The Ghost Town has the most beautiful name, drawn from botanical nomenclature, at once Victorian and old western. But I omit it here, based on keeping secret places secret. With a place this unspoiled you have to be careful with the information. The old timer who told Whitey about the town looked long and hard at him before deciding he was worthy to entrust. So we’re carrying that trust forward.

I think that’s why you never got a really clear map to get out there. There was some dead reckoning involved, as if you had to really want to get out there and had the get-up to figure it out. In the age of moment-by-moment self-broadcast and the perfect memory of Google, there are no secrets anymore. I’m a bit concerned about even sharing this account.

Also, full names are not used since people in these stories didn’t likely expect someone to write about all their unguarded moments and put it up on the internet.

I think that’s why you never got a really clear map to get out there. There was some dead reckoning involved, as if you had to really want to get out there and had the get-up to figure it out. In the age of moment-by-moment self-broadcast and the perfect memory of Google, there are no secrets anymore. I’m a bit concerned about even sharing this account.

Also, full names are not used since people in these stories didn’t likely expect someone to write about all their unguarded moments and put it up on the internet.

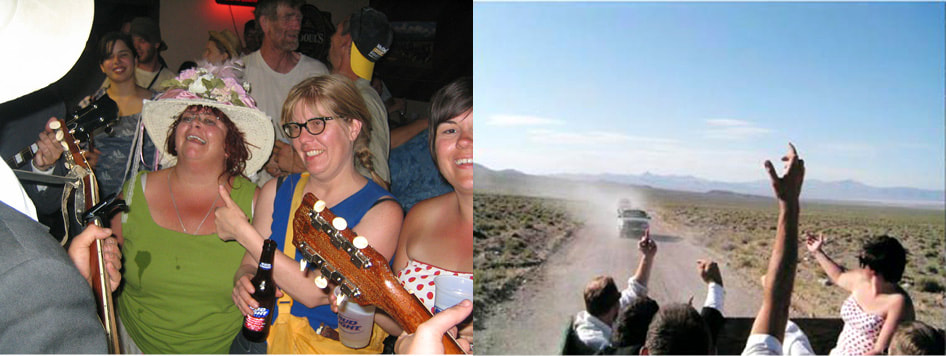

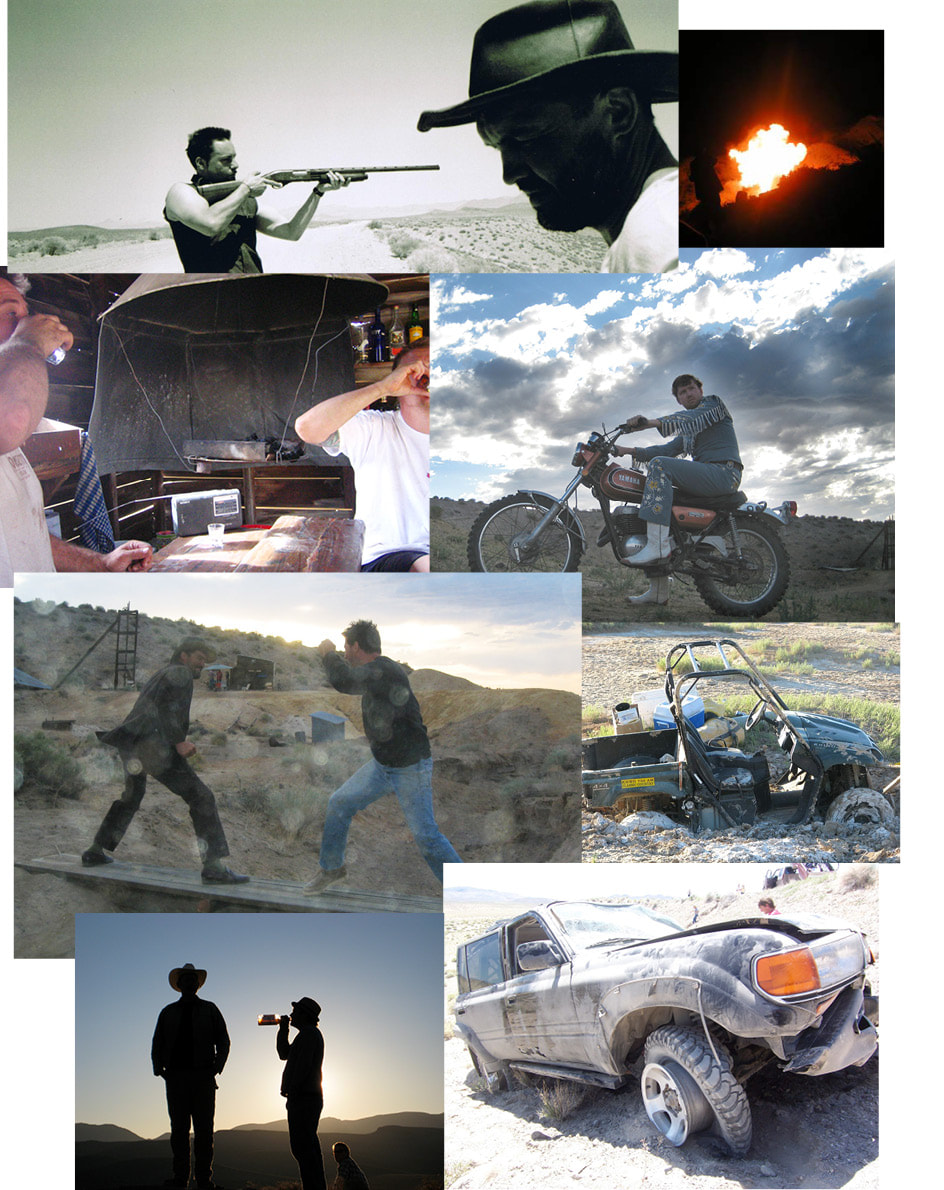

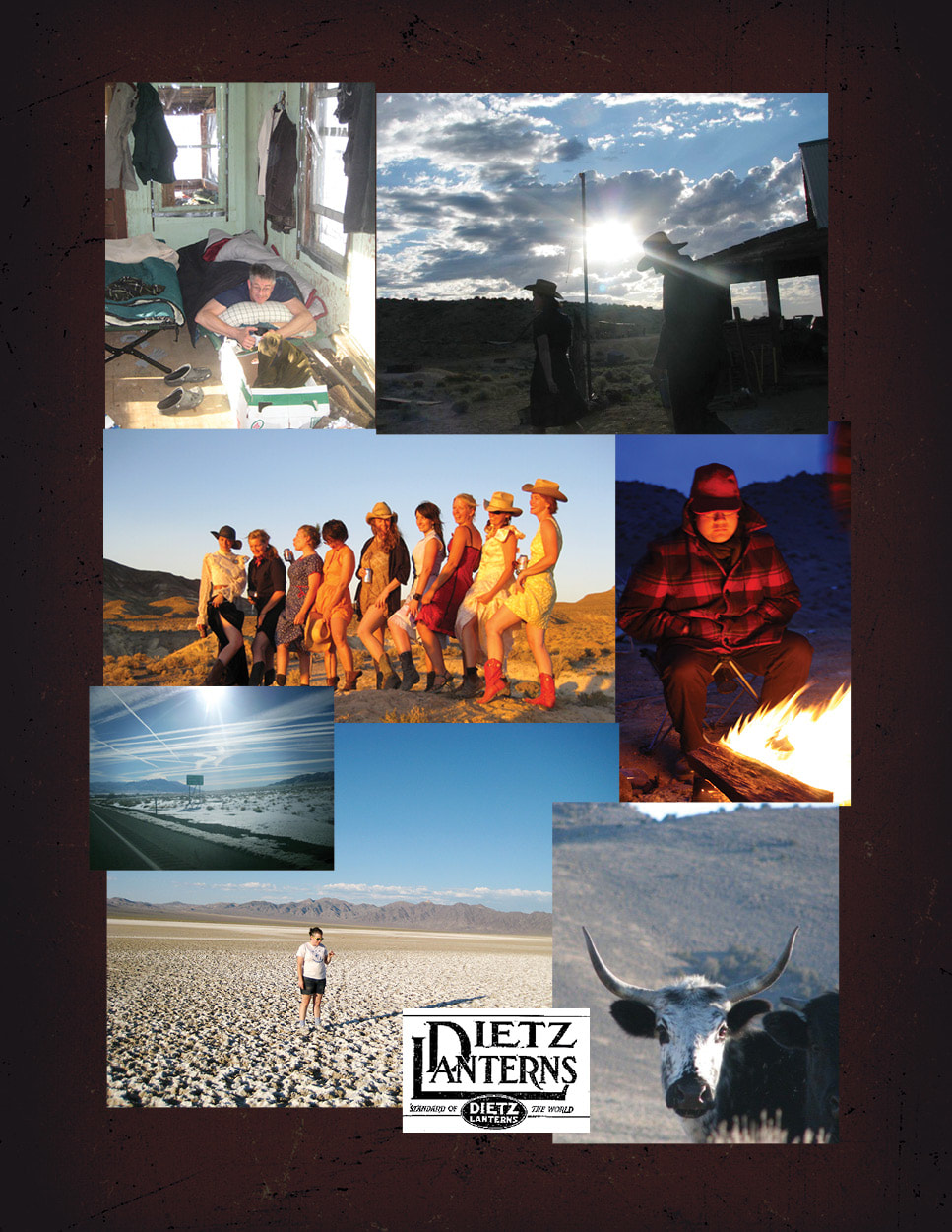

very western story needs certain elements, heroes and rogues, booms and busts, wide open range...and in the middle of it, a lonely little town. And every town needs a mayor and a sheriff. With a wink and nod to old west propriety, Whitey and Jeffy D. were our self proclaimed town officials, on the basis that they found the Ghost Town way up a forgotten road out in the middle of the Nevada desert. Every western story needs calamity--and that is a guy named Preston, a larger-than-life, big-hearted wild man out of Ohio, whose enthusiastic revelry once had to be subdued with a small handful of Tylenol PM crushed up and slipped into his drink. Calamity was served in the Ghost Town by no shortage of antics and characters. There were sages, desert rats and a cat house madam; there were old cowboy songs and honky tonk numbers belted out in a little shack saloon beside an abandoned quicksilver mine. Pastimes among our band of eccentric townies included pyrotechnics, gunplay, heavy drinking, 4 wheeling, drugs, sometimes all in combination--and wrecked cars, as you would expect.

very western story needs certain elements, heroes and rogues, booms and busts, wide open range...and in the middle of it, a lonely little town. And every town needs a mayor and a sheriff. With a wink and nod to old west propriety, Whitey and Jeffy D. were our self proclaimed town officials, on the basis that they found the Ghost Town way up a forgotten road out in the middle of the Nevada desert. Every western story needs calamity--and that is a guy named Preston, a larger-than-life, big-hearted wild man out of Ohio, whose enthusiastic revelry once had to be subdued with a small handful of Tylenol PM crushed up and slipped into his drink. Calamity was served in the Ghost Town by no shortage of antics and characters. There were sages, desert rats and a cat house madam; there were old cowboy songs and honky tonk numbers belted out in a little shack saloon beside an abandoned quicksilver mine. Pastimes among our band of eccentric townies included pyrotechnics, gunplay, heavy drinking, 4 wheeling, drugs, sometimes all in combination--and wrecked cars, as you would expect.

