|

Pittsburgh Sports Memories

The memories of a sports crazed kid who grew up in Pittsburgh in the 1970s. These two sections are part of a larger Pittsburgh memoir called Rust Belt Kitchen.

Pittsburgh is the quintessential working class town, imbued with a strong sense of blue collar pride that you readily notice of when you are there. It’s hard to pinpoint, but there’s an unvarnished quality to the people, most apparent in the accent, that distinctive raw, nasal raspy sound. Nothing shows off the accent better than the pejorative “jag off”, especially dropping it paired with an F-bomb: “Hey you fuckin’ jag off, that’s my sister.” The other trademark colloquialism spoken with the same rasp is “yinz,” meaning “you all,” as in “What time yinz goin’ dawn-tawn for the game?”

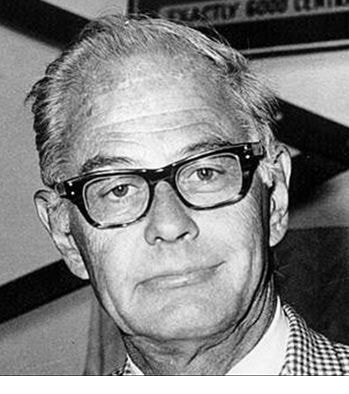

Art Rooney, "The Chief." Art Rooney, "The Chief."

