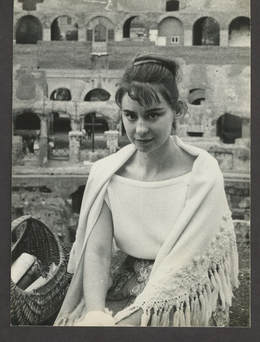

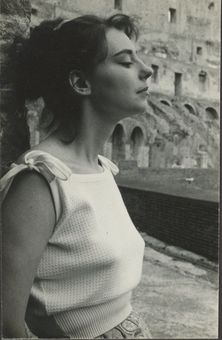

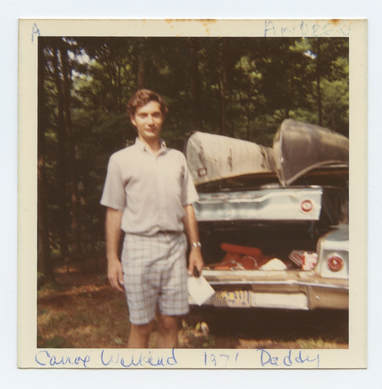

Mom was an impeccable student and editor of the school paper. She liked to tell the story of the one time when she strayed from the straight and narrow. Peter Lawford, a big movie star of the day, was scheduled to be in Pittsburgh. He was a dashing guy and eventual Kennedy brother-in-law. Mom played hooky from Wilkinsburg High School and went to try to interview him. She was successful, and was photographed with the movie star outside the William Penn Hotel on Grant Street. That photo made the Pittsburgh Press. The next day, her teacher interrogated her in front of the class as to her whereabouts the previous day. Mom went to Chatham College, a tony liberal arts institution, part of the intellectual blue blood Pittsburgh of the industrialists. She got the scholarship because one of her high school teachers recommended her. If not for that teacher, what would our family have been? Life turns on small kindnesses. I don’t know much about her college years, except that she was very proud of having gone to Chatham, and she would drive us through the campus periodically. She had a lifelong friend named Elsie from those years. When mom graduated she got a laboratory job at Westinghouse Research. She joined a hiking, skiing, sailing and outdoors club, the AYH (American Youth Hostel). That’s where she met dad, Armand, a chemist, also at Westinghouse. Dad grew up in Rhode Island and Brooklyn, and came to Pittsburgh by way of the Army and graduate school in Philadelphia, funded by the GI-Bill. It is interesting to note that mom and dad met in the late 1950s, almost exactly at the high water mark of American manufacturing power (1956, as measured by number of manufacturing jobs). They met in the American city that, more than any other, typified the industrial ethic. And they both worked for one of the industrial age titans. At mom’s memorial we actually got dad to talking about how they met. He has never been too communicative about the past. They were friends and riding together on a long trip to some AYH destination. As they were talking about other romantic prospects, the thought occurred to him, "what about this smart, pretty woman here in the car with me? It was nice to finally know that the genesis of our family was on some long car ride across Pennsylvania. Dad told one other story that day, from the early part of their relationship. Mom had a striking Audrey Hepburn look, a smart pixie heroine with brunette hair pulled into a bun on top of her head. They were in a taxi in New York City and got mobbed by people who thought she was Audrey Hepburn. When you look back at the photographs, she absolutely had that look. She radiated a light, an optimism, a beauty, and an empathy that’s hard for me to put into words. They got married in Ligonier PA, a pastoral town an hour east of Pittsburgh, with a main square and a gazebo. It was 1960. Ramona and Armand. I am transfixed by that black and white photo of them on their wedding day, so young and handsome, with another couple there in support. You can see the Woolworth’s 5 & 10 sign in the background. That image is frozen in time, left for me to ponder all these years later. But what about the food? Sadma (Page XX) is as this elemental Croatian dish in our family, something understood by mom and grandma that simply had to be made—it wasn’t even a question. It is a pot of sauerkraut with pork and short lengths of kalbasi bobbing around in the kraut. We kids didn’t like it at all. In fact it became elevated to a bogeyman type of concept in our world, nasty, pungent, foreign old world smell. Ironic that it is precisely these food memories that I cling to now, the further I get from those early years.

Stuffed Peppers (Page XX) is another iconic dish. Every Mediterranean culture has some variation. The Croatians mix ground beef, pork and veal with rice, spice, onion and garlic. They push this mixture into green bells, cover with tomato sauce, and sprinkle with a small handful of whole cloves, which give the red sauce a distinctive spicy flavor. You bake it in the oven in a cast iron pan and serve over boiled potatoes.

Grandma and mom also made Stuffed Cabbage (Page XX), a dish common to many eastern European cultures: Polish, Lithuanian, Hungarian, Czech, Ukrainian and Slovak. It is known variously as, halupkies, golabki, little pigeons, blind pigeons or pigs in the blanket. This dish uses a similar meat mixture to the peppers (without the rice), wrapped in a cabbage leaf, affixed with a toothpick, and then simmered in sauerkraut and tomato sauce. So good. In the early 1950s, mom worked for the USO in Germany, helping organize entertainment for our occupying troops. She lived in the picturesque university town of Heidelberg, where she learned German and had the opportunity to tour around Europe. She'd reminisce to us about the language tutor she hired, a strict battleaxe of a woman. Mom would make us Wiener Schnitzel (Page XX), and talk about her time in Germany. She’d use veal, and serve lemon beside the crispy cutlets. In subsequent years, we’ve subbed in pork and also chicken breasts. The dish is said to have originated in Vienna, Austria. There is also a bone-in Italian version called Cotoletta Milanese. These two variations trace back to two branches of the Habsburg empire, both of which claim credit for the dish. And it should be noted that wiener schnitzel is the sophisticated European forerunner to the current day kid meal of chicken tenders.

I didn’t realize until much later how mom’s time in Germany was a real coming of age time for her, and how important the experience was for a girl from a humble Wilkinsburg upbringing. One of the stories she told over the years involved the tense situation in Germany after the war. It highlighted how post-war geopolitics were not top-of-mind for young ladies on a European adventure. She and her fellow USO women traveled to and from West Berlin by train. Given that Berlin was surrounded by communist-controlled East Germany, the trains had to pass through East German train stations. They were instructed to pull their blinds closed at these station stops. Mom related with a confessional humor how she and her friends would open the blinds and flirt with the East German soldiers.

My brother Mike remembers another German dish that mom used to make, Sauerbraten (Page XX). This is one of the national dishes in Germany, originally made from horse meat. Today it is typically a tough roasting cut of beef, like rump or bottom round. The “sauer” part of name refers to how the meat is marinated in vinegar, wine and spices for at least three days, and up to 7-10 days. There are unsubstantiated stories that trace this dish back to Caesar or later to Charlemagne, where the vinegar was used to preserve the meat. If it’s done right, sauerbraten is tender and succulent. In the early 70s, mom would take us with her into a little deli in East Liberty called Hugo’s where she’d talk German with the people behind the counter. She would pick up bread, lunch meats, and strudel from this old world hole in the wall. And at school we’d be eating liverwurst and braunschweiger sandwiches while all the other kids were eating PB&J. Mom’s German experience must have rubbed off on us, because we’ve cooked a couple of other German staples over the years. There’s nothing better in the winter than Chicken and Dumplings (Page XX). In German these bread balls are called Knoedel or Kloesse. There’s a potato variation, called Kartoffelkloesse, and others with yeast and old bread. They get dropped in the stew in the last twenty minutes. The soft and light bready taste goes great with the rich, thickened stew. We also make Spaetzle (Page XX), the small noodle, cut in short irregular bits. There are all kinds of different devices for cutting the dough, or you can hand cut it right into the boiling water. We serve this with chicken stew or with Chicken Paprikash (Page XX), that we learned from our friend Elise here in Sacramento. My college roommate, Gerry, who grew up an army brat in Germany, taught me how to make Linzer Torte (Page XX). dark almond crust with lattice, dusted with powdered sugar. This has become a Christmas favorite in our household, translated more recently by my brother Andy’s wife Jennifer into Linzer Cookies.