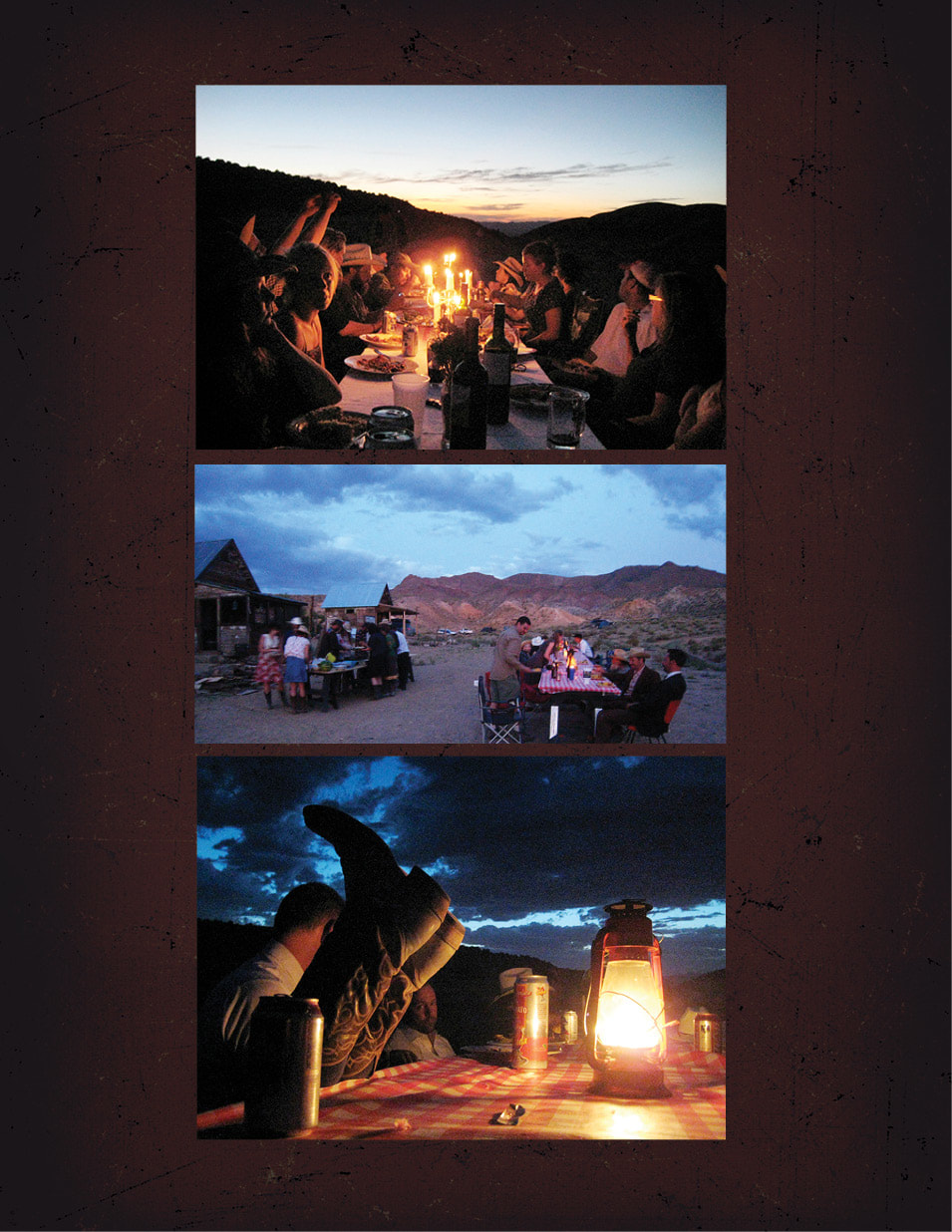

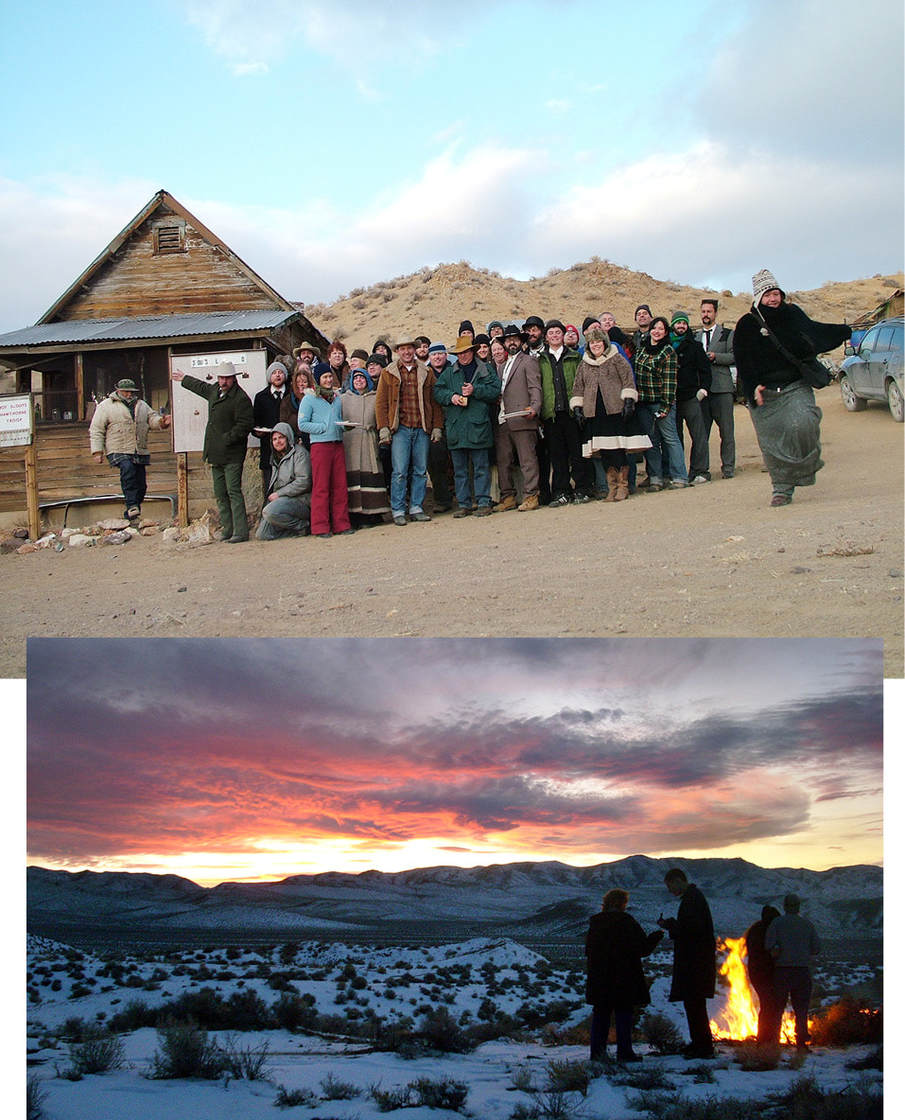

There were calmer pursuits like horseshoes, walks in the sagebrush hills and dutch oven cookery. There were potluck formal dinners in the multicolored dusk, at a long table hammered together out of scrap wood and topped with glowing thrift store candelabras. There were artists, musicians, historians, geographers, and a tall salvage guy whose exact role in life remains hard to describe. There were slackers and teachers and translators and programmers. Above all there was resourcefulness and a DIY ethic--restoration of the old structures, reroofing projects, porch fixing. There was a charming fireman who sang lovely folk ballads and figured prominently in town affairs.

There was a brief span of time, a few years, when we regularly took trips out to the Ghost Town, all of us coming together in this rarefied, otherworldly place. It was more than just weekend camp outs. The place took on a life of its own. Looking back on the experience, the thing I like best is that we made our own world in this godforsaken landscape, a land that the Mayor and his friends found beautiful. I have come to understand this beauty. I have come to share their genuine reverence for western lore. And I can see now how ruins and ‘old shit’ can capture the imagination.

I was first told about the Ghost Town by my friend Señor Bob, a calm, wise understated presence with a subtle but wicked humor. Bob, the consummate tinkerer, builder of geodesic domes, shade rigging, all manner of bicycle improvements. I have known Bob since I moved to Sacramento, 20 years ago. We are both part of a series of midtown Sacramento circles that interconnect, and from which most of the Ghost Town group was drawn. When my three kids were younger I had drifted out of the midtown scene, and had just reconnected with Bob. His descriptions of a bohemian Ghost Town intrigued this family guy who was in some need of adventure.

Bob expertly guided me through preparations for travel way off the grid in a harsh landscape--big military surplus jugs filled with water, fix-a-flat, shade tarps, tools, maps, redundant systems. For some logistical reason he didn’t travel with me. Instead, I found myself driving east on I-80 with three strangers. Another longtime friend, Guphy, had arranged the ride-sharing. She played the role of Ghost Town organizer and cruise director--and I would affectionately add ‘arbiter of all things.’ Originally from Whitefish, Montana, Guphy is a hip Gertrude Stein figure, knowledgeable on books and music, friends with many of the indie and punk bands in Sactown. I worked with her at Tower Books in the early 90s.

Way out east of Reno we filled the gas tank at the last town before turning off the highway onto a small two lane asphalt road. We passed some kind of military bombing range that had carcasses of F-15 fighter planes laid out as targets, and further out until the concrete road came to an end and we were on a dirt road that stretched off into a wide open flat valley. We followed a poorly photocopied topo map with hand scribbled milestones marked to fractions of miles. After a while, we came to a three way intersection of dirt roads out in the middle of this valley. The map seemed unclear and we were confused. One of my passengers was Guphy’s friend Alice. She brought along her English boyfriend, a fussy, bookish guy who seemed put off by the poor quality of the map and the length of the trip.

Everything out here sort of looked the same, and the thought occurred to me of how easily it would be to get turned around and to work yourself into a totally baffled state. We went a few miles up one of the forks and it didn’t seem right so we doubled back to the junction where there now sat an overloaded mid-sixties Volvo sedan, its undercarriage barely clearing the road. Four vaguely hipster-looking passengers were crammed into this rig, ill suited for the rough terrain. We quickly figured out we were all headed to the same place and we were all lost. A few minutes later we saw a dust cloud rapidly approach from the road we had come in on. As it neared, we made it out to be a beat up old Econoline van, the long windowless type that delivery and repair companies use. It skidded to a stop in front of us and the driver’s side window framed a guy with a big black bushy beard and yellow-tinted ski goggles over the rest of his face. He was covered in fine white alkali dust, giving him a ghostly appearance. In this crazy landscape with the beater van and the goggles and the dust he had a menacing Mad Max look about him. He flashed a wide grin and told us to follow him, and that he thought he know the way. Relief, sort of.