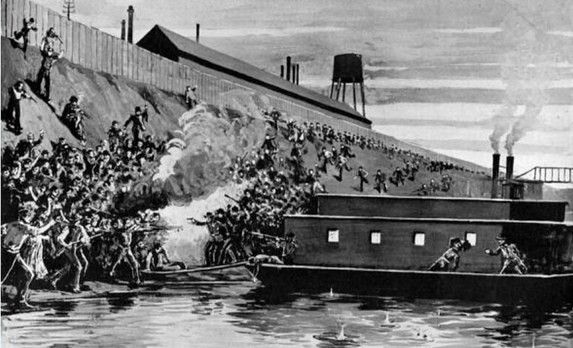

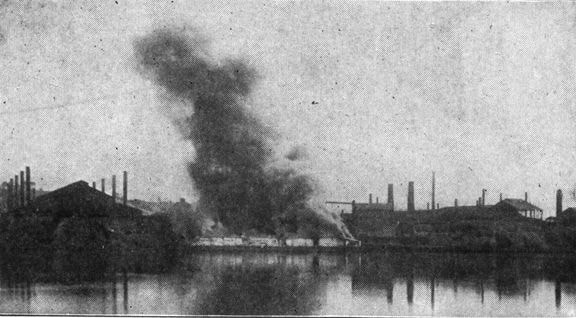

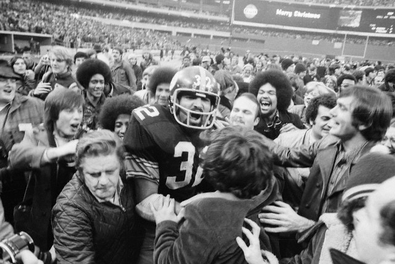

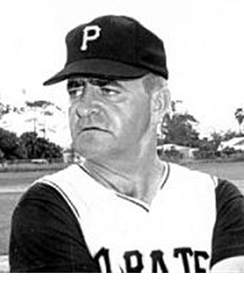

This hard quality came down the line from early times when Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia comprised the country’s hillbilly frontier territory of independent farmers, and then later, miners and factory workers. Pittsburgh was the location of the 1791 Whisky Rebellion, the first instance in U.S. history where working folks tried to push back against the financial class. Later, in 1892, the Homestead section of town was the scene of a seminal labor fight, when a rag tag band of workers went on strike to protest a twenty percent wage cut. They took up arms against strikebreakers and thugs hired by Andrew Carnegie and William Clay Frick. The strike was eventually broken by 8,000 state militia who marched into Homestead and reestablished order. Nothing encapsulates Pittsburgh working pride more than football and hockey. They were real blood sports back in the 70s—violent, tribal and unforgiving. The Penguins, called the Pens, played in the domed Civic Arena, known as the Igloo. Hockey was popular, especially because of the vicious on-ice brawls that were common in that era. But in Pittsburgh, football is king--Steelers football especially. You know you are talking with a real homegrown Steeler fan if you hear that raspy accent that turns steelers into “stillers.” The city of Pittsburgh suffered through decades of really bad Steeler teams all the way back to the early 1930s when the team was founded by a northside Irishman named Art Rooney. He was raised above his dad’s saloon, and was something of a neighborhood fixer and gambler. He paid the franchise fee for the team with race track winnings. Three years later, he had a legendary 3-day winning streak at Yonkers and Saratoga in New York, hitting a big parlay and five longshots among 11 straight winners. It’s a streak that remains one of the greatest horse betting feats of all time. The hundreds of thousands of dollars he cleared financed the team through many subsequent lean years. Rooney, affectionately known as “the Chief,” was an iconic, beloved character with his trademark cigar and shock of white hair. Late in his life, his faith in the chronically under performing team was finally rewarded. Uncle Ray was big Steelers fan. Every so often he would take us to a game, and it was like Christmas morning in our world. I can’t emphasize enough how big a deal this was. We had no means to go to these games. They were always sold out and there was no such thing as StubHub. The anticipation was unbearable as we'd pile into his big Cadillac, stop at a neighborhood deli for hoagies, then he'd steer through the ratty streets of the North Side, past the hustlers and ticket scalpers and winos, toward the concrete Mecca of Three Rivers Stadium. His season tickets were in the second to last row at the very top of the circular colossus. He knew all the folks sitting around him. There were thermoses of cocoa passed around and, of course, people were swilling Iron City beer. There were those big winter coats with the fur lined hoods. We sat through some really cold games watching the black and gold Steelers on the artificial turf way down below. Then one year, as his business thrived, Ray moved from those seats to a luxury suite with a kitchen in it and a whole deluxe furnished setup. That move tracked with the ascendance of the team into their dynasty years of the 1970s. The singular event that birthed the Steeler dynasty was the Immaculate Reception in ‘72, an improbable last second turn of events against the Raiders in the playoffs. It was so named because of such a lucky carom of the football people thought it could only have been divine intervention. The exact spot where it happened is marked in the parking lot next to the new stadium. The hero of that play was Franco Harris. Franco is a mild mannered African American dude with a beard and big afro. But he is also half Italian. So the the paesanos in the Italian community, the big old ball buster dagos who sometimes slurred blacks as “eggplants” embraced this guy. They formed Franco’s Italian Army, complete with combat helmets and tri-color Italian flags. They’d hold up this iconic sign in the crowd that read “Run Paesano Run.” In a town still self segregated by race and ethnicity, Franco’s Italian Army was a novel cross ethnic thing.  Myron Cope Myron Cope