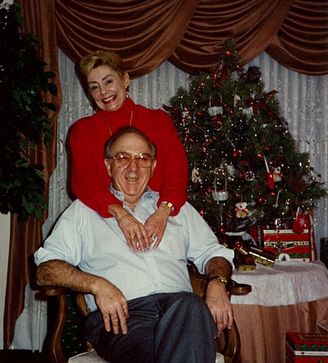

LaVerne and Ray had three kids, our cousins Ray (called Little Ray), Laura and Linda. They were older than my brothers and I, so we didn’t really hang out with them outside of holiday gatherings. As business boomed, Ray and LaVerne became wealthy and ran in hard partying country club circles. We would hear stories of lavish trips to Vegas and fishing in Florida, an audience with the Pope in Rome, and high stakes card and golf games at the club. They had boozy well heeled friends with nicknames—Nino, Bunny, Rocco, Nickie—all of them exotic in the ears of a middle class kid. Occasionally mom joked to us that Ray’s business “contacts” might include underworld figures, based on his Italian heritage and the construction related business. Ray was a smart businessman, and like a lot of Italian guys in Pittsburgh, very proud of his heritage. His Italian pride, like many others, manifested in a real macho personality. We’d go to their house for Christmas and it was exciting and high adrenaline to enter into that scene with all the large personalities, and the audience with Uncle Ray, the patriarch, on his recliner watching football or carrying on with his cronies, brothers and nephews. They had a big German Shepard, named Sargent, who Ray loved. Aunt LaVerne would joke that "he loved that dog more than her." After Christmas dinner, we'd take a walk with Uncle Ray and Sargent through the hilly streets of their neighborhood. Through the years he busted our chops a little, but was very kind to me and my brothers, the poor relations.

LaVerne would tell the story of how when she married into this big Italian family, all of the women convened and did an intervention of sorts in order to teach her the Italian recipes. She’d do this mock humorous rant about how the Croatian dishes had become overshadowed by the Italians. This sort of tribal knowledge transfer between women has been a thread throughout all time and all peoples—something as modest as women in the kitchen passing along recipes from memory, or from notes scribbled on scraps of paper. And at the same time this is such a significant part of culture and heritage.

Aunt LaVerne ended up mastering the Italian recipes. On the holidays, her kitchen was a hotbed of activity and delicious food. One of our favorites was Roasted Red Bell Peppers (Page XX), She’d bake or broil red bells until they blackened, then put them in a brown paper bag to steam, softening the burned skin so you could peel it off. After you cored the peppers, you’d be left with soft, tender, really sweet sections of pepper, cut longwise and dressed with olive oil, basil and a shake of balsamic vinegar. We’d eat them on bread. Another Italian dish that comes immediately to mind is Wedding Soup (Page XX). This is clear chicken broth with little meatballs and torn escarole floating in it. And also the tiniest of pasta, pastina, or also cavatelli or acini di pepe. The name is not, as I thought, because it is served at weddings. Rather, it traces back into Italian history, as a reference to the “marriage” between greens and broth.

Around Christmas there were always Pizzelle (Page XX), a currency flowing through town, made by aunts and grandmas (nonnas in Italian), and given away in little wax paper bundles. Pizzelle, like pizza derives from the Italian word for round. They are flat, round cookies about 4 inches across, with a subtle buttery anise taste, and thin, crunchy texture. They have elaborate snowflake and filigree patterns, imprinted by a pizzelle iron, similar to a hinged waffle iron.

Minutello’s in East Liberty was the fabled restaurant of our youth. We didn’t go out to restaurants nearly as often as we do today, so going out to dinner was a big deal. This was a joint in the basement of a residence hotel, a red sauce Italian place, connected to a dimly lit lounge. It was one of those places with the heavy aroma of good food and warmth, straw cloaked bottles of Chianti and martinis. There were drinkers and loud talkers in there, wise guys and gamblers and dames. The waitresses had bouffants and called you “hun” when they took your order. The Spaghetti with meat sauce was a hit with us kids. The sauce was rich and hearty, like the Sunday Gravy (Page XX) that was made in Italian kitchens all across town. The pizza was bubbled and blistered and served on silver pedestals. A legendary joint in our family. And they served this big Antipasto Salad (Page XX) loaded with meats, cheeses, peppers, black olives, pickled beets and carrots on an oval plate of iceberg. It had a basic red wine vinegar and olive oil dressing, but something about the balance and simplicity made it all work. And the bread, damn, that good simple Italian white bread. Years later we went back on visit from California, and found a faded relic, the same waitresses, now in their seventies, the food not nearly as good as the memory. Time marches on—Minutello’s!

When I was in college, grandma died. Uncle Ray paid six of his warehouse guys to carry the casket. He had funded grandma’s apartment for years, even though there always seemed to be issues between Grandma and Ray--likely because of grandma’s thin skin and her meddling in her daughters’ lives. At the funeral, things were unsettled due to some kind of grudge Grandma had against Ray.

Ray had come to see her in the hospital right before she died, to pay his respects and try to patch things up. The old bird was having none of it. On her deathbed she laid a curse on him, saying three times, “I curse thee, I curse thee, I curse thee.” He and his people weren’t too far removed from the old country—nobody was back then. So this curse really affected him. He called my mom several times to commiserate after Grandma’s death. He believed in the power of that curse and thought that negative things happened to him as a result. Here was a really successful businessman, haunted by a curse like that. That always struck me as a notable intersection of old and new worlds...and the power the old world still had.  Croatian Beef Stew Croatian Beef Stew

In Ray and LaVerne’s hard drinking country club life there were legendary fights between husband and wife, and always some sort of drama, owing to the likelihood that everyone was pretty deep into the drinks at gatherings and occasions. She gave as good as she took it.

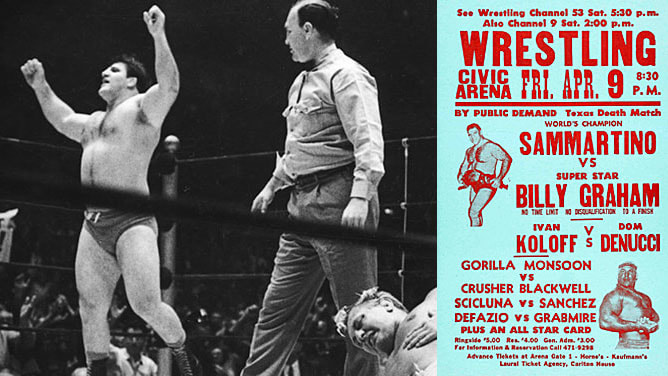

One time when I was home from college on a break, mom asked me to visit LaVerne. By that point, mom had been forced to move to Philly for a job after Gulf Oil got corporate raided by financier T. Boone Pickens. Ray and Laverne had split up, and LaVerne had moved into a high rise apartment. I went over there and she made Grandma’s Beef Stew (Page XX) for me. She was dying of cirrhosis, in and out of the hospital, her life had fallen apart, she was seen by everyone in the family as the cause of the split up, unable to control her alcoholism and erratic behavior. Her once magical personality was world weary. And here I show up, a fresh faced college kid. That day she just needed me to be there so she could cook for someone, and remember better times when she was cooking for her own kids. Even in that moment I understood the significance. It was a meal I’ll always remember, because it was near end of the line for her. And we had a nice time sharing that meal. This Croatian version of beef stew got its deep dark brown color by aggressively braising cubed beef three times in cast iron, and between each sear adding water or red wine to cool the temperature and concentrate a rich gravy. When the stew was simmering she told me we had to go on a little mission. She said we had to go get the big TV set from their house. She was always the outrageous one like that, with a devil-may-care attitude. I was worried about Uncle Ray being home and getting in the middle of a confrontation, but she assured me it would be OK. So we went up to the family home and snagged the TV set for her. Not quite breaking and entering, but definitely an oddball mission of mercy. One note on stews: although our family made beef stew, people made a lot of Oxtail Stew (Page XX) or soup back in the day. Mom talked about it periodically, although I can’t remember her serving it to us. She would talk about how the marrow made a rich broth, accompanied by potatoes, celery and carrots. As painful as the end was for Aunt LaVerne, I like to remember good times back in the earlier years. She would come over and all the rules went out the window. Our parents were strict about food and bedtime, but aunt LaVerne would override mom, decreeing that we would be able to stay up late and watch Chilly Billy’s Chiller Theater. This was a local campy creature feature program hosted by tuxedo-clad Bill Cardille, a former news anchorman. Or we’d watch the overwrought theatrics of Studio Wrestling, featuring Pittsburgh’s own Italian Superman Bruno Sammartino, tangling with large, unsavory men in tights—Gorilla Monsoon, Haystacks Calhoun, Captain Lou Albano, and others.

Aunt LaVerne just swept in and life became an adventure. And not only that, but we would go out to the Stop ‘n Go and get hoagies. My parents were health food nuts, ordering a lot of their foodstuffs from a mail order outfit called Walnut Acres. But on those nights, we would be drinking Cokes and wolfing down chips and hoagies. The Hoagie (Page XX) is a uniquely Pittsburgh name for a sub/grinder/hero sandwich: long Italian rolls split and stacked with meats and cheeses and lettuce, topped with a shake of Italian dressing. Sometimes they were made with meatballs and mozzarella, finished in the broiler. A Pittsburgh institution.