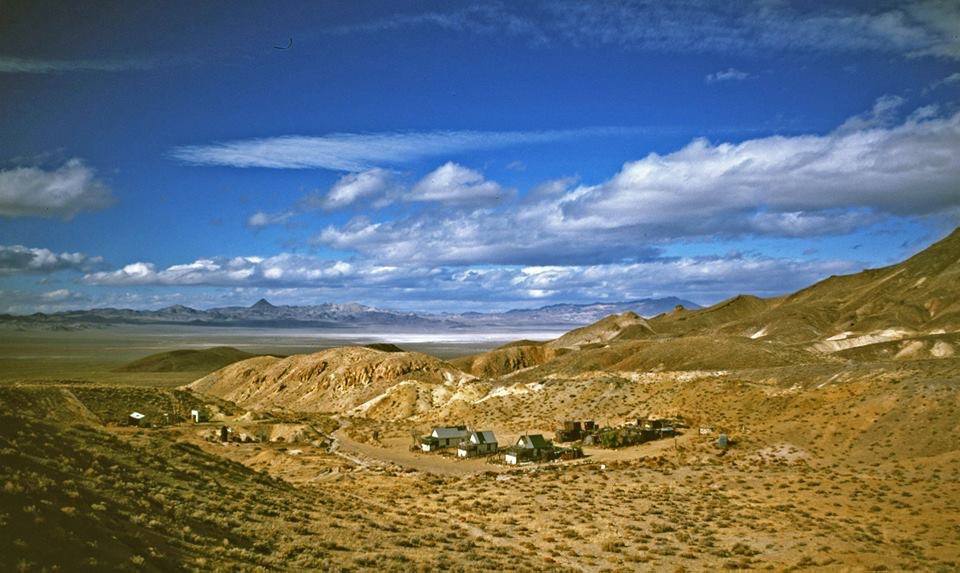

This guy turned out to be Tony, a music producer, sound engineer and drummer. He loved to drive fast and crazy out in the desert. We tried to keep up with him, but couldn’t. I didn’t want to push my old Explorer past 70. Our car full of rookies was perplexed, trying to wrap our heads around why a guy would go that fast, what had possessed him. Alice’s boyfriend had a troubled look on his face at being thrown into this misadventure. Luckily, even though we fell way behind we could follow the big dust cloud Tony left in his wake. We made another turn onto a much smaller, rockier dirt road. Bob had warned me that the sand was soft in places and if I felt the softness to keep the speed up through it and try to steer for firmer ground. He also told me to slow way down at the dried up washes that crossed the road. The bumps were bigger than they looked and they could scrape your oil pan or muffler right off if you hit them too hard. This road got worse and worse as it climbed and wound around some low hills. At times I found I had been gripping the steering wheel really hard without realizing it, consumed with navigating around bigger rocks and trying to apply the right mix of gas and brake. Finally, we crested a ridge and saw down below a little enclave of ruins nestled into this bowl surrounded by low sagebrush hills. There were several simple cabins arrayed amid a ramshackle tangle of falling down wooden structures. Directly beneath us we spotted a small crowd of people beside a shack, drinking cans of beer, hollering and waving up at us.

Bob expertly guided me through preparations for travel way off the grid in a harsh landscape--big military surplus jugs filled with water, fix-a-flat, shade tarps, tools, maps, redundant systems. For some logistical reason he didn’t travel with me. Instead, I found myself driving east on I-80 with three strangers. Another longtime friend, Guphy, had arranged the ride-sharing. She played the role of Ghost Town organizer and cruise director--and I would affectionately add ‘arbiter of all things.’ Originally from Whitefish, Montana, Guphy is a hip Gertrude Stein figure, knowledgeable on books and music, friends with many of the indie and punk bands in Sactown. I worked with her at Tower Books in the early 90s.

Way out east of Reno we filled the gas tank at the last town before turning off the highway onto a small two lane asphalt road. We passed some kind of military bombing range that had carcasses of F-15 fighter planes laid out as targets, and further out until the concrete road came to an end and we were on a dirt road that stretched off into a wide open flat valley. We followed a poorly photocopied topo map with hand scribbled milestones marked to fractions of miles. After a while, we came to a three way intersection of dirt roads out in the middle of this valley. The map seemed unclear and we were confused. One of my passengers was Guphy’s friend Alice. She brought along her English boyfriend, a fussy, bookish guy who seemed put off by the poor quality of the map and the length of the trip.

Everything out here sort of looked the same, and the thought occurred to me of how easily it would be to get turned around and to work yourself into a totally baffled state. We went a few miles up one of the forks and it didn’t seem right so we doubled back to the junction where there now sat an overloaded mid-sixties Volvo sedan, its undercarriage barely clearing the road. Four vaguely hipster-looking passengers were crammed into this rig, ill suited for the rough terrain. We quickly figured out we were all headed to the same place and we were all lost. A few minutes later we saw a dust cloud rapidly approach from the road we had come in on. As it neared, we made it out to be a beat up old Econoline van, the long windowless type that delivery and repair companies use. It skidded to a stop in front of us and the driver’s side window framed a guy with a big black bushy beard and yellow-tinted ski goggles over the rest of his face. He was covered in fine white alkali dust, giving him a ghostly appearance. In this crazy landscape with the beater van and the goggles and the dust he had a menacing Mad Max look about him. He flashed a wide grin and told us to follow him, and that he thought he know the way. Relief, sort of.

This guy turned out to be Tony, a music producer, sound engineer and drummer. He loved to drive fast and crazy out in the desert. We tried to keep up with him, but couldn’t. I didn’t want to push my old Explorer past 70. Our car full of rookies was perplexed, trying to wrap our heads around why a guy would go that fast, what had possessed him. Alice’s boyfriend had a troubled look on his face at being thrown into this misadventure. Luckily, even though we fell way behind we could follow the big dust cloud Tony left in his wake. We made another turn onto a much smaller, rockier dirt road. Bob had warned me that the sand was soft in places and if I felt the softness to keep the speed up through it and try to steer for firmer ground. He also told me to slow way down at the dried up washes that crossed the road. The bumps were bigger than they looked and they could scrape your oil pan or muffler right off if you hit them too hard. This road got worse and worse as it climbed and wound around some low hills. At times I found I had been gripping the steering wheel really hard without realizing it, consumed with navigating around bigger rocks and trying to apply the right mix of gas and brake. Finally, we crested a ridge and saw down below a little enclave of ruins nestled into this bowl surrounded by low sagebrush hills. There were several simple cabins arrayed amid a ramshackle tangle of falling down wooden structures. Directly beneath us we spotted a small crowd of people beside a shack, drinking cans of beer, hollering and waving up at us.

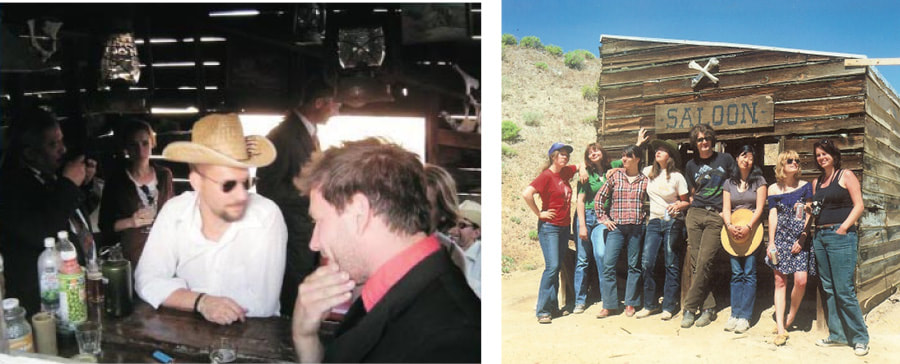

We were greeted by maybe twenty people, friends and other folks I didn’t know, and we commenced our initiation into one of the mainstays of town life, daydrinking and holding forth around the ‘Saloon,’ a 10x15 foot tin roofed shack that had once been a blacksmith shed. Cattle bones nailed in an X above the door provided a rustic decoration. Right away I was struck by the spirit of this party, people coming and going, bursts of laughter, smoking cigarettes, sipping red beer, playing cards, knocking back shots of cheap whiskey, all the sunglasses and straw cowboy hats. And I got a strong initial sense of the magic of the place, the impossibly blue sky, the heat, the occasional breeze off the valley, this rambling haphazard rowdy social gathering, all merging together in a comfortable vibe. We walked into the Saloon to find the Mayor, otherwise known as Whitey, behind the bar. It was a nautical themed carved wood affair, the glossy lacquer worse for wear, and fronted by buoys and fishnet. They had rescued this bar from someone’s garage and trucked it in from Humboldt. The irony of nautical kitsch in the Great Basin was not lost on me—part of a whole random, mismatched ethic, the older and more weathered the patina, the better. Whitey greeted us. He had bright blue eyes and boyish good looks. He was quick to pour us beers, grabbing glass mugs from an odd assortment of vessels stored in bins that had once housed metalworking stuff.

As the afternoon wore on, others took turns behind the bar, whoever happened to be standing there. Nothing was organized but somehow it all worked. The walls were full of knick knacks: rodent skulls, artwork, found objects. It wasn’t much of a structure. The wood was so weathered you could see sunlight between boards. There was a little transistor radio playing old country music through a steady buzz of static. This station broadcast from a small town out on the main highway, and was something of a town ritual: three parts good old tyme country--Hank Williams, Lefty Frizzell, Doc Watson type stuff. And one part was a schmaltzy 70’s era brand of country music. So everyone vaguely followed along, playing a sort of radio Russian roulette, appreciating the obscure treasures, and groaning at the duds. The broadcast featured local public service announcements, hokey ads, and the national anthem played everyday at high noon.

As the afternoon wore on, others took turns behind the bar, whoever happened to be standing there. Nothing was organized but somehow it all worked. The walls were full of knick knacks: rodent skulls, artwork, found objects. It wasn’t much of a structure. The wood was so weathered you could see sunlight between boards. There was a little transistor radio playing old country music through a steady buzz of static. This station broadcast from a small town out on the main highway, and was something of a town ritual: three parts good old tyme country--Hank Williams, Lefty Frizzell, Doc Watson type stuff. And one part was a schmaltzy 70’s era brand of country music. So everyone vaguely followed along, playing a sort of radio Russian roulette, appreciating the obscure treasures, and groaning at the duds. The broadcast featured local public service announcements, hokey ads, and the national anthem played everyday at high noon.

In the shade of the Saloon I took in all this activity. Through the open window frames I could see other people further out, and beyond, maybe 100 yards away down a slight grade were the cabins, three in a row, in what was referred to as ‘town,’ as in town proper. A few paces away from the Saloon stood a 20 foot tall wooden hoisting derrick and beneath it, the mine itself, a square timber framed opening that descended into the earth several hundred feet. Through the window I noticed a woman in the intermediate distance tearing it up on a 90cc dirt bike, repeatedly skidding out and going full throttle up a steep bank as far as she could go. Her efforts and the high pitched whine of the 2-stroke engine were just one of many intersecting and overlapping movable parts of this afternoon menagerie. After a while, the dirt bike girl walked into the saloon, mildly annoyed and talking about how she fucked up her leg. This was Ella, who carried herself with an elegance and refinement that was a non-sequitur in that moment. She sidled up to the bar, proceeded to knock back two shots of whiskey in quick succession and then headed back out to take another go at the dirt bike. At that moment I had one of those ‘you’re not in Kansas anymore’ realizations.