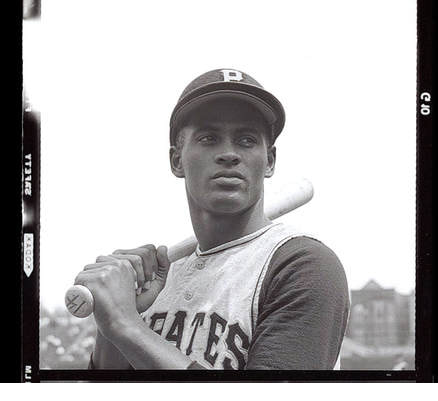

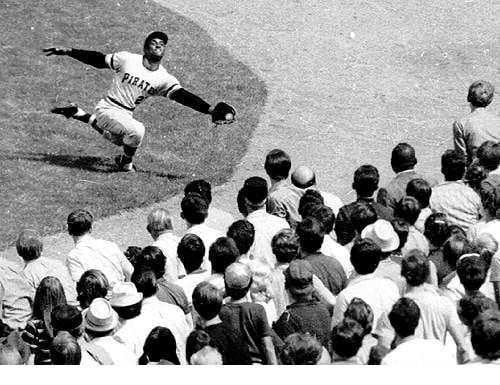

Historical footnote: Broadcaster Myron Cope is credited with naming the Immaculate Reception. He also invented the now ubiquitous Terrible Towel. Cope was an excitable little guy in a loud checkered sport coat, with a hard edged Pittsburgh accent, a distinctive nasal vocal delivery not unlike a local version of Howard Cosell. Today, watch any Steeler home game and you’ll see a stadium full of these yellow rally towels waving madly. Despite Uncle Ray’s improved seating fortunes at the stadium, I like to remember him way up in the upper deck, living and dying with his team, back when Terry Bradshaw was battling former Notre Dame quarterback Terry Hanratty for the starting job, and Mean Joe Green was just establishing the Steel Curtain, what would become the most dominant defense in the history of the sport. On the day of the first Steelers Super Bowl, Mom cooked grandma’s recipe for meatloaf, a fairly typical recipe made from a third each ground beef, pork and veal, with diced pepper, onion and celery. She’d coat the outside of the loaf with Heinz Chili Sauce, a ketchup-like condiment, but more spicy. They beat the Vikings that day, after which the team played in three more Super Bowls over the next five years. Each time, we boys insisted that mom make that same meatloaf. And they won all three. We concluded that Mom’s Super Bowl Meatloaf (Page XX) was undefeated at 4-0! In the mid-90s we tried to recreate mom’s magic out in California, but the Steelers (and our meatloaf) were defeated by the Cowboys. Like all kids across the city, we idolized the great Pirates right fielder Roberto Clemente. He grew up in the poor sugar cane fields of Puerto Rico and was one of the early Latino players to break into the big leagues back in the mid 1950s. He was a five-tool player who routinely cut down runners with his cannon arm and made impossible catches at the wall. Any mention of the Pirates of our youth begins with him.