Dad hails from New England, but over the span of 60 years in the city, he has become a real Pittsburgher. A PhD. chemist, he has always been more of an intellectual guy, into the symphony and opera—not a sports crazy working guy like a lot of my friend’s dads were. After my parents split up, we would see him on the weekends. So he was a bit remote from the day-to-day of our growing up. He lived a bachelor sort of existence, a foreign universe compared to our mom’s household. Dad’s side of the family contributed less to my notion of the Rust Belt Kitchen. He wasn’t so locked into his heritage food. Dad is the kind of guy who never looked backwards, never dwelled on the past. We didn't really get a lot of his family stories. To this day, I have to dig those stories out of him.

His family of Polish Jews had to sell their share of a Fall River, Massachusetts textile factory when his father became ill. His older brother, Uncle Gil, was also a chemist, the academic star of the family. His claim to fame was that he worked on the Manhattan Project, and was responsible for a key breakthrough that expedited the race to complete the atomic bomb. Dad's sister, Aunt Sally, ended up in a low-down bohemian apartment in the Manhattan financial district after presumably freewheeling times in the 1960s Greenwich Village arts scene. I turned up drunk at her apartment door in my first year out of college, not having seeing her since I was a kid. I was working in Newark, hanging out in Manhattan a few nights a week. I somehow had remembered the place on Pearl Street. I found her to be weathered but full of wisdom and humanity, sharing with her young nephew copies of her handmade books, and talking about her volunteer work caring for homeless people out of the Trinity Episcopal Church at Broadway and Wall Street. I made a handful of visits that year. She was an artsy idealist to the end.

Dad worked at Westinghouse for 35 years, the company founded by innovator George Westinghouse, whose alternating current system of electricity prevailed over Thomas Edison's direct current. Dad referred to the sprawling high security research park where he worked as "the lab." He took us there on weekends sometimes when he had to check on an experiment. The place had a modernist science fiction feel to it with the clean white buildings, vast lawns, the room-sized scientific apparatus, and special sealed experiment chambers. In the prime of his career in the 60s and early 70s, he worked on defense contracts that involved uranium and atomic energy. He and his colleagues were awarded many patents for this work, and he made trips out to Utah and California related to the mining of uranium. He had a professorial look with his trademark bow tie and the old leather brief case he toted around.

As a man of science, a practical, rational guy, dad has never been a believer or a practicing Jew. He didn’t pass that tradition along to us. But some of the heritage food did get carried on. We loved his potato pancakes, Latkes (Page XX). The trick is to wring out as much liquid from the grated potatoes as you can. So dad would be standing over the sink wringing the hell out of a dish towel full of potatoes. Then you mix in minced onions, egg and a little flour and fry up on a griddle. Top with applesauce and sour cream. If you do it right, the latkes are golden brown and crisp.

According to mom, dad’s mother, who we never knew, made a killer Beef Brisket Roast (Page XX). Brisket is a tougher cut of meat that you braise and stew on low heat with carrots and potatoes. When I asked dad, he mentioned the economics of the cut of meat, and how liver was another low cost meat that had to be cooked slow and easy so it didn’t get tough. He said they gave away liver when he was growing up. Actually our neighbor in Highland Park, Mrs. Rothman, came to wear the brisket crown. Mom got her recipe and it became a family favorite. The city of Pittsburgh was truly an industrial age eastern European melting pot of Ukraine’s, Poles, Serbs, Croatians and Russians—Jewish families from all of these traditions. The Squirrel Hill neighborhood is the center of Jewish culture. Leading the long list of Hebrew favorites are Blintzes (Page XX), Matzoh Ball Soup (Page XX), kosher pickles and gefilte fish.

On the weekends we’d drive around town in dad’s yellow Toyota Corolla station wagon, bound for a regular set of outings and activities: flying in his small airplane, canoeing, camping, ice skating at the Monroeville Mall, and also going to the Heidelberg flea market. This is where they would serve Perogies (Page XX), one of the defining Pittsburgh dishes. This polish mainstay is a dough dumpling stuffed with cheese, potato and sauerkraut. It’s boiled and topped with sour cream. After boiling they are often browned in a skillet with butter and mushrooms.

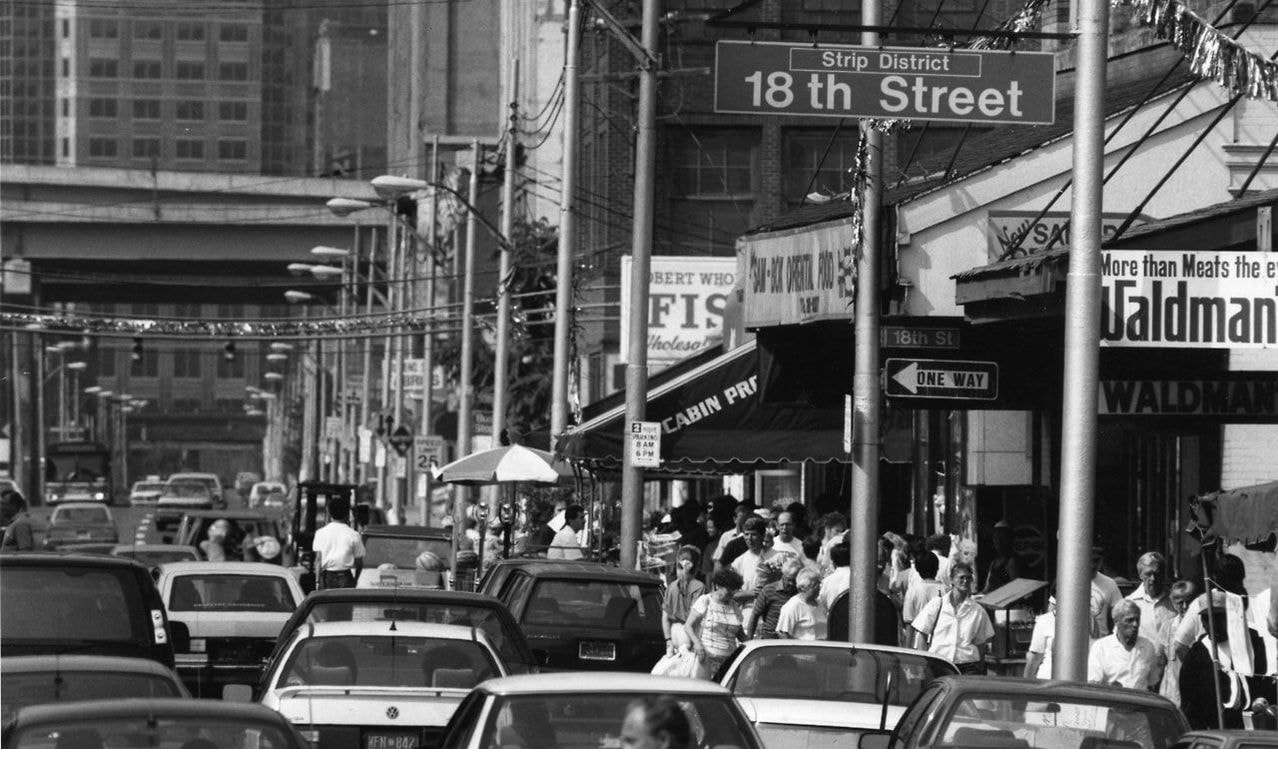

I have early memories of dad making wine in the basement. Over the years he continued this hobby in the various apartments and houses he moved through. As a chemist, he enjoyed the process: sourcing the grapes up near Lake Erie, the measurement of the sugars, the laboratory-looking bubbler that allowed the gas to release from a 5-gallon glass carboy, the finer points around aging and bottling. To this day, the musky, earthy aroma of wine fermentation is a strong trigger for those early memories. One of dad’s favorite things is to cruise the Strip District, the wholesale produce loading docks section of downtown that in the 1980s was evolving into a retail area. We’d buy olives, cheeses and bread, tearing at the bread as we strolled with the crowds on Penn Avenue. The Pennsylvania Macaroni Company was at the center of it, a lively wholesale Italian deli of endless blocks of cheese, meats and canned items. And further down the street was Wholey’s, vast and smelly fish market, a Mecca for dad, who loves fish and mussels and clams. Most often he’d poach or broil flounder, white fish or scrod. He ate a healthy diet and jogged way before it was cool. One his defining things was jogging around the Highland Park reservoir, with us three boys tagging along behind. And later, in our teenage years, he was proud when we would out-pace him on those runs. Like the Pennsylvania Macaroni Company, there are a handful of other food joints and companies that are local institutions, and have become generational touchstones of the Pittsburgh food experience. The Strip District is the home to a little joint called Primanti Brothers, and their famous Primanti’s Sandwich (Page XX). This spot dates back to the 1930s, way before the Strip went retail, when it was strictly a loading dock for produce and other wholesale commodities. Primantis wouldn’t open until late at night, and then they’d stay open all night serving the long haul truckers and warehouse guys. They devised this sandwich that’s a whole meal right between two thick slices of Italian bread: meat, cheese, french fries and coleslaw, stacked high! It’s a thing to behold. The legend has it that this all-in-one sando was a one-handed meal that allowed the truckers to steer and eat at the same time. Who knows if that’s accurate?