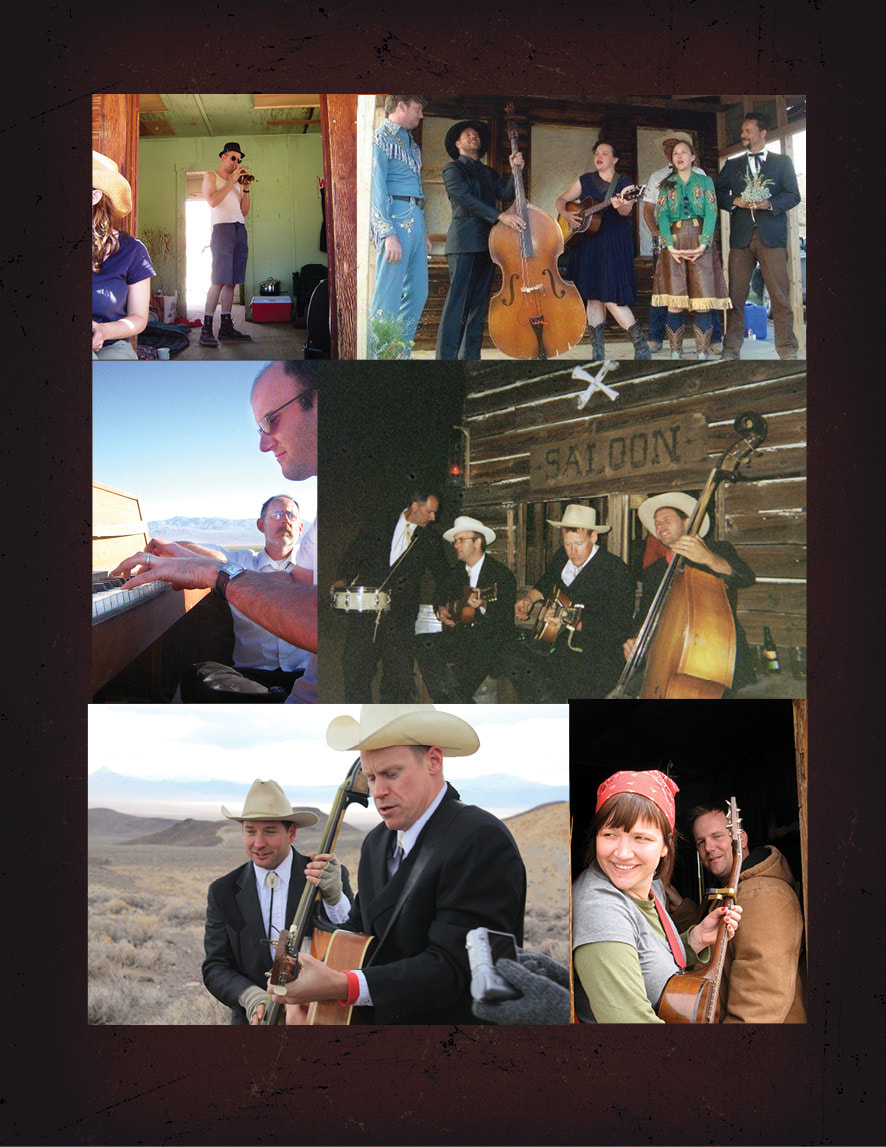

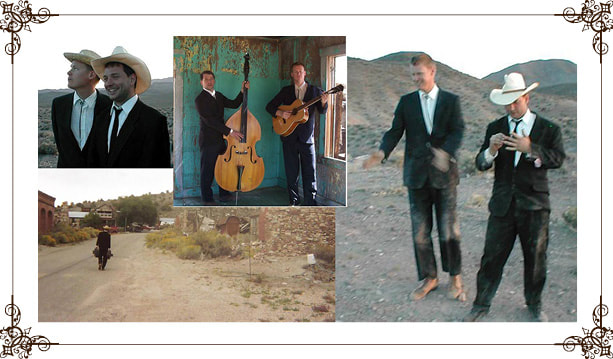

Over the course of the next several years I visited the Ghost Town many times, and through those experiences became friends with a wide circle of people. It would be easy to dismiss our little group as city folk playing dress up out in the hinterlands. A quick look at stripmall America reveals no shortage of drugstore cowboys in heroic, rough hewn gear. But our Ghost Town group were not posers. The core part of the group made friends with people in many of the little hardscrabble towns that dotted the desert. The old miners, ranchers and desperadoes who lived out there saw Whitey’s love of the Nevada country. And many of the locals were just plain charmed by the band that was at the center of our group, called the Alkali Flats. I’ve watched it happen over and over again--the Flats’ talent, enthusiasm, self deprecating modesty, and their deep knowledge of traditional country music won people over everywhere they went. It was cool to see the older folks respond. For a lot of them, this was the long forgotten music of their upbringing. They’d get up and two-step right there beside us younger city folks, all of us drinking and whooping it up in some little tinderbox dive bar.

The band's origin consisted of Whitey and Chris dressing up in old suits and with their guitars walking into a low down barroom in Belmont. There were a handful of salty miners hunched over the bar. These these guys just stared at the strangers and there was a moment where the musicians didn't know what to say. So Whitey blurted out, "The band is here!" Once the barkeep realized it wasn't a scheme to get money, they were allowed to play. As they played, the bartender started phoning townspeople to come down and hear this legit old country band. They packed the place and played until the wee hours...and were given accommodations in an old stone cabin nearby.

One of the great things about the Flats is that they weren’t angling to be some kind of big, self-important sensation. That purity of motivation translated to a really genuine sound that ran the gamut from spare, lonely murder ballads to barroom sing a longs. Their first album, called Killing Time, was a crude recording made in the Saloon. It was recorded with what the liner notes called a ‘crap-ass microphone’ purchased at a Nevada pawn shop. You hear people cheering and singing along in the background. In the early days, the sound was unamplified, a simple combination of guitar and stand up bass. The band has changed over the years, but Whitey, Chris and Miller, the original three members, remain at its core.

Miller, the drummer, is a lanky bespectacled fellow with a bird-like, somber disposition. He has been a fixture on the Midtown Sacramento scene for years. Miller and Señor Bob grew up together in the suburbs of Sactown. It’s hard to put your finger on what it is about Miller. He has a bemused curiosity after niches and quirky things, an esoteric knowledge, and a wide, diverse circle of friends. His gift is that he is receptive to what life offers, and he takes people for who they are. He just sort of finds his way to the good things in life...and often this means the overlooked things and the free things--night canoe trips, campfires, any number of random and obscure destinations. The one that comes to mind is an annual gathering of delta farmers known as the ‘Liver Feed.’ He has no regular job--rather a combination of things, including architectural salvage, double-hung window restoration and dealing antiques on Craigslist and eBay. His parents owned a strip club in Sacramento in the 1960s. With the money they left him, he bought a burned out 1860s era house in midtown. For the past ten years he’s been slowly and lovingly restoring the place with period materials. His drum kit consists of a single snare drum that he plays standing up. Minimal is Miller’s style. Depending on the situation, he’ll beat on just about anything--milk jug, beer can, tin bucket. One of the Flats albums lists him in the credits as playing the cardboard box. He’s the steady presence in the band, standing in the background, laying down a solid beat.

The driving force of the band, at least vocally, is Chris, the fireman. He’s a trim, handsome guy with close cropped blond hair and tattoos covering his upper arms and torso. He was a bike messenger in San Francisco, a bike mechanic and came up in the punk scene. Like Whitey, he’s the kind of guy who is good at a lot of things: carpentry, screen printing, repair of all kinds. Chris loved to get a little loose out in the desert as much as the next guy, but he was also one of the most responsible guys out there. On more than one occasion his paramedic training saved the day. He’s the guy who sort of makes the band come alive. With just the simple combination of strumming and vocals he has the power to captivate. Among many, many great songs, there are two ballads that he covers that are signatures for me: Darcy Farrow, a forlorn murder ballad, and one called Saint of San Joaquin.

Whitey, the ceremonial mayor, came out west from Ohio in the late 80s. He and a few pals took an epic road trip in a beater Cadillac convertible, and ended up in Sacramento. That was back when California college tuition was still a real bargain. He went to school and bounced around the midtown scene, playing in various bands including a surf punk group called the Tiki Men. At some point, he became fascinated with ghost towns. He tells of how he got more and more immersed in western history and got on a quest to visit ever more remote and interesting places in Nevada. He, Jeffy and small groups of their friends had been going out to the Ghost Town for ten years before the bigger trips began. In the 90s, he wrote and produced a cut-and-paste zine called Western Lore. When you meet Whitey, you immediately get a sense of his midwestern background, the worn work boots, his no-nonsense, salt-of-the-earth vibe--he’s a decent, genuine guy with a comfortable manner and a big heart. He studied art and writing in school and now works as an independent builder and finish carpenter. He’s always saying what an average musician he is, but as far as I can tell, he’s a pretty damn good guitar player and singer. Whitey conjured this whole Ghost Town thing and he is the heart and soul of it.

Over the years there have been an assorted cast of characters in the band, fiddlers, horn and piano players, various guitarists. One of the most purely talented of them was Keith. He’s a bit older than the rest of the group and is pretty well known in Northern California traditional music circles. He plays damn near every instrument, and plays really well. He’s especially good with the intricate finger picking of the mandolin. Keith often wears dark glasses, and when he hunches over the lap steel he looks like some kind of savant channeling the old tyme musical legends. His life is all about music. He gives lessons, plays in several bands, and the guy makes his own instruments. These things don’t look ‘homemade.’ When he finishes a guitar, it’s a high sheen instrument, probably more finely crafted than most. Because the Flats play in what are sometimes ‘full contact’ situations, Keith has been called upon several times to repair instruments that have been damaged in the fray.

The Flats would play anywhere--around a campfire, on a porch, busking on the sidewalk. They would trade instruments between songs. At one point they screwed a bottle opener onto the back of the stand up bass. The act of opening a beer on the bass always offered an amusing interlude. They were best in these informal venues surrounded by friends and ricocheting banter. This type of loose music circle has a warm human dimension compared with modern electronic music listened to in the lonely bubble of headphones. One of the more odd places the band played was on the back of a flatbed truck. The catalyst for this adventure was a guy named Anton, who worked some kind of indeterminate salvage operation out in the little farm town of Winters, CA. He had a flair for elaborate Burning Man-style engineering projects, and seemed to know a whole network of junkyard tinkerers. Anton came across this junker upright piano and arrived out at the Ghost Town with it strapped to an industrial flatbed truck. The next afternoon, the Flats got up on that truck and headed for a little desert town called Mina, trailed by several cars. As our janky parade rolled down the main street, the band was going for broke. We were met by a crazy drunk guy named Dale, who was a big fan of the Flats. He got up on the truck and danced a goofy little jig and then lead our group into one of the nearby watering holes. We partied there all night with a pretty rough crew of locals, including a big gal named Queenie. She was vivacious and loud, wearing a feather boa and a big church hat. It turned out Queenie was the madam of a real live cathouse down the road, although no one personally verified that story. That piano ended up in cabin Number 2, where it remains to this day (cabin nomenclature is pretty straightforward).

The band has made several cross-Nevada trips, playing in military towns where barroom fights sometimes broke out. I heard one story where they played right through a melee, edging out of the line of swinging fists and chairs, hoping their equipment wouldn’t get damaged. As good as they were in a party scenario, some of the best music came around campfires and in calmer settings. I remember trying to take a nap in the back of my truck one afternoon and hearing the sweetest impromptu music drifting across town. It was some guys from the Mad Cow String Band out of Davis, CA, some of the Flats and maybe Richie, a well known accordion player and good friend of the group. They were noodling around in Number 2. I wanted to get up and go over there, but I couldn’t get up...the plaintive sounds of the fiddle and banjo reached me as I drifted in and out of sleep in the heat. An accomplished musician named Olsen would play trumpet some mornings, the poignant, solitary sound echoing through a quiet, hung over town. Olsen seemed to play everything: trumpet, tuba, piano, banjo and several types of mini horn.