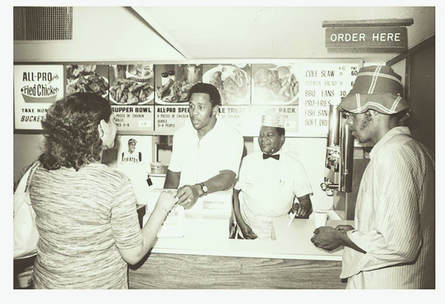

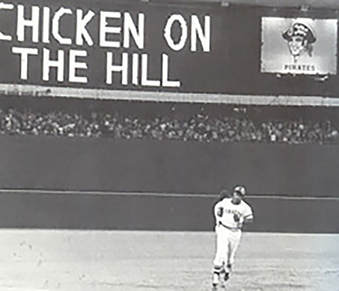

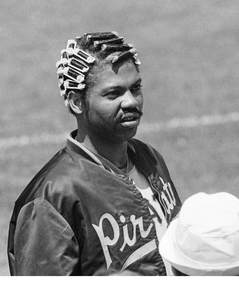

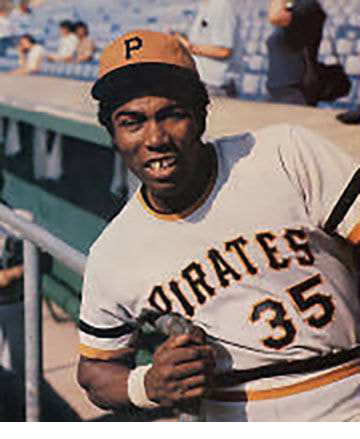

The Pirates are affectionately known as the Bucs or Buccos, short for buccaneers. We listened to Bob Prince, “The Gunner,” on KDKA radio. His gravelly voiced, homespun narrative was the soundtrack to many a summer evening, peppered with so many great nicknames and signature calls. Games were only occasionally televised, so there was always a transistor radio nearby with the staticy play-by-play going in the background. One famous Prince call was Chicken on the Hill with Will (Page XX). According to legend, it originated as a spontaneous promise he made on the air, that if Willie Stargell homered everyone inside Stargell’s fried chicken joint would get free chicken. The restaurant was in the Hill District, a neighborhood of row houses that was the center of black culture in the city. It had been home to the renowned jazz joint, the Crawford Club, a regular stop for luminaries including Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Lena Horne, John Coltrane and Charles Mingus. By the 70s the Hill was plagued with crime, junkies and boarded up buildings. We kids feared Hill District in the manner of urban legend, and never dared go through it. Willie Stargell did homer that night, and the restaurant was mobbed. It remains unclear who paid the bill or if the offer continued—but the saying lived on as Prince’s home run call whenever Willie went deep. Price told long, rambling stories, including episodes and hijinks with the team on the road. That Pirates team reflected the funky, soulful vibe of the early 70s. It was a team full of memorable personalities: the magnanimous, power-hitting Stargell; the ever smiling Panamanian catcher Manny Sanguillén; manager Danny Murtaugh, an old Irish cogger; and militant, corn row wearing Dock Ellis. Ellis owns one of the most bizarre feats in the history of the game, having thrown a no-hitter while tripping on acid. He was an outspoken critic of racism he saw that persisted in the game of baseball. This didn't sit well with the establishment powers within the sport. A little known side note is that when Ellis was under attack in the press for his combative attitude, the immortal Jackie Robinson himself sent him a personal letter of support and advice. In 71, the team had the distinction of fielding the first all-black starting lineup in Majors history.  Clemente Clemente