Sometime in the 1980s, college kids figured out Primanti’s was open after the bars had closed. So it became a big late night scene on the weekends, with wasted kids spilling out into the little alley in front, crushing cheese steaks and Iron City Beers. Somehow, Primanti’s used to serve beer after the statewide last call. You got the sense that in the Strip, things ran according to their own set of rules. In recent decades the restaurant has opened several suburban satellite locations, and has become a real Pittsburgh trademark.

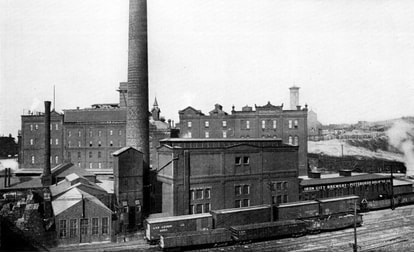

Iron City Beer has been the go-to local lager dating back to its founding in by a young German immigrant in 1861. For a time it was one of the largest and most advanced brewery operations in the country. It was brewed in an old red brick factory at the foot of Polish Hill, up until the beer industry consolidation of the late twentieth century. Today, after a bankruptcy and several ownership changes, the brand is now produced at another location. When you order one, you just use the shorthand “Gimme an Iron.” Most neighborhood dad’s had a case of Iron returnable bottles in the basement at any given time. It was an era where a guy was loyal to the local brand, before today's endless consumer choice and the following of short term trends. For the record, Iron is a fairly low-grade watery swill. But hey, its the hometown brew! Because of Pennsylvania’s blue laws, you’d have to get your case of beer from a beer distributor, not the supermarket. Blue Laws had religious origins maybe an artifact all the way back to Puritan thinking. Back in the high school days we might have gone on a few runs to beer distributors, playing out various schemes to get served underage.

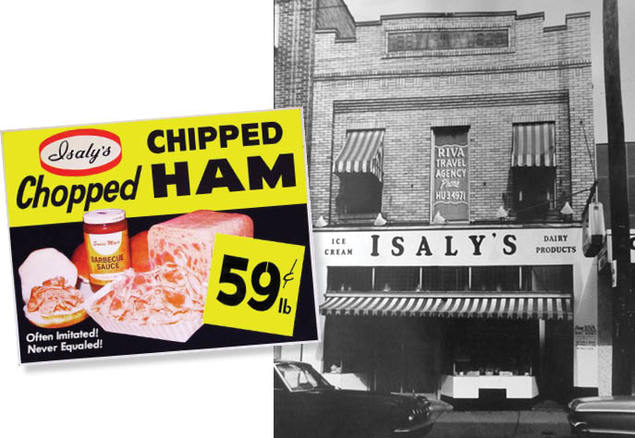

Another notable local institution is the now defunct chain of deli/soda fountains called Isleys, that at one time spanned eastern Ohio and Western Pennsylvania. This ice cream, cheese and sandwich purveyor was really big when mom was growing up, with locations in neighborhoods across the city. She would take us to a few of the fading locations that remained and relive the old days. They had two claims to fame. One was a summer favorite, the Klondike Bar, a palm sized block of vanilla ice cream dipped in chocolate and wrapped in silver foil with a polar bear graphic printed on it. The other thing was the Chip Chopped Ham Sandwich (Page XX), essentially a ham sandwich on sliced white bread. The thing that made it great was that the ham was sliced or “chipped” into razor thin pieces. Something about the texture of the meat, usually with some mayo, made for an amazing taste. Never mind that it was chipped out of a square looking ham loaf made from who knows what nasty parts and pieces. Read more about Isaly's. I would be remiss to not mention the Clark Bar. Through much of the twentieth century, the Clark Bar was one of the most popular candy bars in the nation and one of Pittsburgh's famous food brands. It was a crunchy peanut butter core covered in milk chocolate. The Northside factory featured a large neon sign that was a downtown area landmark. By the 1980s, the Clark Bar brand began to fade, unable to compete with newer candy options and increased competition. Read the story here. Pittsburgh is the quintessential working class town, imbued with a strong sense of blue collar pride that you readily notice of when you are there. It’s hard to pinpoint, but there’s an unvarnished quality to the people, most apparent in the accent, that distinctive raw, nasal raspy sound. Nothing shows off the accent better than the pejorative “jag off”, especially dropping it paired with an F-bomb: “Hey you fuckin’ jag off, that’s my sister.” The other trademark colloquialism spoken with the same rasp is “yinz,” meaning “you all,” as in “What time yinz goin’ dawn-tawn for the game?”

Art Rooney, "The Chief." Art Rooney, "The Chief."

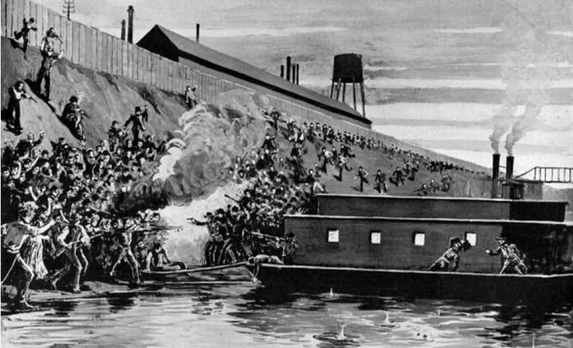

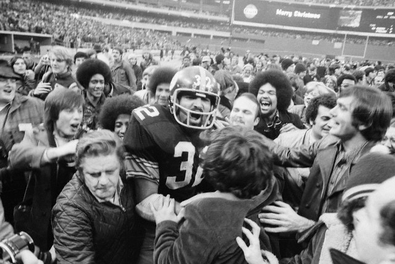

This hard quality came down the line from early times when Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia comprised the country’s hillbilly frontier territory of independent farmers, and then later, miners and factory workers. Pittsburgh was the location of the 1791 Whisky Rebellion, the first instance in U.S. history where working folks tried to push back against the financial class. Later, in 1892, the Homestead section of town was the scene of a seminal labor fight, when a rag tag band of workers went on strike to protest a twenty percent wage cut. They took up arms against strikebreakers and thugs hired by Andrew Carnegie and William Clay Frick. The strike was eventually broken by 8,000 state militia who marched into Homestead and reestablished order. Nothing encapsulates Pittsburgh working pride more than football and hockey. They were real blood sports back in the 70s—violent, tribal and unforgiving. The Penguins, called the Pens, played in the domed Civic Arena, known as the Igloo. Hockey was popular, especially because of the vicious on-ice brawls that were common in that era. But in Pittsburgh, football is king--Steelers football especially. You know you are talking with a real homegrown Steeler fan if you hear that raspy accent that turns steelers into “stillers.” The city of Pittsburgh suffered through decades of really bad Steeler teams all the way back to the early 1930s when the team was founded by a northside Irishman named Art Rooney. He was raised above his dad’s saloon, and was something of a neighborhood fixer and gambler. He paid the franchise fee for the team with race track winnings. Three years later, he had a legendary 3-day winning streak at Yonkers and Saratoga in New York, hitting a big parlay and five longshots among 11 straight winners. It’s a streak that remains one of the greatest horse betting feats of all time. The hundreds of thousands of dollars he cleared financed the team through many subsequent lean years. Rooney, affectionately known as “the Chief,” was an iconic, beloved character with his trademark cigar and shock of white hair. Late in his life, his faith in the chronically under performing team was finally rewarded. Uncle Ray was big Steelers fan. Every so often he would take us to a game, and it was like Christmas morning in our world. I can’t emphasize enough how big a deal this was. We had no means to go to these games. They were always sold out and there was no such thing as StubHub. The anticipation was unbearable as we'd pile into his big Cadillac, stop at a neighborhood deli for hoagies, then he'd steer through the ratty streets of the North Side, past the hustlers and ticket scalpers and winos, toward the concrete Mecca of Three Rivers Stadium. His season tickets were in the second to last row at the very top of the circular colossus. He knew all the folks sitting around him. There were thermoses of cocoa passed around and, of course, people were swilling Iron City beer. There were those big winter coats with the fur lined hoods. We sat through some really cold games watching the black and gold Steelers on the artificial turf way down below. Then one year, as his business thrived, Ray moved from those seats to a luxury suite with a kitchen in it and a whole deluxe furnished setup. That move tracked with the ascendance of the team into their dynasty years of the 1970s. The singular event that birthed the Steeler dynasty was the Immaculate Reception in ‘72, an improbable last second turn of events against the Raiders in the playoffs. It was so named because of such a lucky carom of the football people thought it could only have been divine intervention. The exact spot where it happened is marked in the parking lot next to the new stadium. The hero of that play was Franco Harris. Franco is a mild mannered African American dude with a beard and big afro. But he is also half Italian. So the the paesanos in the Italian community, the big old ball buster dagos who sometimes slurred blacks as “eggplants” embraced this guy. They formed Franco’s Italian Army, complete with combat helmets and tri-color Italian flags. They’d hold up this iconic sign in the crowd that read “Run Paesano Run.” In a town still self segregated by race and ethnicity, Franco’s Italian Army was a novel cross ethnic thing.  Myron Cope Myron Cope