The band has made several cross-Nevada trips, playing in military towns where barroom fights sometimes broke out. I heard one story where they played right through a melee, edging out of the line of swinging fists and chairs, hoping their equipment wouldn’t get damaged. As good as they were in a party scenario, some of the best music came around campfires and in calmer settings. I remember trying to take a nap in the back of my truck one afternoon and hearing the sweetest impromptu music drifting across town. It was some guys from the Mad Cow String Band out of Davis, CA, some of the Flats and maybe Richie, a well known accordion player and good friend of the group. They were noodling around in Number 2. I wanted to get up and go over there, but I couldn’t get up...the plaintive sounds of the fiddle and banjo reached me as I drifted in and out of sleep in the heat. An accomplished musician named Olsen would play trumpet some mornings, the poignant, solitary sound echoing through a quiet, hung over town. Olsen seemed to play everything: trumpet, tuba, piano, banjo and several types of mini horn.

A few years ago Scotty & Sasha joined the Flats. This husband and wife duo had a band called The Poplollys that played sweet lullabies and vintage pop tunes. When they hooked up with the Flats there was an instant chemistry. The two bands started intermixing at various gigs. Eventually they joined the Flats and moved from the hills of Auburn down to Sacramento. With Scotty & Sasha in the band, the sound became more full and has moved a little in the direction of honky tonk and the Maddox Brothers & Rose. Scotty sings, plays guitar, lap steel and stand up bass. He’s got a great deadpan sense of humor. He quips with Chris between songs and engages in cute banter with his wife. Sasha’s rich, soulful voice reaches to a sublime place, and her calm, always-smiling female energy is a nice counterpoint to the rest of the boys.

For a guy who grew up listening to 80s arena rock and pop radio, the Flats introduced me to whole different worlds of music.

As we went out there more frequently, people developed a sense of propriety toward the town. It was unspoken but understood that the Ghost Town was beautiful partly because it wasn’t really owned by anyone. So this wasn’t ownership, more like stewardship. People started to repair little things, tacking up screen on the windows, fixing hinges. And then the projects got bigger, aimed at keeping the structures from reaching the point of irreversible decay.

Big work parties were organized, with whole trucks of equipment mobilized: generators, ladders, all manner of cordless tools. The crazy quilts of tarpaper on the cabin roofs were replaced with salvaged but weather-tight corrugated aluminum. A wooden floor was installed over the saloon’s dirt floor--old boards were used so that it looked like it had been there forever. Cabin number 4, previously a crooked heap, was reconstructed and made safe to occupy. The town ‘Public Works Department’ was lucky enough to have a few carpenters and builders, so there was a high level of craftsmanship on these projects, and a fidelity to original design. This crew lived in the do-it-yourself mode. Homemade and self-made was better than store bought. This value extended beyond restoration and carpentry to include cooking, silkscreen printing, design of all kinds and music making.

Relocating and improving the fabled Honey Hut was a memorable work project. The Honey Hut was the town’s outhouse that stood partway up one of the berms. This project was notable not only because it involved the mission critical aspect of bodily function, but because it was an imperative set down by the ladies in the group who were highly displeased with the state of the hut. Although I wasn’t on that trip, I heard tales of the superhuman exploits of a one-man wrecking crew known as Preston. Preston embraced the Ghost Town experience like no one else, and became one of the central characters of the group, owing to his big spirit, his extreme exploits and his imposing stature. In the story of the Honey Hut, this man-beast apparently devoured a breakfast of a dozen eggs and a pack of bacon, then put on long johns, coveralls, boots and a plantation hat, and went out into 100 degree weather and spent 8 hours at brute manual labor--clearing debris, swinging a pickaxe like a madman, and then leading an effort to manually move the structure and re-anchor it over the new latrine hole. The new Honey Hut was a big improvement. It featured side-by-side toilet seats and offered a beautiful vista out onto the wild landscape. This double configuration pushed the boundaries of bathroom taboo. I was never bold or freaky enough to go tandem style, although I’m sure some people did. If you wanted a more minimal experience, there was always Whitey’s chair. This was an old Victorian antique style chair into which he had cut a hole in the middle of the seat. There was a bar affixed to it that held a roll of ‘shit tickets.’ You’d grab the chair and some reading material and off you’d go over the hill, to commune with nature in style.

Big work parties were organized, with whole trucks of equipment mobilized: generators, ladders, all manner of cordless tools. The crazy quilts of tarpaper on the cabin roofs were replaced with salvaged but weather-tight corrugated aluminum. A wooden floor was installed over the saloon’s dirt floor--old boards were used so that it looked like it had been there forever. Cabin number 4, previously a crooked heap, was reconstructed and made safe to occupy. The town ‘Public Works Department’ was lucky enough to have a few carpenters and builders, so there was a high level of craftsmanship on these projects, and a fidelity to original design. This crew lived in the do-it-yourself mode. Homemade and self-made was better than store bought. This value extended beyond restoration and carpentry to include cooking, silkscreen printing, design of all kinds and music making.

Relocating and improving the fabled Honey Hut was a memorable work project. The Honey Hut was the town’s outhouse that stood partway up one of the berms. This project was notable not only because it involved the mission critical aspect of bodily function, but because it was an imperative set down by the ladies in the group who were highly displeased with the state of the hut. Although I wasn’t on that trip, I heard tales of the superhuman exploits of a one-man wrecking crew known as Preston. Preston embraced the Ghost Town experience like no one else, and became one of the central characters of the group, owing to his big spirit, his extreme exploits and his imposing stature. In the story of the Honey Hut, this man-beast apparently devoured a breakfast of a dozen eggs and a pack of bacon, then put on long johns, coveralls, boots and a plantation hat, and went out into 100 degree weather and spent 8 hours at brute manual labor--clearing debris, swinging a pickaxe like a madman, and then leading an effort to manually move the structure and re-anchor it over the new latrine hole. The new Honey Hut was a big improvement. It featured side-by-side toilet seats and offered a beautiful vista out onto the wild landscape. This double configuration pushed the boundaries of bathroom taboo. I was never bold or freaky enough to go tandem style, although I’m sure some people did. If you wanted a more minimal experience, there was always Whitey’s chair. This was an old Victorian antique style chair into which he had cut a hole in the middle of the seat. There was a bar affixed to it that held a roll of ‘shit tickets.’ You’d grab the chair and some reading material and off you’d go over the hill, to commune with nature in style.

Work projects raised a dilemma related to preservation: not wanting to impose modernity onto the town ruins--wanting to let time take its natural course--but also not wanting the town to completely crumble down. Everyone struggled with this. We were all caught up in the romanticism of looking backward. What does it mean to like old things, to be wrapped up in the lore and forgotten stuff of the past? Being in town, you could feel the ghosts, and you wondered about the souls who lived and toiled there, what life must have been like. I am visited sometimes by the fleeting notion that our attraction to the aesthetic of ruins and decay is some kind of secret rumination over our own inevitable ruin.

The writer Somerset Maugham had this well known quote about wild and depraved life on the French Riviera. But if he had ever made it out to Nevada, he’d of ended up with the same conclusion, it’s a “A sunny place for shady people.” That line made it into one of the Flats’ songs, and it sums up the renegade, lawless spirit of the Silver State, the hard living and constant chase after luck. From the days of the Comstock Lode and into the era of mobsters and casinos, Nevada held the fleeting promise of striking it rich. On top of that, there’s the oddball history of atom bomb testing and the alleged UFO landings. It’s where people come for hurry-up marriages and divorces, to hide out, and to drift around. And it’s where people come to get lucky in another sense—prostitution has been legal in parts of Nevada for decades. The most infamous of the brothels, the Mustang Ranch, was run by a flashy honcho named Joe Conforte, who tangled with the law and the mob, and ended up fleeing to South America to avoid fraud indictments. On the way to the Ghost Town there was a roadside whore house that was a landmark in the area for decades. As you passed by, you’d see a compound of trailers and double-wides surrounding a main structure. The fluorescent box sign by the road featured three sexy, high-booted woman in various dance poses. The place burned down a few years back, and the charred remains are a spooky waypost on the trip.

For our group of city folk, the renegade spirit of Nevady was part of the attraction. Being out there seemed to make everybody more loose and wild. There was this little 15-foot high bump of a hill in town that came to be known as Dumb Mountain. It symbolized Drunk City Man’s ambition to conquer the natural world in enumerable foolish and dangerous ways--involving dirt bikes, ATV’s and other manner of combustion-propelled vehicles. In the general category of ‘stupid but possibly inspired’ there were mostly jackass stunts and mishaps involving guns and rigs. There was Willie and Ella in the family station wagon going up a very steep talus hill over and over again, almost making it to the top each time. A bunch of us sat transfixed, unable to intervene, astounded by the balls of what they were doing. At one point someone turned the wheel wrong and the car went perpendicular to the fall line and almost rolled. And Tony, who guided us into town on the first trip, would get air off hillsides in the Econoline. A Hispanic guy named Berto, old friends with Señor Bob, would 4-wheel out to remote mines, many of which were tucked way up mountain sides on very poor roads. He had an old jacked-up Land Cruiser that he drove with a high degree of skill and authority. But I remember gripping hard at points, thinking about how Berto had likely smoked the peace pipe all day.

For our group of city folk, the renegade spirit of Nevady was part of the attraction. Being out there seemed to make everybody more loose and wild. There was this little 15-foot high bump of a hill in town that came to be known as Dumb Mountain. It symbolized Drunk City Man’s ambition to conquer the natural world in enumerable foolish and dangerous ways--involving dirt bikes, ATV’s and other manner of combustion-propelled vehicles. In the general category of ‘stupid but possibly inspired’ there were mostly jackass stunts and mishaps involving guns and rigs. There was Willie and Ella in the family station wagon going up a very steep talus hill over and over again, almost making it to the top each time. A bunch of us sat transfixed, unable to intervene, astounded by the balls of what they were doing. At one point someone turned the wheel wrong and the car went perpendicular to the fall line and almost rolled. And Tony, who guided us into town on the first trip, would get air off hillsides in the Econoline. A Hispanic guy named Berto, old friends with Señor Bob, would 4-wheel out to remote mines, many of which were tucked way up mountain sides on very poor roads. He had an old jacked-up Land Cruiser that he drove with a high degree of skill and authority. But I remember gripping hard at points, thinking about how Berto had likely smoked the peace pipe all day.

An old friend of mine by the name of Mahoney came out on a trip and got caught up in one of the more savage incidents. He’s a high school English teacher and a former newspaper editor. The Nevada desert experience was quite a bit outside his more tame orbit. When he arrived, we joked about this, and posed him with a bottle of Tequila and a shotgun...a souvenir photo for his wife. The next morning when I joined the gathering of coffee drinkers, things seemed especially subdued. Then I noticed Mahoney’s face was all scraped up. The night before, the whole group had driven out to a town about 45 minutes away where the Flats were playing at a favorite bar. On the way home, Mahoney and his other friend in the group, JR., had been in a wicked accident. After breakfast several carloads of us drove out to visit the accident site and collect what belongings remained in the vehicle. The outing felt like some kind of a morbid field trip--people grabbed cameras and beers for the road. When we got to the spot, we walked back along the skid marks and realized how badly J.R. had missed a turn in the dirt road. He was a mountain biker, an adrenaline junkie, and he was likely well into the drinks. We measured where the tire tracks ended--25 yards airborne and then another 25 rolling and bouncing. The rig was totaled. The airbags had saved their lives. All of us were snapping pics, drinking beer and smoking cigarettes. We posed Mahoney and J.R. beside the shattered and dented up SUV. The survivors were dourly heroic with cut up faces and a stunned sort of disposition. They had faced down death, and everybody wanted a piece of it.