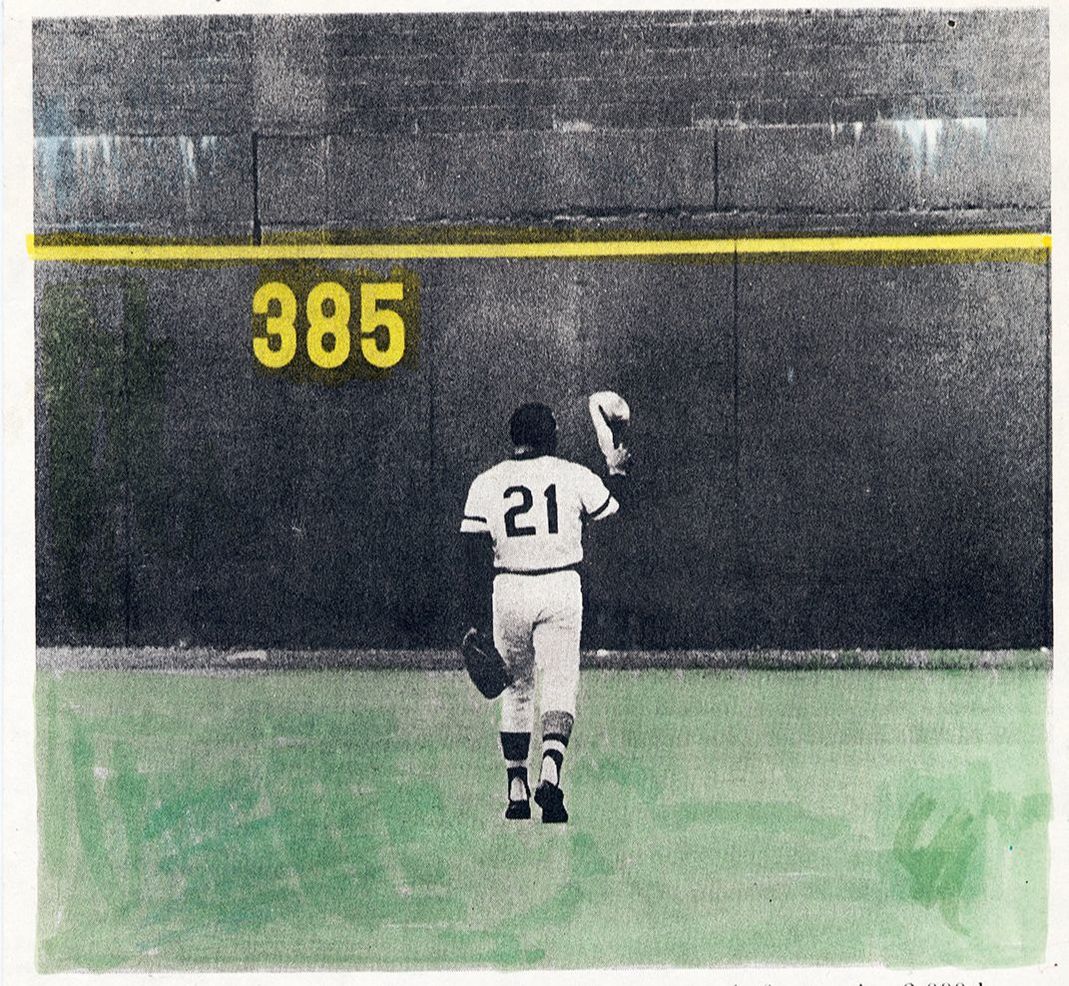

Clemente was the soft spoken leader of this swaggering ball club that won the World Series in 71. He had a haunted elegance and a quiet intensity. Teammates and opponents alike sensed they were in the presence of greatness. Others misread the distant persona as arrogance. The elaborate ritual of Clemente taking the batter’s box was mimicked in sandlots and wiffle ball games all over town: the handful of dirt, the neck and back gyrations, the deliberate sequence of precise adjustments. And then that off-balance reaching swing was so wrong according to hitting orthodoxy, but so effective and memorable. He played with a reckless abandon. His compact body had a certain indescribable quality to it, flailing, but with a self contained sort of grace and nobility. By the time I saw him play in person, in 1972, his legend was well established, and he had won over the tough blue collar town. The neighborhood paesanos in the first base grandstand that night sat in awe of Clemente. All evening we watched number 21 pad across the artificial turf under the lights. He seemed misplaced in the modernist concrete of Three Rivers Stadium, occupying his lonesome spot in the faded green reaches of right field. It would be his final season. Clemente was killed while on a humanitarian mission to earthquake-stricken Nicaragua. The old DC-9 plane he overloaded with food and supplies crashed into the sea right after take off from San Juan Puerto Rico. His tragic death crushed the city, and people all over the world. He left an indelible mark on a whole generation, and remains to this day a sacred icon in the Pittsburgh mythology.

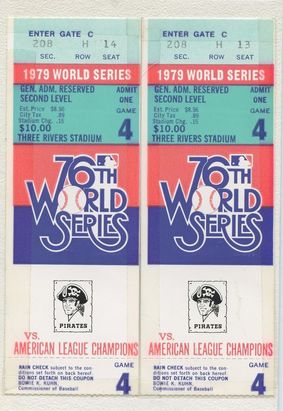

We were entranced by baseball and the Pirates throughout the 70s, culminating in the 1979 championship season. I spent that summer riding the bus down to the stadium, buying $2.50 upper deck outfield seats, but then sneaking into box seats, and exploring the bowels and catacombs of the stadium with bands of other stray, delinquent kids. That year is remembered as big-hearted Willie Stargell’s magnum opus, and also for the team’s stovepipe vintage caps—an oddity in the annals of Major League fashion. When they made it to the World Series I waited in line and purchased, with my meager teenage funds, two tickets to game 4 for me and my dad. He wasn’t a ball fan, but over the years he was a good sport about sitting through games and playing catch in the park. The Pirates lost that game, leaving the series at 3-1 in favor of Baltimore. An impossible predicament. We walked down long concrete ramps and out of the stadium with the deflated crowd. Owing to my dad’s extreme frugality we had parked in a North Side neighborhood, blocks and blocks from the stadium, up past the old Clark Bar candy factory. That was a solemn march. On the drive home I teared up, one of the very few times any kind of emotion came into our stoic relationship. My dad said a few sympathetic things but mostly stayed quiet. Somehow that car ride home is one of the nice memories I have of me and my dad. The deep despair of Game 4 set up an unlikely comeback. The Pirates, rallying around the disco song ‘We Are Family,’ ended up winning three straight to take the Series. And in Baltimore some other kid was crying. |

|

© Copyright Confluence Studio. All rights reserved.

|