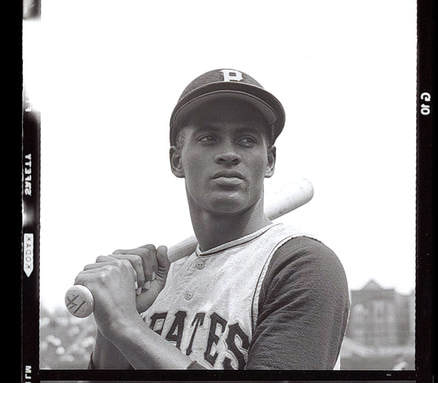

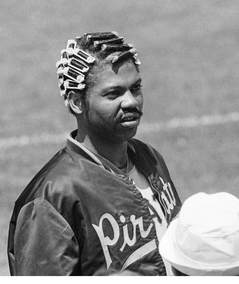

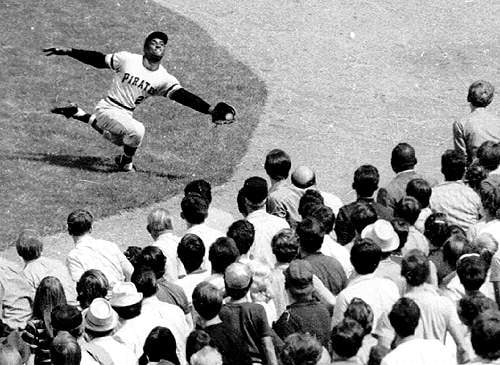

Historical footnote: Broadcaster Myron Cope is credited with naming the Immaculate Reception. He also invented the now ubiquitous Terrible Towel. Cope was an excitable little guy in a loud checkered sport coat, with a hard edged Pittsburgh accent, a distinctive nasal vocal delivery not unlike a local version of Howard Cosell. Today, watch any Steeler home game and you’ll see a stadium full of these yellow rally towels waving madly. Despite Uncle Ray’s improved seating fortunes at the stadium, I like to remember him way up in the upper deck, living and dying with his team, back when Terry Bradshaw was battling former Notre Dame quarterback Terry Hanratty for the starting job, and Mean Joe Green was just establishing the Steel Curtain, what would become the most dominant defense in the history of the sport. On the day of the first Steelers Super Bowl, Mom cooked grandma’s recipe for meatloaf, a fairly typical recipe made from a third each ground beef, pork and veal, with diced pepper, onion and celery. She’d coat the outside of the loaf with Heinz Chili Sauce, a ketchup-like condiment, but more spicy. They beat the Vikings that day, after which the team played in three more Super Bowls over the next five years. Each time, we boys insisted that mom make that same meatloaf. And they won all three. We concluded that Mom’s Super Bowl Meatloaf (Page XX) was undefeated at 4-0! In the mid-90s we tried to recreate mom’s magic out in California, but the Steelers (and our meatloaf) were defeated by the Cowboys. Like all kids across the city, we idolized the great Pirates right fielder Roberto Clemente. He grew up in the poor sugar cane fields of Puerto Rico and was one of the early Latino players to break into the big leagues back in the mid 1950s. He was a five-tool player who routinely cut down runners with his cannon arm and made impossible catches at the wall. Any mention of the Pirates of our youth begins with him.