Although our crowd was mostly artsy lefties, a good number of people defied the stereotype and enjoyed shooting guns. In the town’s heyday, people walked around strapped with holsters and loaded pistols. On my first trip out, I observed this series of encounters involving KP, an old friend of my sister-in-law’s. She’s this feisty, smart, redheaded woman wearing a holster and side arm over her floral print prairie dress. She was going around drawing on people. ‘KP, Is that a real gun?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Is it loaded?’

‘Let’s just find out, fuckhead.’

‘KP, put the gun down, goddammit!’ Her standoffish act conjured a nice sense of menace mixed with absurdity.

On the far side of the Saloon there was an improvised shooting range. You’d shoot down into a big field filled with junk left from the mining years. You can’t beat the thrill of firing a .357 Magnum and picking off rusted remains of water boilers, coffee cans, car engines, fenders, beer bottles. On several occasions, after dark, Chris would heard the whole group down in the cover of a ditch as a precaution, and then he’d shoot a 30/30 into a cluster of propane tanks and gas cans that had been hiked up to the next ridge--the primal joy of a 40-foot tall fireball mushrooming off the desert sand! It’s not uncommon for guys in the firefighting line of work to have a fascination with, and perhaps unnatural attraction to, things pyrotechnic. But Chris, as I mentioned, was one of the most responsible guys out there. In taking about guns, I have to mention Señor Bob’s Okie cousins who would come out to Nevada on their own trips. Bob has shown me photos of them with their array of automatic weapons and explosives, the volume and caliber of which was befitting a separatist militia.

So many jackass moments...a bottle rocket fight at point blank range, instigated by someone throwing someone else’s hat in the fire. Anton in his powder blue leisure suit hoisting a 4-foot long ABS pipe potato gun and launching spuds a hundred yards out into the sky blue. Drunk sled riding down a steep snowy hill on a scrap sheet of aluminum. And there was the time Chris had to actually physically disarm someone who got too drunk playing cards in Number 2 and got all pissy, waving a pistol around. And another time someone’s wasted friend climbed several hundred feet down the mine and passed out in the garbage heap at the bottom. Some brave soul went down there to carry him out. These incidents scared people.

At the center of the calamity and dangerous living you could usually find Preston. With his beat up, brown three-piece corduroy suit and leather cowboy hat, he moved about the scenes of the Ghost Town as if he were the second coming of Emperor Norton, magnanimously reviewing the troops and checking on his far flung kingdom. While I recount some of Preston’s over-the-top antics, what should not be lost is that the man has an over arching sense of gratitude. His ability to express his love for life in an unembarrassed way is his defining gift. I happened to be along for one of Preston’s infamous misadventures.

The story of the ‘Ring Toss’ ends in the Ghost Town, but it begins up on Mount Shasta, the iconic 14,000 foot glacial peak that towers over the Northern California landscape near Redding. Preston and his younger half-brother Tommy, affectionately known as Lamb Bottom, had gotten interested in snow hiking and climbing peaks. They had notions of climbing Mt. McKinley. I had been up Shasta a few times and had snow climbed many of the peaks in the Desolation Wilderness, so they turned to me for guidance. I agreed to lead them up on a weekend in June. It turned out to be the same weekend of a big Ghost Town trip. So we decided to head out there after the climb. We got to Shasta City, rented the two of them crampons and ice axes and got to the trailhead that night. We pulled bags out and slept in the dirt for a few hours, setting an alarm for 3 a.m.

We were only about a quarter mile up the pitch black trail when Preston just spilled his guts about how his 17-year marriage was falling apart. Tommy and I were mostly silent during this anguished, rambling confessional. For all the wild things this guy had done, there was a conventional side: he had been an engineer in the Navy. They had kids and a house. He had been a Boy Scout Troop leader, done all the parent things. And now he seemed to be diverging from his wife’s more conventional world. We slogged for 8 hours up steep faces of snow, and made it to the summit around noon. In the thin air he smoked a cigar and went around high fiving people. The handful of REI-clad athletic climbers at the top didn’t know what to make of this guy. As we descended and neared what would be a total of 14 hours on the mountain, Preston seemed to get stronger and stronger. Tommy and I were fading and he was enthusiastically greeting hikers who were on their way up, sharing bits of information with them about terrain and conditions. On the bottom part of the descent, we got to a resting point at the top of a steep bowl. That’s where he got cell phone reception and called his wife to proudly share the news of our triumph. Tommy and I lay there watching him, barely able to move from exhaustion. The conversation didn’t go well. Apparently she was completely dismissive of the summit accomplishment. Preston hung up abruptly, then we watched him pull his wedding ring off and huck it way down into the bowl. He unleashed a torrent of expletives and we were looking at each other, stunned by this development, wondering whether we had really just witnessed that.

We got back to the cars, drank a few beers, returned the rented gear, and immediately set out on the five hour drive to a town in the middle of Nevada, where the Flats were playing that night. We had to keep switching drivers to avoid falling asleep at the wheel. We got there at nearly 11 that night. The band was done and heading back to the Ghost Town. Tommy and I laid up in a cheap motel room, unable to continue. Preston joined the rest of the group and ended up partying all night. Tommy and I make it out to the Ghost Town late the next morning. Preston was still going strong, in some kind of delirious state, drinking more beer and shots.

Someone needed cigarettes and it was decided we would drive out to get some in a little town 45 minutes away. Preston got behind the wheel of his pickup and Tommy, a guy named Zack and I got in the cargo bed. Along the way, the three of us in the back started playing this game that became known as Hillbilly Skeet. We took turns with the Remington over-under, shooting empty beer bottles out of the sky going 60 mph down a dirt road. We were shooting them as fast as we could drink them. It was all fine until Preston decided to show off and tilt up the truck bed with his newly installed hydraulic dumper. We gripped where we could and begged him to stop, hoping he wasn’t completely out of his mind from the accumulation of partying all night, the weed, the breakup of his marriage, and the many morning drinks he had consumed. It was one of those ‘I don’t give a fuck’ moments where you know what you’re doing is not advised, but you do it anyway. Somehow, no one got hurt.

Later that afternoon Preston was sloppy, wrestling in the dirt with all comers, aggressively hugging people, slobbering and bleeding on them. Several people got together and sneaked Tylenol PM into his beer. That did the trick. The big man was out for a much needed rest. When he woke up several hours later, he was sheepish and apologized to everyone.

As a footnote to this story, Preston ended up marrying a woman named Liz, a environmental scientist who works in the nuclear industry. They had a big, heartfelt wedding out in the Ghost Town on a bitter cold Thanksgiving weekend. Since then, he has settled down a good bit and they have been inseparable. In my mind, Liz has earned the formidable distinction of being the woman who tamed the mighty Preston!

On the other side of the spectrum from daredevil antics and debauchery there was a sincere appreciation of the place--the remoteness, stillness and quiet, the sense of emptiness, the natural beauty. The desert has a sweep and grandeur unmatched by any postcard of an ocean or a snowy mountain. It’s what compelled guys like Maynard Dixon to paint bold, color-saturated western landscapes. I asked Whitey once ‘what was it about the desert?’ ‘The blue of the sky’ he said. It sounds overly simple, but there’s something about the unreal iridescence of the blue and the flatness of the land. Distance and the quality of the light tend to force the world into a reductive set of lines and color blocks. And Whitey knows something about color—among all of his other talents, he is an accomplished landscape painter whose work is sold in galleries. For those of us who toil in cubicles and mundane interiors, being out in the desert always felt like good fortune. The concerns of city life seemed to dissolve away into the bigness of the land.

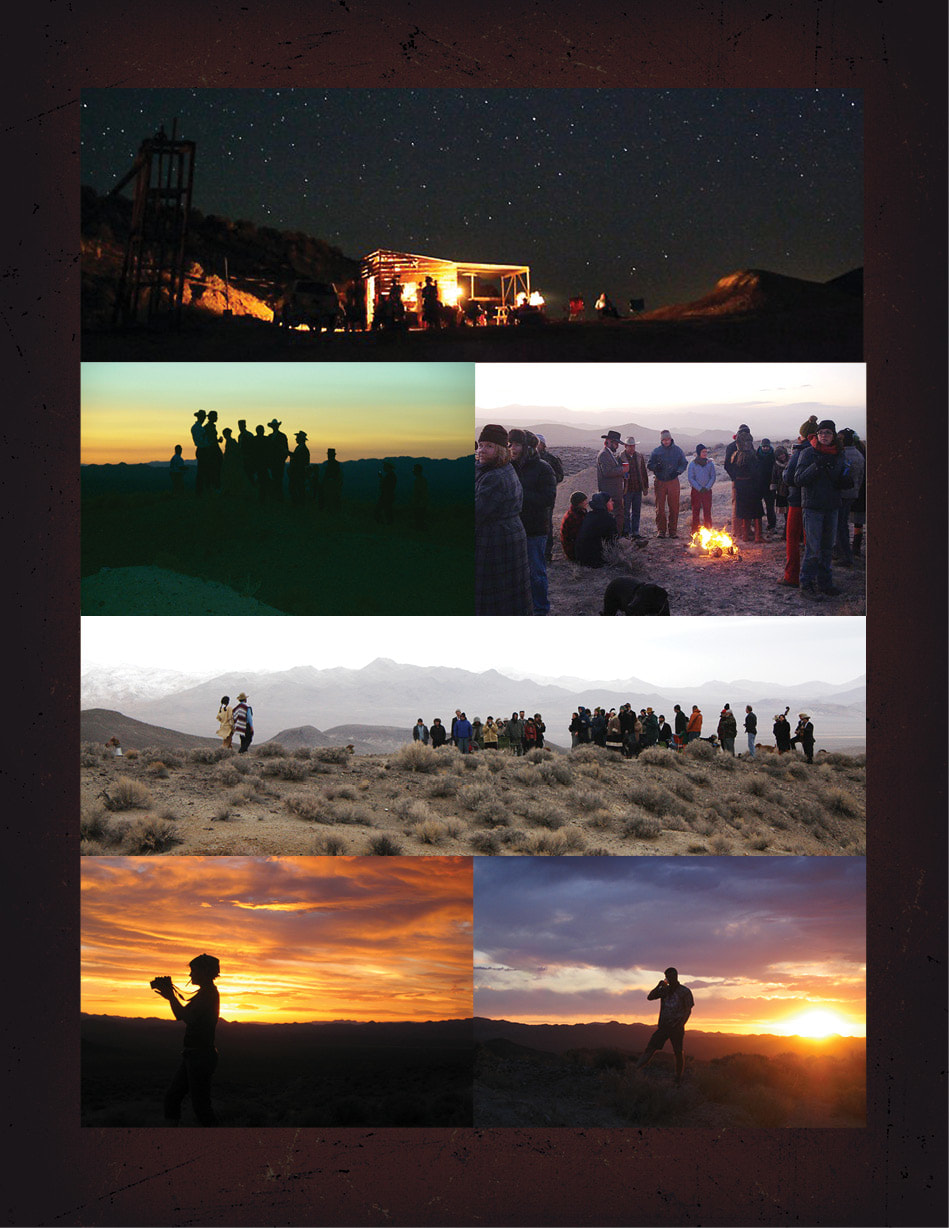

When you find yourself walking in the Elysian Fields, of course you do the tourist thing and pull out your camera. Most of us were powerless to resist the allure of photography, even though playing the intrepid photog was sort of a well worn role. Our device-centric age has trained us to reflexively reach for digital capture as a shorthand expression of more profound things. As a result, there were these absurd scenes where everyone was shooting the same picture. But I think the self conscious act of taking snapshots was a fair tradeoff for the record of what seems like a lost time. Among so many, there are a few I keep coming back to: a long exposure photo of the Saloon and mine derrick silhouetted against an evening sky. The gradation from light to deep blue is pinpointed with millions of stars, and the Saloon windows are glowing with lantern light and just the suggestion of activity inside. Another indelible series of images is from what became known as Sunset Point. Around dusk people would walk up onto the ridge above town. It overlooked the broad sweep of the valley below. There were these amazing photos of groups of us standing under the dramatic gathering dusk, the sky and distant peaks washed in incomprehensible shades of purple, orange and deep yellow.