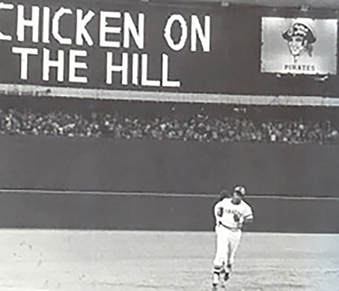

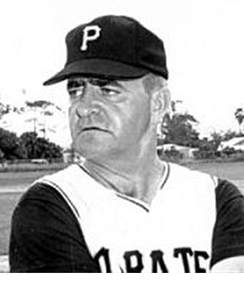

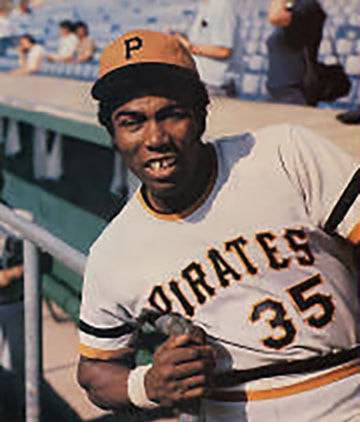

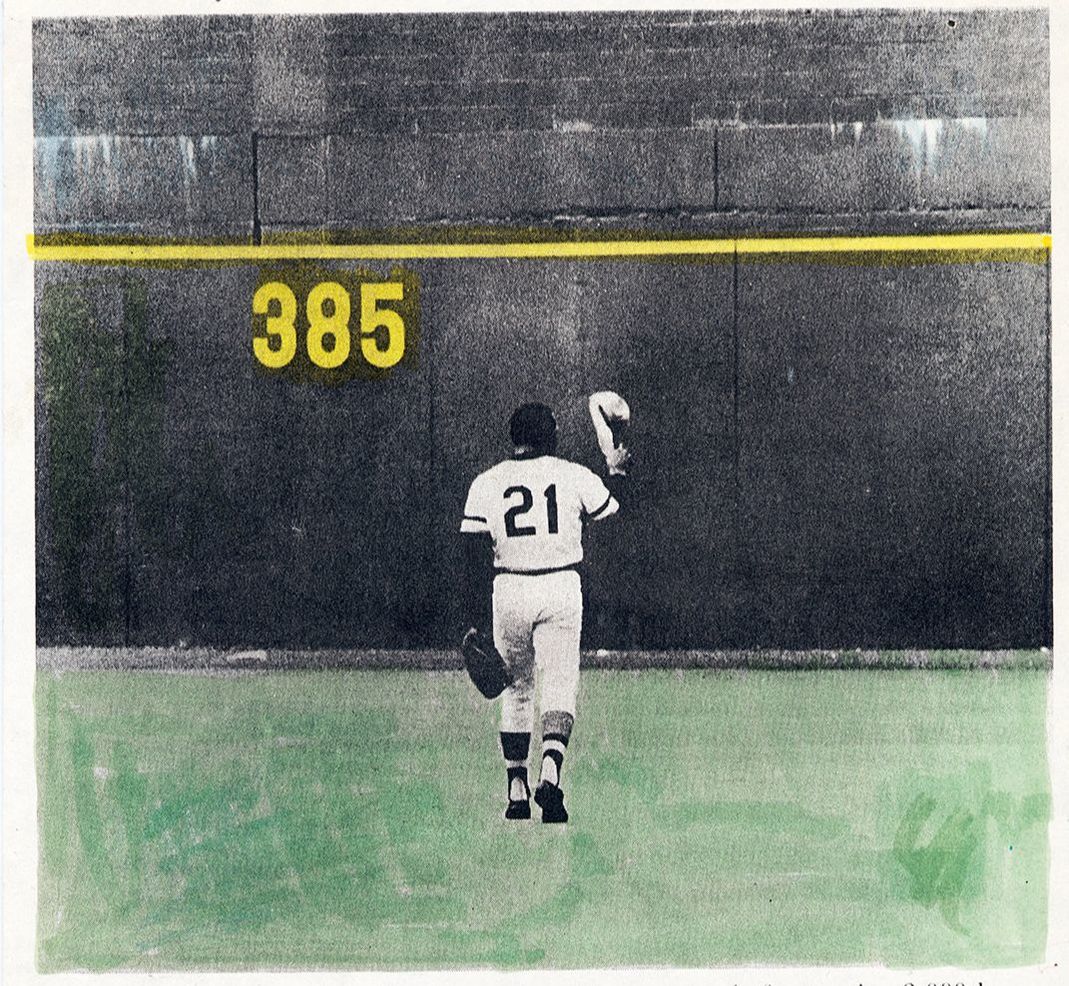

The Pirates are affectionately known as the Bucs or Buccos, short for buccaneers. We listened to Bob Prince, “The Gunner,” on KDKA radio. His gravelly voiced, homespun narrative was the soundtrack to many a summer evening, peppered with so many great nicknames and signature calls. Games were only occasionally televised, so there was always a transistor radio nearby with the staticy play-by-play going in the background. One famous Prince call was Chicken on the Hill with Will (Page XX). According to legend, it originated as a spontaneous promise he made on the air, that if Willie Stargell homered everyone inside Stargell’s fried chicken joint would get free chicken. The restaurant was in the Hill District, a neighborhood of row houses that was the center of black culture in the city. It had been home to the renowned jazz joint, the Crawford Club, a regular stop for luminaries including Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Lena Horne, John Coltrane and Charles Mingus. By the 70s the Hill was plagued with crime, junkies and boarded up buildings. We kids feared Hill District in the manner of urban legend, and never dared go through it. Willie Stargell did homer that night, and the restaurant was mobbed. It remains unclear who paid the bill or if the offer continued—but the saying lived on as Prince’s home run call whenever Willie went deep. Price told long, rambling stories, including episodes and hijinks with the team on the road. That Pirates team reflected the funky, soulful vibe of the early 70s. It was a team full of memorable personalities: the magnanimous, power-hitting Stargell; the ever smiling Panamanian catcher Manny Sanguillén; manager Danny Murtaugh, an old Irish cogger; and militant, corn row wearing Dock Ellis. Ellis owns one of the most bizarre feats in the history of the game, having thrown a no-hitter while tripping on acid. He was an outspoken critic of racism he saw that persisted in the game of baseball. This didn't sit well with the establishment powers within the sport. A little known side note is that when Ellis was under attack in the press for his combative attitude, the immortal Jackie Robinson himself sent him a personal letter of support and advice. In 71, the team had the distinction of fielding the first all-black starting lineup in Majors history.  Clemente Clemente

Clemente was the soft spoken leader of this swaggering ball club that won the World Series in 71. He had a haunted elegance and a quiet intensity. Teammates and opponents alike sensed they were in the presence of greatness. Others misread the distant persona as arrogance. The elaborate ritual of Clemente taking the batter’s box was mimicked in sandlots and wiffle ball games all over town: the handful of dirt, the neck and back gyrations, the deliberate sequence of precise adjustments. And then that off-balance reaching swing was so wrong according to hitting orthodoxy, but so effective and memorable. He played with a reckless abandon. His compact body had a certain indescribable quality to it, flailing, but with a self contained sort of grace and nobility. By the time I saw him play in person, in 1972, his legend was well established, and he had won over the tough blue collar town. The neighborhood paesanos in the first base grandstand that night sat in awe of Clemente. All evening we watched number 21 pad across the artificial turf under the lights. He seemed misplaced in the modernist concrete of Three Rivers Stadium, occupying his lonesome spot in the faded green reaches of right field. It would be his final season. Clemente was killed while on a humanitarian mission to earthquake-stricken Nicaragua. The old DC-9 plane he overloaded with food and supplies crashed into the sea right after take off from San Juan Puerto Rico. His tragic death crushed the city, and people all over the world. He left an indelible mark on a whole generation, and remains to this day a sacred icon in the Pittsburgh mythology.

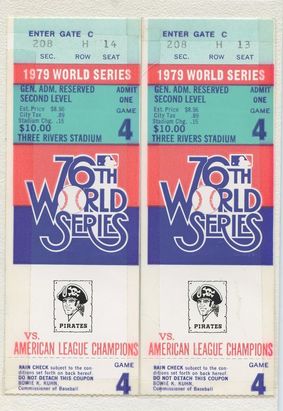

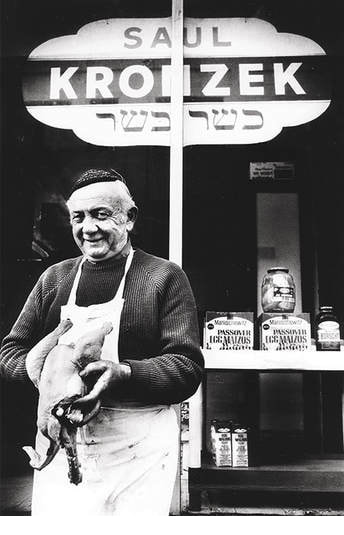

We were entranced by baseball and the Pirates throughout the 70s, culminating in the 1979 championship season. I spent that summer riding the bus down to the stadium, buying $2.50 upper deck outfield seats, but then sneaking into box seats, and exploring the bowels and catacombs of the stadium with bands of other stray, delinquent kids. That year is remembered as big-hearted Willie Stargell’s magnum opus, and also for the team’s stovepipe vintage caps—an oddity in the annals of Major League fashion. When they made it to the World Series I waited in line and purchased, with my meager teenage funds, two tickets to game 4 for me and my dad. He wasn’t a ball fan, but over the years he was a good sport about sitting through games and playing catch in the park. The Pirates lost that game, leaving the series at 3-1 in favor of Baltimore. An impossible predicament. We walked down long concrete ramps and out of the stadium with the deflated crowd. Owing to my dad’s extreme frugality we had parked in a North Side neighborhood, blocks and blocks from the stadium, up past the old Clark Bar candy factory. That was a solemn march. On the drive home I teared up, one of the very few times any kind of emotion came into our stoic relationship. My dad said a few sympathetic things but mostly stayed quiet. Somehow that car ride home is one of the nice memories I have of me and my dad. The deep despair of Game 4 set up an unlikely comeback. The Pirates, rallying around the disco song ‘We Are Family,’ ended up winning three straight to take the Series. And in Baltimore some other kid was crying.  Saul Kronzek and his family fled anti-Semitism in Poland and came to Pittsburgh in 1927. Though he had studied to be a rabbi, Saul took a job as an apprentice butcher to help support the family. Saul Kronzek and his family fled anti-Semitism in Poland and came to Pittsburgh in 1927. Though he had studied to be a rabbi, Saul took a job as an apprentice butcher to help support the family.

When we were growing up we caught the very end of home milk delivery, neighborhood butchers and greengrocers. These service providers were a fixture across the land for decades, but like many others, were swallowed up by the rise of the supermarket. Although today there are lots of specialty markets, we mostly end up at the Safeways and the Krogers to hunt and gather at the terminus of rich global supply chains. We willingly trade freshness and local charm for lower prices, predictability and produce that never goes out of season. This book itself is a preservation effort in the face of a growing monoculture that seems to threaten local and unique things.

Just a few decades removed, how foreign it seems that someone would put fresh bottles of milk in a metal box on your porch every couple days and take away the empties? Or that you’d have a close personal relationship with the guys down the street butchering up hogs and sides of beef. When my brothers and I were still pretty young, there was a kosher butcher mom went to called Kronzek’s, on Bryant Street in Highland Park. Mom would walk in with us three boys in tow, and the butchers would kibitz and dote on us and hand out slices of salami. I was captivated by the medieval tableau of meat dangling from hooks in the window, the strange fraternity of old guys in bloody aprons, and the way mom communicated with them in the language of weight and body parts. All three women in the family made this incredible Chicken Noodle Soup (Page XX), from grandma’s old recipe, presumably handed down from her mom. It had a clear broth from scratch, egg noodles, a little carrot and celery, and hit with some parsley at the end. Pretty standard recipe as chicken noodle soup goes. Mom used to say the secret was to get chicken backs from the butcher and chop those up, exposing the marrow inside, and boil them to make the broth. I’m not even sure chicken backs are sold separately any more. This was one of many frugal things depression era folks did to save money—buy the discarded parts to use for soup. And when you got sick, mom would make a big pot of chicken noodle soup. It was better medicine and comfort by far than anything out of a pharmaceutical bottle.