When you find yourself walking in the Elysian Fields, of course you do the tourist thing and pull out your camera. Most of us were powerless to resist the allure of photography, even though playing the intrepid photog was sort of a well worn role. Our device-centric age has trained us to reflexively reach for digital capture as a shorthand expression of more profound things. As a result, there were these absurd scenes where everyone was shooting the same picture. But I think the self conscious act of taking snapshots was a fair tradeoff for the record of what seems like a lost time. Among so many, there are a few I keep coming back to: a long exposure photo of the Saloon and mine derrick silhouetted against an evening sky. The gradation from light to deep blue is pinpointed with millions of stars, and the Saloon windows are glowing with lantern light and just the suggestion of activity inside. Another indelible series of images is from what became known as Sunset Point. Around dusk people would walk up onto the ridge above town. It overlooked the broad sweep of the valley below. There were these amazing photos of groups of us standing under the dramatic gathering dusk, the sky and distant peaks washed in incomprehensible shades of purple, orange and deep yellow.

The Ghost Town offered a forum for all manner of interesting and seat-of-the-pants culinary pursuits. The one that immediately comes to mind involves Der Skipper, a stout guy with a sort of European intellectual eccentricity about him, and a flair for retro fashion. Skip works as a German language translator and blogs about his culinary adventures--fermenting of pickles and kraut, corning beef, curing bacon--all kinds of exotic and oddball recipes--the weirder the better. As we townies awoke one morning and stumbled out to meet the day, we were transfixed by the vision of Skipper decked out in formal whites and wearing an Imperial pith helmet. He was completely self-possessed, methodically and silently digging a hole in the hard ground. Totally random. As we settled in around Number 2 with cups of coffee, he went right about his work. Once the hole was dug he started a fire in it, and then produced a whole suckling pig. By now, seeing that he had quite an audience, Skipper executed some unspeakable sexual pantomimes with the pig, to our great amusement. Then he wrapped it in foil and wet banana leaves, prepped the bed of coals, dropped the swine in, and covered the whole thing with scraps of aluminum. An all-day pit roast.

Whitey and Jeffy D roasted turkeys in this same way. For Preston’s wedding, my brother and I roasted a pig in a metal box at the request of the betrothed couple. We picked up this freshly slaughtered pig that was hanging on a hook in a back road Nevada butcher shop, and rolled into town with the beast strapped to the roof. But those were the exceptions. Most often we cooked with cast iron, especially the dutch oven, either dropped right into the fire, or with carefully counted charcoal briquettes on top and bottom. People made all sorts of things in them. Miller attained a degree of proficiency making a much loved cornbread. He’d serve you up a piece and then top it with little pour of Rebel Yell bourbon. The high art of dutch oven cookery was to stack ‘em two or three high...a whole meal that utilized the efficiency of sharing heat between pots. That was a fine sight.

Willie was another guy who embraced camp cooking. I’ve got this fragmentary memory of encountering him one morning cooking a skillet of bacon on the campfire. He’s got a mess of tangled red hair and he’s in this light blue, elaborately embroidered Nudie Suit that makes him look like a cross between a 1960s country singer and an ironic, flamboyant Kentucky Colonel. He’s squinting into the climbing sun and says in an affected drawl, ‘I’m gonna cook bacon aaaaallllll day long.’ And he was, in fact, partial to long haul cooking. He and Ella would bring out an old tyme set of fire irons. He’d spend whole afternoons getting good and liquored, hand cranking a rotisserie bar full of foul. Then there’s the image of Preston at breakfast—stirring potatoes with a stick, frenetically carrying on three conversations at the same time while finishing cans of beer that had been abandoned the night before. ‘Beach Beer’ is the term he used to describe this disturbing practice.

Whitey and Jeffy D roasted turkeys in this same way. For Preston’s wedding, my brother and I roasted a pig in a metal box at the request of the betrothed couple. We picked up this freshly slaughtered pig that was hanging on a hook in a back road Nevada butcher shop, and rolled into town with the beast strapped to the roof. But those were the exceptions. Most often we cooked with cast iron, especially the dutch oven, either dropped right into the fire, or with carefully counted charcoal briquettes on top and bottom. People made all sorts of things in them. Miller attained a degree of proficiency making a much loved cornbread. He’d serve you up a piece and then top it with little pour of Rebel Yell bourbon. The high art of dutch oven cookery was to stack ‘em two or three high...a whole meal that utilized the efficiency of sharing heat between pots. That was a fine sight.

Willie was another guy who embraced camp cooking. I’ve got this fragmentary memory of encountering him one morning cooking a skillet of bacon on the campfire. He’s got a mess of tangled red hair and he’s in this light blue, elaborately embroidered Nudie Suit that makes him look like a cross between a 1960s country singer and an ironic, flamboyant Kentucky Colonel. He’s squinting into the climbing sun and says in an affected drawl, ‘I’m gonna cook bacon aaaaallllll day long.’ And he was, in fact, partial to long haul cooking. He and Ella would bring out an old tyme set of fire irons. He’d spend whole afternoons getting good and liquored, hand cranking a rotisserie bar full of foul. Then there’s the image of Preston at breakfast—stirring potatoes with a stick, frenetically carrying on three conversations at the same time while finishing cans of beer that had been abandoned the night before. ‘Beach Beer’ is the term he used to describe this disturbing practice.

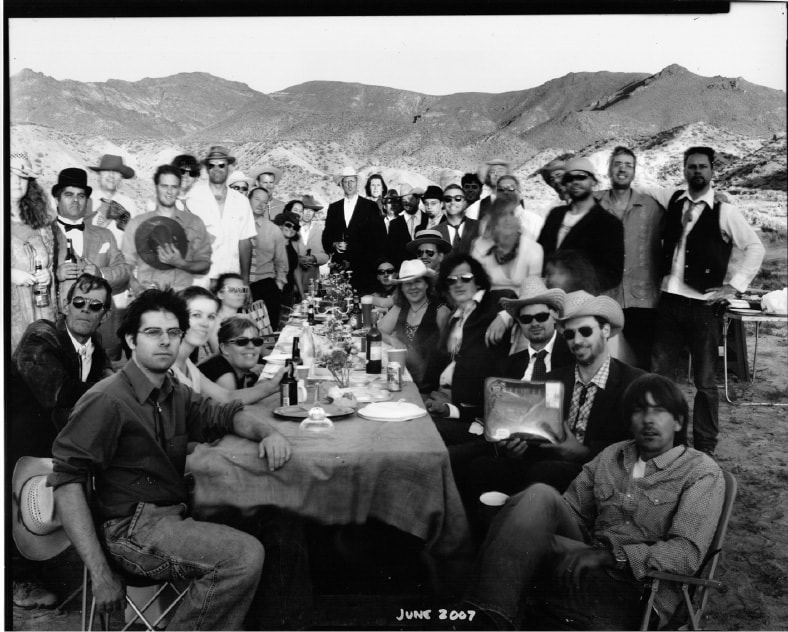

On a more pleasant note, the topic of camp eats would not be complete without mentioning the banquet dinners we had on some of the bigger trips. No matter how dusty, sweaty and beer soaked you got during the day, come late afternoon, you got cleaned up and dressed up fancy. And everyone gathered around a 40-foot long table that Whitey and Miller had constructed out of old doors and wood they scavenged from the ruins. They built it so it could be disassembled into sections and stowed under one of the porches. This was quite a civilized scene, right there in the middle of that rough country. Picture a long table in the gloaming, lit by Dietz railroad lanterns, laden with a bountiful feast: pots and skillets and trays and candelabras, wine bottles, an assortment of gaudy stem ware, cans of cheap beer. And you gazed down the table and saw hombres in bolo ties, ladies in hats & gowns, shabby bon vivants, swells and dandies adorned with a whole mish-mash of western and Victorian fineries. There was Suero in his dignified top hat, and over there, Mister Olsen, the tuba player, in boater and bow tie, the picture of second hand panache. If there ever was a time in this whole experience when I may have allowed myself the fanciful notion that the Ghost Town was real and we were back in the old west, it was during these dinners. One time, a guy named Adam took a silver gelatin group portrait. Like Mathew Brady, he hunched under the black cloth of an ancient large format camera set on a rickety wooden tripod. We had to hold still for the long exposure. In the quadratone print, you see all of us frozen in the sort of formal bearing common to historical photography.

In attempting to tell the story of the Ghost Town, the pageant of incidents and characters seems to swirl in and out of focus. There’s no way to place them in any sort of linear narrative. The experience itself wasn’t linear, especially given my probable lack of sobriety during many of these times. So these accounts are an haphazard recollection pulled from the reaches of surreal, alcoholic memory.

Zack was a notable character, a Midtown Sacramento guy who had moved up to Portland some years back. He was pretty involved in the motorcycle scene, and affected a menacing biker punk look, complete with studded leather jacket, spiked wristbands, Fu Manchu goatee, and piercing eyes. He had a jackrabbit wit and a quick mind that was addled by it’s own quickness. There was a bit of cognitive dissonance with him, in that he actively sought the outsider role, but then ended up complaining about being the outsider. He would jokingly challenge Whitey’s fictitious role as mayor, threatening to mount some kind of insurgent campaign to unseat the mayor. If you’d bring up the fact of his constant orneriness, he’d reply, ‘My hate keeps me warm at night.’ But deep down, he was softer and more good hearted than the ‘bad man’ image he cultivated. He was always tossing off twisted and clever bon mots. He coined Dumb Mountain, and his dense, freewheeling rants on the Yahoo message board were entertaining, or perplexing.

When Preston and Zack were together they taunted each other and fed off the playful animosity. They looked like two roughnecks out of a Sergio Leone movie, unshaven and worn. One time they were goofing around and it turned into a full on fight. They ended up rolling around in the dust, and someone had to step in and break it up.

Most of Zack’s act was a sort of finely honed put-on, but there was one time I did see him pretty rattled. I had walked up to the Saloon the morning after a long night, and there he was, sitting by himself in the bright morning light in the wreckage of the party aftermath. He was chain smoking and had a look on his face like he’d seen a ghost. The night before he had eaten several of Preston’s very potent Humboldt brownies, one of which was probably way too much. In his stupefied state, he had climbed up to the top of the ridge and curled up in a fetal position in the sagebrush. He stayed up there all night without a blanket, trying to ride out the overdose. It wasn’t long before people were kidding him that he’d gone up to the mountaintop and seen God.

Dave Smith is another townie of note, an interesting guy who played in punk bands in Sacramento in the late 80s and 90s. He has nearly completed the goal of riding his vintage Ducati all the way around the world, and seemed to be constantly hopping to the next overseas teaching gig--most recently Korea and Saudi Arabia. There was the memorable sight of him, this unshaven hairy guy who looked a little like John Belushi, staggering around town in a sexy little cocktail dress and hoisting a large mug of beer to any and all passers by.