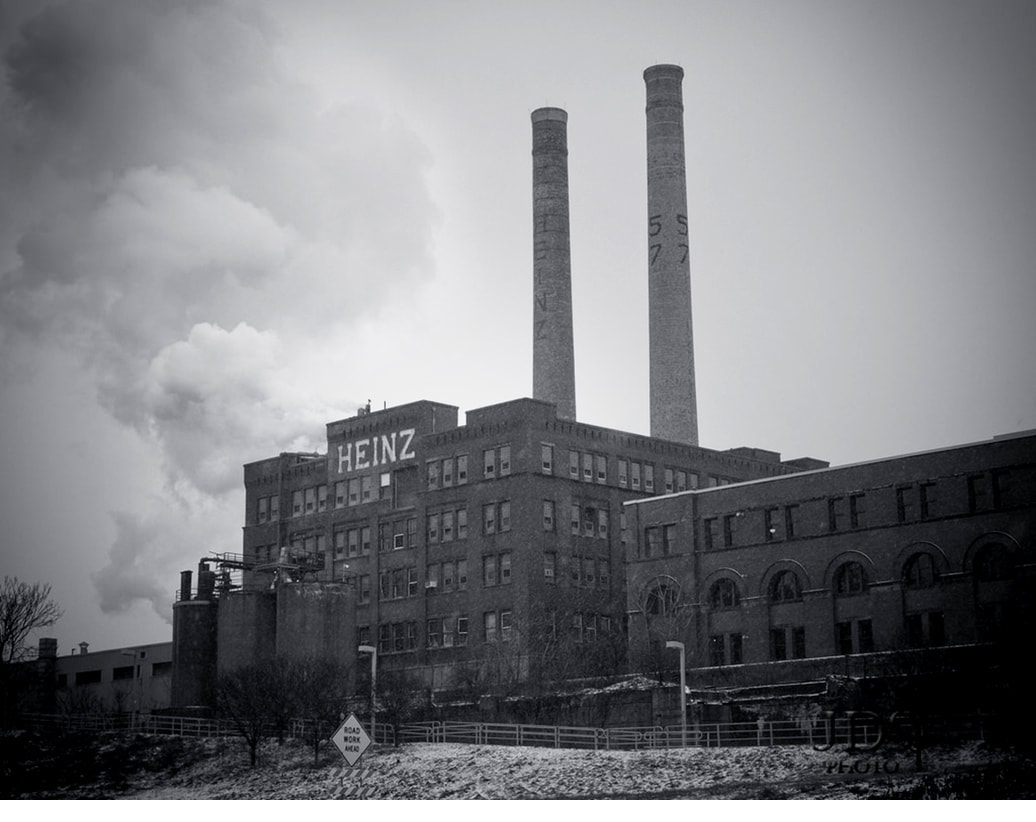

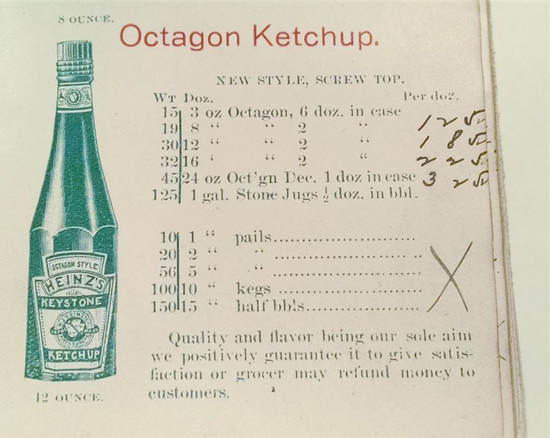

No story about Pittsburgh food is complete without mention of H.J. Heinz, a company that dates back to the 1850s when an enterprising 8-year-old kid of Bavarian descent, Henry Heinz, started peddling his mom’s garden vegetables to the people in his Sharpsburg neighborhood. By age 15, he was bottling Horseradish (Page XX) in volume in the basement. He grew this little operation quickly by scaling up and mechanizing the traditional home canning process. Pickles, Sauerkraut (Page XX) and vinegar followed. They were delivered to local grocers by horse-drawn wagons. He adopted the slogan “57 Varieties” and eventually grew into a global food processing conglomerate that sells over 200 brands across six continents. The flagship products are pickles and the ubiquitous red bottles of ketchup (see Henry Heinz's original recipe, called Octagon Ketchup Page XX ). The Heinz factory, with towering brick smokestacks, dominates the north side of town. Elementary schools across the city tour the plant, where each kid receives a little Heinz pickle pin.

Aunt LaVerne would put up her own prized Sour Dill Pickles (Page XX), really tangy and crisp. Our cousins and we would power through a big half gallon jar in one sitting, garlic-rich, and with a little heat in the aftertaste. Today I make non-fermented Refrigerator Dill Pickles (Page XX), but have not cracked the code on the fermented variety, requiring a precise gestation period and attention to temperature and sterilization. There was something about a guy LaVerne knew at a local farmer’s market, a greengrocer, who would tip her off on when the ripe pickling cucumbers would be coming to market. We all waited with anticipation for his seasonal intelligence report.

Among the variety of salads mom, LaVerne and grandma made, three became mainstays, each tossedwith a simple vegetable oil and white vinegar dressing, using sugar and salt to create a sweet and sour balance. And each included a bit of onion. In the food world today where chefs employ all sorts of elaborate, flavor-intensive ingredients, it’s all the more notable in my mind that these salads have a simplicity that allows the vegetable flavors to come through.

The Endive, Dandelion & Escarole Salad (Page XX) is made with some combination of those bitter greens. It has tiny cubes of boiled potato in it. The jagged leaves of the dandelion and endive have a strong flavor, something of an acquired taste. Dandelion has all but disappeared from the American table, but was once quite common in this country and in Europe. Due to its hearty nature, sometimes you let these greens sit in the dressing a little longer to soften up. Red Cabbage Slaw (Page XX), has this color that is so deep and dark red, it seems otherworldly. It’s gotta be cut thin and then should sit for a while after being dressed to soften up and fuse. For the Sweet & Sour Cucumber Salad (Page XX), you peel the cucs and slice them thinly. And then dress, adding some onion slices, also as thin as possible. Simple as that. As with the other salads, this one also gets better as it wilts and the cucumber discs break down and release some of their liquid into the dressing.

There was a hand made element to the way these salads were put together that’s different from merely opening a bag of lettuce and a bottle of dressing. After washing the lettuce, grandma would put it in a metal wire basket and go out on the porch and swing it in a windmill motion and the water would shed off the leaves from the centrifugal force. She'd cut the cabbage with a knife, not a mandolin. It was this practiced technique where you’d have to just shave the face of the cabbage to get a really thin cut—just sort of let the knife glide down and catch a bit of the cabbage. Looks easy until you try it.

Mom and grandma would shake the unmeasured dressing ingredients directly into the bowl. And then they would toss the salads with their hands—no spoons or tongs. This kind of hand mixing reminds me of how Roy Choi talks about washing rice. He’s the LA guy who started a popular Korean taco food truck operation. In his Korean tradition you’d rinse the rice with your hands three or four times. And he explains there would be this little spiritual moment of time where you’d just let yourself go and feel the texture of the food and lose yourself in the process. Sure, it’s a little touchy-feely, but I think there’s something there, some point of connection with the hand mixing. And maybe when your family eats the food, they can taste that love and care. For a few years in the early 70s we lived in a big three story brick house on Hampton Street, just off Negley Avenue in Highland Park. The families on our block spanned from professionals to working class, of many ethnicities: Italians, Jews, middle easterners, Poles and anglos. All of us kids played together and ran in a pack of over 15 or 20 kids. That time period really was a heyday for us three boys—being on that block with that gang of kids, living in the big house, our parents still together. What I remember are the long aimless summer days, running around the neighborhood, or riding our banana seat/sissy bar bikes; the all-day games of wiffle ball; the outings to Highland Park where we’d swim in the big public pool full of kids from all over the city; going to the old shabby movie houses of East Liberty; the 21 Negley bus trips; that little candy store in the adjacent blue collar neighborhood of Morningside; and so many evenings with the Buccos game on the radio.

We lived next to the Rothman’s, whose mom, Maxine, gave our mom her family brisket recipe. Mom also got a Flank Steak (Page XX) recipe from her. Sweet honey and soy marinated meat that you char on the grill. Although it’s not strictly a rust belt thing, I include it here because it’s part of our family story...and it’s so damn good. Flank: another tough cut of meat, like brisket and liver, that can be made to be succulent. The last two years on Hampton Street, our parents signed us up for a city-wide voluntary busing program. Busing was a progressive idea of the time, seen as a way to integrate racially segregated neighborhoods by mixing the school kids. This was a controversial thing both city-wide and nationally. Some of the conservative families on the block thought it was a really bad idea...and they were vocal in their opposition. For two years, we rode a city transit bus an hour each way into the projects, to East Hills Elementary School in a low income mostly African American neighborhood. One time when we were racing out to the buses at the end of the day I got jumped by some older kids and hit in the mouth. After the initial shock, it was not really a big deal to me, just the stuff that happens. Mom, however, was traumatized. She had a creeping regret for the busing decision, and so she unfortunately latched on to that incident. Hampton Street was this perfect time of our childhood. Like Jonathan Richman sang, “that summer feeling is going to haunt you one day in your life.” All of that came to an end when my parents split up. We were way too young to understand what was happening, but I do remember a growing sense of disintegration and lots of fighting between them. Eventually one evening, dad hugged us, told he’d always be there for us, and walked down the long front stairs with his last of his things, a bunch of shirts on hangers. After that, we got into a routine where we’d see him every Sunday. And shortly after the divorce we moved off Hampton Street.