There was a beautiful laziness about passing time in the Ghost Town—afternoons playing horseshoes and cards, or walking up to a little trickle of a spring higher up in the hills. And there were many mornings spent chasing the shadow of Number 2. In the summer, you’d start to feel the heat by 9 or 10. Everyone would be sitting in the shadow of cabin Number 2 drinking coffee, stoking the fire, eating whatever breakfast might be passed around. As the sun rose and the morning wore on, that shadow got smaller and smaller, creeping ever closer to the wall of the cabin. And everybody just kept moving their chairs, to stay in the shadow until there was only a foot or two left...and the disappearance of the shadow signaled the end of the morning. In this life of full calendars and to-do lists, it’s a rare luxury to have nothing to do but chase a shadow.

Señor Bob seemed to be always busying himself with some sort of project or another. He was known to wander off to the edge of town midway through a night’s festivities and release what he called UFOs. Although these floating lanterns are now commercially available, he made them out of plastic bags suspended by coat hanger frames over a tin foil pan of burning oil. The things would sail off glowing into the night. When a UFO was sighted from across town at the Saloon, a big cheer would go up. Dumb Mountain was a fine launching spot for mortar fireworks purchased at the nearby Indian reservation. Many a night the sky was filled with these spectacular pyrotechnic blooms as big as what an official municipality might shoot off.

We all spent many good times around the campfire in the Ghost Town with the various antics going on all around in a seemingly haphazard way, always surrounded by these amazing people. Guphy, looking at the proceedings with raised eyebrow and a little smirk, her keen sense of the realities and rules of engagement, her wry commentary. Guphy was pretty close with a gal named Marletta. There is a sweetness about Marletta. She always had a big hug and a smile for you. Like me, she wasn’t usually in the middle of the action—more content to watch the goings-on and get in a good one liner here and there. And Jeffy D, the Sheriff. He’d say his piece--he’d say it intently and emphatically. There’d always be hearty laughter mixed in there. Jeffy is just a lovable guy. He’d go like crazy and then be in bed by 9 o’clock. That was one of his trademarks. Honestly, I could go on and on, but my words and generalized descriptions seem to fall short of adequately conjuring these amazing people and the strong sense of camaraderie.

Señor Bob seemed to be always busying himself with some sort of project or another. He was known to wander off to the edge of town midway through a night’s festivities and release what he called UFOs. Although these floating lanterns are now commercially available, he made them out of plastic bags suspended by coat hanger frames over a tin foil pan of burning oil. The things would sail off glowing into the night. When a UFO was sighted from across town at the Saloon, a big cheer would go up. Dumb Mountain was a fine launching spot for mortar fireworks purchased at the nearby Indian reservation. Many a night the sky was filled with these spectacular pyrotechnic blooms as big as what an official municipality might shoot off.

We all spent many good times around the campfire in the Ghost Town with the various antics going on all around in a seemingly haphazard way, always surrounded by these amazing people. Guphy, looking at the proceedings with raised eyebrow and a little smirk, her keen sense of the realities and rules of engagement, her wry commentary. Guphy was pretty close with a gal named Marletta. There is a sweetness about Marletta. She always had a big hug and a smile for you. Like me, she wasn’t usually in the middle of the action—more content to watch the goings-on and get in a good one liner here and there. And Jeffy D, the Sheriff. He’d say his piece--he’d say it intently and emphatically. There’d always be hearty laughter mixed in there. Jeffy is just a lovable guy. He’d go like crazy and then be in bed by 9 o’clock. That was one of his trademarks. Honestly, I could go on and on, but my words and generalized descriptions seem to fall short of adequately conjuring these amazing people and the strong sense of camaraderie.

For the first many years, the Ghost Town trips were just a handful of people, a very different experience than the bigger trips. As these wild parties and big trips continued, a tension crept up within the group. The car wrecks, accidents and generally unsafe behavior became a big issue for Whitey. The Ghost Town offered a rare bit of unlimited freedom—a playground with no rules, no clocks or responsibilities. But it turns out the people most attracted by total freedom are typically those least able to handle total freedom. The Mayor felt a strong sense of responsibility for the town and he became increasingly concerned by the freewheeling, wild part of the experience. There was a basic midwestern decency hardwired in Whitey. On one of the trips, an ATV rolled and a guy broke his arm. Everyone in town had been drinking all day. Whitey volunteered to drunk drive him 50 miles over rough road to the nearest ER. Having to show up at the hospital like that seemed to rattle him. In addition to his concern for people, I think he loved the place so much he didn’t want it to be poisoned by some sort of tragedy, someone getting killed or paralysed. It’s a thing where enthusiasm and personal magnetism often got the better of good judgement. So at some point, the big trips just stopped happening. The Yahoo message board went quiet. People continued to go out there in smaller groups. This low key, less rowdy approach was more in keeping with Whitey’s reverence for the desert. For me, there was a built-in conflict regarding the dangerous part of the experience. The shooting, wildness and daredevil stuff is part of the fabric of it, part of what made it interesting...but ultimately that was the undoing of the Ghost Town.

When Whitey was out there a few years ago, a BLM ranger drove into town and questioned him closely about who had put all of the stuff in the Saloon and in the other structures. He convinced the Land Management guy that he didn’t know anything about it. The Ranger remained pretty suspicious. He ripped all of the stuff out of the Saloon and left Whitey with a stern warning. It seemed like the long tentacles of civilization were closing in our little desert paradise.

When Whitey was out there a few years ago, a BLM ranger drove into town and questioned him closely about who had put all of the stuff in the Saloon and in the other structures. He convinced the Land Management guy that he didn’t know anything about it. The Ranger remained pretty suspicious. He ripped all of the stuff out of the Saloon and left Whitey with a stern warning. It seemed like the long tentacles of civilization were closing in our little desert paradise.

Then the unthinkable happened. On one of Whitey’s small trips about a year ago, he approached over that final ridge and looked down on the town to see a devastating sight--the Saloon had burned completely to the ground. I can’t imagine his heartbreak at that moment, the shrine at the center of this whole cherished experience, just gone, a tangle of charred smoldering beams. Word quickly spread among our group. The speculation ran a few different ways. The worst scenario was that the overzealous BLM guy had torched it himself—some kind of renegade high desert justice. A more likely scenario was that some other group had a fire in the little Saloon stove and that started the blaze. Other people did occasionally find their way to the town and camp out there. And it would have been easy, especially in heavy wind, for the stove to get out of control. The night before Preston’s wedding there were only a handful of us still up very late at the bar, and the wood stove actually caught fire to a corner of the structure. Someone noticed and we managed to douse it just in time—but another 30 seconds and there would have been big, unstoppable flames. This incident marked an end of sorts. If every western story follows some kind of mythic arc--from discovery to boom and then to bust—then we had arrived at the bust.

This past October I went out there for the first time in a long time. There were six of us, including Whitey, Sasha, Señor Bob, Miller, Suero and Jeffy D. It was great to feel the desert air again, the sense of wide open space. It felt like we were hiding out from media and machines and city life. Whitey and I spent the better part of an afternoon sitting on the porch of Number 3, drinking red beer and whiskey, watching the day burn down. On Saturday morning, Jeffy set up his green Coleman stove on the porch and cooked up sausage and eggs for everyone, the stub of a cigarette hanging out of his mouth as he worked the skillet. Near the end of the weekend I carefully suggested to Whitey that maybe we should have a drink up at the Saloon for old time’s sake. I was surprised when he agreed to this. In the late afternoon we walked up there on that little hill with a bottle of Makers and some chairs. We dragged the remains of charred beams away and cleared the area with the sides of our boots. Then Whitey and the five of us sat there in the dusk on that scorched earth and had a toast and talked vaguely about whether or not it would be a good idea to rebuild it. I’m glad we did that.

You could look at the Ghost Town and conclude it was merely a bunch of slackers, bohemians, drunks and nostalgics partying in the desert. But that’s not really accurate. Jeffy D. put it this way: all the things people are always looking so hard to find are right there in that town. The thing that I liked best is that we made our own place out of an abandoned piece of wasteland, and saw the beauty in things others had discarded. There was a sincere attachment to this stark little enclave of ruins and to the lore of bygone times. It had to be this way. Our friends didn’t go in for all the latest prepackaged recreation. Part of the story was about freedom and independence. What could be more American than that? So our janky band of sentimental fools might have been real Americans after all. It makes a strange sort of sense. Even now, I hear Preston’s booming battle cry punctuating the desert afternoons: ‘I love freedom!’ We were a town of misfits, in the best possible sense, clever, funny, original people, unapologetically eccentric people. My little story may be about the love of Nevada and western lore, but it’s as much a love letter to these friends I have made. The Ghost Town is a gift that these guys gave to me.

You could look at the Ghost Town and conclude it was merely a bunch of slackers, bohemians, drunks and nostalgics partying in the desert. But that’s not really accurate. Jeffy D. put it this way: all the things people are always looking so hard to find are right there in that town. The thing that I liked best is that we made our own place out of an abandoned piece of wasteland, and saw the beauty in things others had discarded. There was a sincere attachment to this stark little enclave of ruins and to the lore of bygone times. It had to be this way. Our friends didn’t go in for all the latest prepackaged recreation. Part of the story was about freedom and independence. What could be more American than that? So our janky band of sentimental fools might have been real Americans after all. It makes a strange sort of sense. Even now, I hear Preston’s booming battle cry punctuating the desert afternoons: ‘I love freedom!’ We were a town of misfits, in the best possible sense, clever, funny, original people, unapologetically eccentric people. My little story may be about the love of Nevada and western lore, but it’s as much a love letter to these friends I have made. The Ghost Town is a gift that these guys gave to me.

Along the trail you’ll find me lopin’

Where the spaces are wide open,

In the land of the old A.E.C.

Where the scenery’s attractive,

And the air is radioactive,

Oh, the wild west is where I wanna be.

Mid the sagebrush and the cactus,

I’ll watch the fellas practice

Droppin’ bombs through the clean desert breeze.

I’ll have on my sombrero,

And of course I’ll wear a pair o’

Levis over my lead B.V.D.’s.

Ah will leave the city’s rush,

Leave the fancy and the plush,

Leave the snow and leave the slush

And the crowds.

Ah will seek the desert’s hush,

Where the scenery is lush,

How I long to see the mushroom clouds.

‘Mid the yuccas and the thistles

I’ll watch the guided missiles,

While the old F.B.I. watches me.

Yes, I’ll soon make my appearance

(Soon as I can get my clearance),

‘Cause the wild west is where I wanna be.

— Tom Lehrer, covered by the Alkali Flats

Where the spaces are wide open,

In the land of the old A.E.C.

Where the scenery’s attractive,

And the air is radioactive,

Oh, the wild west is where I wanna be.

Mid the sagebrush and the cactus,

I’ll watch the fellas practice

Droppin’ bombs through the clean desert breeze.

I’ll have on my sombrero,

And of course I’ll wear a pair o’

Levis over my lead B.V.D.’s.

Ah will leave the city’s rush,

Leave the fancy and the plush,

Leave the snow and leave the slush

And the crowds.

Ah will seek the desert’s hush,

Where the scenery is lush,

How I long to see the mushroom clouds.

‘Mid the yuccas and the thistles

I’ll watch the guided missiles,

While the old F.B.I. watches me.

Yes, I’ll soon make my appearance

(Soon as I can get my clearance),

‘Cause the wild west is where I wanna be.

— Tom Lehrer, covered by the Alkali Flats

|

© Copyright Confluence Studio. All rights reserved.

|