In the Croatian Catholic tradition, Easter was a big deal every year. Not only because of its centrality to the Christian faith, but coming out the long east coast winters, I think people were glad for springtime and something to celebrate. After church, there’d be a brunch of ham, boiled potatoes and a tray of root vegetables. You’d pick up the scallion stocks and eat them whole—this always seemed like a real old country thing. In our family the most important thing on the Easter table was Orahnjaca (Page XX), a pastry roll that reveals a spiral pattern when sliced. This delicacy has a sweet flour and egg dough and the darker swirl filling is a walnut, cinnamon and sugar mixture. Each year mom worried that her’s wouldn’t measure up to grandma’s exacting standards. She’d chuckle in later years about how there was always “hand wringing” in the kitchen among the women, both between her and her mom, and also spanning back to her grandma and probably beyond.

Like many Catholics of her era, mom talked about the strictness of the priests and nuns when she was a kid, and about the masses being said in Latin. We sat through a few of those, with the medieval, dead language chants echoing up to the rafters. After her divorce, she attempted to reconnect with the local parish. Because she was a divorced woman, the priest in the neighborhood wanted nothing to do with her or our family. She never really showed it, but I know she was pretty hurt that this institution she had been raised with was not there when she needed it most. Mom started going to the Episcopal church, which she found to be accepting and refreshingly progressive. As a career woman and woman’s rights supporter, she liked that there were women in the clergy. She had us baptized and confirmed at Calvary Episcopal Church in Shadyside, a grand, high steepled church with soaring choral music and ministers who gave philosophical, humanistic homilies—in stark contrast to the more dogmatic Catholic variety. After the divorce, mom moved us to Aspinwall, a small town on the Allegheny River right across from Highland Park. We lived there from the middle of grade school until we went off to college. A-wall is an orderly grid of row houses, with some Victorians and bigger brick houses mixed in. This little working town on the northern side of Pittsburgh could have been the setting for an all-American Frank Capra movie, with a Memorial Day parade through the brick streets, a soda fountain called Fehrmans, and the J&W Variety store on the main street.

This community was more densely crowded and blue collar than highland park, but not quite a full factory worker hood like Lawrenceville, Etna, Rankin or the mill neighborhoods of Homestead and the South Side. Mom moved there so we would eventually feed into Fox Chapel High School, located up the hill in a rustic, old money suburb. In high school, half the kids came from this rich area, the Chaps, and then the other half were us river rats. This economic divide permeated the everything about the school and its social orbits. Everyone knew exactly which group you were in, and cross pollination of the groups was limited. This rich/poor split harkened back to the defining class structure of Pittsburgh’s history: the industrialists vs. the workers. In my research for this book I came across an interesting class pejorative from industrial age Pittsburgh—working folks referred to wealthy people as “cake eaters.” It’s a confectionery class reference, and a bitter echo of Marie Antoinette. Aspinwall was an idyllic neighborhood to grow up in. We played baseball and football down at the field, and street hockey in the winter on playgrounds, tennis courts, streets, or anywhere we could find a patch of asphalt. Every spring, like all kids around the city, we went to Kennywood Park and rode the Thunderbolt roller coaster. When it snowed, we’d be glued to the Jack Bogart morning radio show on KDKA for the school closing list. As he neared the part of the alphabet for our school the anticipation got overwhelming. If school was closed, we’d spend the day playing football in the snow or go out shoveling for money. Whereas I hung with the river rat crowd, roaming aimlessly around town and down along the scrap yards by the river, my brothers were better students and so ended up hanging more with the Fox Chapel kids. They played ultimate frisbee and Dungeons and Dragons. They were tuned in to new wave and progressive music, early punk, and up-and-coming bands like the Police, U2 and the Talking Heads. My friends and I, on the other hand, were all about the rock (now known as “classic rock”) on WDVE, DVE for short. We obsessed over our album collections, and listened to all the head bangers, hair bands and psychedelic troubadours of the late sixties and seventies: Jethro Tull, Floyd, Led Zep, Stones, Allman Brothers, Foghat, Queen, Skynyrd, Doors, Boston, Heart, Bachman Turner Overdrive, ELO, Blue Oyster Cult…. These bands and so many others made up the soundtrack for keg parties, cruising in cars, chasing girls and partying. We moved through a world of jag offs, burnouts, jocks, motorheads, theater freaks—all the usual cliques and high school heroes.

I have to mention my buddies from high school: Rich, Al, Paul, Joe and Doug. Too many crazy stories and memories to include here. Even though we live in different parts of the country and rarely talk anymore, when you grow up with guys and run the gauntlet of adolescence with them, they are your brothers for all time. Eventually, we all got part time jobs. I was a busboy in a fancy mob-run joint by the river in Sharpsburg, where the slick guido waiters made table side Caesar salads with great fanfare. And later I shagged shopping carts at the Thorofare supermarket.

Mom was working a full time corporate job at Gulf Oil, raising three boys, and getting her masters in Toxicology from Duquesne University downtown--all at the same time. Only now with my own kids do I begin to realize how hard that must have been, the strength and focus and crushing exhaustion, all so her three boys could have a better life. Back in the earlier years, mom was an accomplished amateur photographer with her own darkroom. But after the divorce, she didn’t have many interests like that or go out on many dates. Every so often she’d want to just take a drive in her blue Chevy Malibu, with no particular destination. As a side note, I will say this is the same bomber V-8 rig we would cruise around in during high school, occasioned by frequent alcohol-fueled escapades. But mom, under pressures we didn’t begin to grasp, would just want to take a simple drive. This was something people would do before all of the modern entertainment options. It harkened to the days when the automobile was still a novelty. One such time, in a blizzard, we ran out of gas up on the Highland Park loop. She was always running out of gas, or getting lost, or forgetting where she parked her car in the Mall lot. For as book smart as she was, she was absentminded and had a dreamy aspect. These qualities may have been charming to other people, but to us kids they were a little embarrassing.

LaVerne & Ramona LaVerne & Ramona

After college and a stint writing department store advertising in New Jersey, I headed west to California. I had a head full of romantic notions, seeking the Jack Kerouac allure of westward roads. California was exotic for a kid who had never been west of Ohio. I was also seeking better economic prospects than were available in the recession-plagued Rust Belt of the mid-1980s. The heavy industry that built the city had rapidly collapsed under the pressure of foreign steel competition. Overseas competitors had the advantage of cheaper labor and modernized fabrication technology. The once strong labor unions lost power and were blamed for the job losses. From the early 1960s to present, Pittsburgh has lost half of its population due to economic relocation. A side note to this: the diaspora of Pittsburghers accounts for so many Steeler fans attending the team's road games.

With mom moved to Philly and grandma and LaVerne gone, the sense of “home” had fragmented, and there wasn’t a lot keeping me in the Burgh. But I brought a piece of Pittsburgh with me: the recipes. Over the years the foods of my upbringing have become more and more important. And at the same time, I have come to accept that these beloved Rust Belt dishes are totally out of step with contemporary preferences for cooking lighter, healthier and quicker—if anybody cooks from scratch anymore at all. My kids don’t like the old eastern European food, just like my brothers and I didn’t like it when we were growing up. Today, this food remains my touchstone—simple, rich one-pot meals. When we serve stuffed peppers or sadma, it's like my mom is there at the table with us. Near the end of my mom’s life, she had moved out to California to be near grand kids. I told her then that I’d write this story. She would have loved to read it. To be honest, I didn't get along with her a lot of the time. I resented her advise, and she didn't approve of my circuitous life path. And until more recently, I didn’t think much of our family story. Maybe a young man doesn’t know how to appreciate things passed down. But then mortality starts whispering in his ear, and he comes to see his small part in a much longer chain, most of which is obscured and forgotten. And so he tells the story of that little piece of the chain, and he tries to understand his own sense of meaning. I have documented these recipes to honor mom, grandma, and aunt LaVerne, a tribute to how hard they worked to give us a good life. The older I get, the more I treasure the food and memories of growing up in Pittsburgh. It seems like we’re so far from those times now. I am coming to realize all you really own are your stories. Bloodlines and food. Appetite is remembrance. In the end, food may be the best artifact we have for reckoning back into the past. Enjoy these recipes, and love the people around your table! 2017 |

|

© Copyright Confluence Studio. All rights reserved.

|