Finding Nigel

PART 1 — A Memory Care Story

|

Justin Panson

At 91 years old, our dad lives alone in a third story walk-up condo on Grandview Avenue, a place with a spectacular view of the city of Pittsburgh. In his windows the Monongahela River flows right-to-left into the Ohio. Long coal barges push through the murky water under old railroad trestles just like they did a hundred years ago. Beyond the river, the skyline rises, a mix of industrial age buildings and modern glass-plated towers. Dad has lived here since the late 1980s. He bought the place, he said once, because he needed something to make himself feel better as he was coming off his second divorce. You become transfixed by the view, especially at dusk as the old rust belt metropolis slowly, imperceptibly lights up. The twinkling vista has a quiet sort of drama about it. This place is so connected to our dad’s sense of identity—maybe like any place you’ve lived for several decades. And that’s what is making things really hard right now. The old man is in pretty good shape for 91. Although he is severely hunched over, he manages to trudge up those three flights of stairs, and swears that this climb keeps him in good shape. But my brothers and I have realized his time here is coming to an end. About a year ago we started to bring up the tricky subject with him, at first just generally suggesting he start to plan for the future. ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM Age-related things can be difficult to talk about. But there are three things that are making the conversation with our dad particularly hard: the first is that we all live far away from him. Two of us are in California and our third brother is in Denver. We left as part of a diaspora of Pittsburghers who moved west during the collapse of coal and steel in the 1980s. The second complicating factor is dad’s failing memory. “Memory Care” is the vaguely clinical term used in the senior industry. It’s not well understood by lay people—sort of a slippery slope encompassing dementia, alzhemiers, and the normal dulling of cognition in advanced age. Trying to tease apart the subtle differences between these concepts is difficult. Dad has good days and bad days, so it’s a hard thing to pin down. Several times last year we approached him with a logical case for our assistance with his affairs and future living arrangements. What we didn’t realize is that he was already too far gone to process our entreaties. On the phone he sounded mostly OK, but we were hearing only the generalized exterior of his former self. We were too polite or oblivious to realize what was already happening. The third challenge we face is Dad’s own vanity and pride around his sense of youthfulness, and as a result his denial of his own aging and mortality. All of his life he never played cards or golfed other things he saw as “old people stuff.” Until about five years ago, he was still skiing and riding his bike. All along, he got a lot of praise and attention for being so youthful. I suspect this sort of denial may be a common thing with his generation, and the boomers that followed, who have been nurtured on a sense of their own uniqueness and invincibility—that they would somehow live life differently than previous generations. As they are now discovering, you can’t outrun old age. To go one step deeper, there is a core American trait that ignores limits—more, bigger, better, faster—a gospel belief that the natural limits of the human condition somehow don’t apply to us. In the prime of life we convince ourselves of our own power and control. Money and technology reinforce this notion—we walk around with magic smartphones in our pockets that can solve any issue. This is illusionary. Eventually the universe will reassert its power, and we will be rudely squeezed out. In our prime we are likely incapable of contemplating our own decay, telling ourselves what we want to hear. The modern life arc itself is an artful fiction of positivity and hopefulness. When inevitable aging arrives, it can be a difficult reckoning. Our cultural unwillingness to address mortality, to instead celebrate a limitless culture of youth, is sort of like the elephant in the room writ large at this moment. The boomers are stacking up, moving en masse into the late stages of the life span. SELLING THE DREAM Indeed, the senior care industry has embraced the vanities around youthful living, and they are waiting for you with a lux experience carefully modulated to appeal to your natural affinity for “active” living. They offer an experience full of little perks and creature comforts. They promise an exclusive and painless end of life experience. We toured dad through several senior communities, took note of the amenities, asked good questions, considered the food service, and marvelled at the daily schedule of outings and activities. We dutifully logged all of this on a spreadsheet for consideration. Some of the higher end places require a substantial buy-in fee, like joining a country club. There are different levels of buy-in, and complexities around how those funds will be returned (if at all) upon the resident’s death.

The cost of senior living is high and climbs even higher as one progresses through the tiers, from independent living to skilled nursing. The good news for us is that over the years dad amassed quite a warchest, owing to sound investments and his extreme frugality. Like a lot of his depression era peers, he scrimped and saved to a ridiculous degree. One of the first things you notice is how nomenclature reveals motivation. Gone is the term “nursing home,” as that language says “waiting around to die.” It’s been replaced with “Senior Community,” where there will be friends and swimming pools and games, and you may even get laid. As my brother and I found out, the senior community salespeople are ready to sell you a dream of elegant and fun-filled golden years. To be fair, I have a tremendous respect for the people who work with seniors. They do the work that most of us couldn't do—washing and dressing other people, having great patience and a high tolerance for the nasty side of life. To a person, they seemed deeply dedicated to their work, and focused on providing great care. The conversations we had were empathetic and there was a sensitivity to our situation and to what would be best for dad. Prior to this, I didn't think much about senior care. I now realize it takes a special type of person to work in this field. LAUGHING SO WE DON’T HAVE TO CRY Managing dad’s transition has been challenging, but it has also had the unexpected effect of bringing my brother Andy and I closer together. Our tactical efforts have largely been successful, though we’ve worked through small setbacks. There have been visits to banks and lawyers and setting up in-home care and cracking into his accounts and trying to organize a real mess of his paperwork. We actually got very lucky, rolling into town just as dad was letting balls drop: bills going unpaid, a prostate surgery that wasn’t vetted or understood, a bathroom leak that went unattended and resulted in water damage to the unit below. It’s alarming to see normal life maintenance issues go unaddressed. My brother and I have formed a good team for getting things done. We are an odd couple: my personality is loose and energetic, perhaps a bit too chatty and emphatic. I am more comfortable with seat-of-the-pants operation. He is shrewd and reserved, with a really dry wit, excellent on the details and finances, a nervous, procedural guy who is managing an anxiety condition. In our efforts, there have been a handful of humorous anecdotes that, in hindsight, have helped lighten things up, and have reminded us that sometimes you just have to laugh in the face of a chaotic and absurd universe. THE ANXIETY ATTACK After much effort, we managed to crack dad’s email account, and that allowed us to perform several things related to his financial accounts. As Andy was completing a transfer of account ownership he accidentally hit the submit button with some incorrect info in place. “Shit!! We just got locked out!” This was a snafu that would end up setting us back and causing a bunch of additional work. He was pissed at himself, and then began to spiral into a panicked state, speculating aloud whether we would ever be able to gain control of the account. He was envisioning some sort of Kafkaesque bureaucratic nightmare—which is actually not far from the truth with many of these financial matters. I tried to reason with him, “We’ll straighten it out tomorrow on the phone.” He began to hyperventilate, and for some reason I started to unleash a torrent of swear words, I think using this tough act to signal that this was no big deal. My efforts had the opposite effect, and only made him more tense. At one point he said something like, “when you swear like that it makes me very uncomfortable when I’m in this state.” It was a little moment between us that we now laugh about.

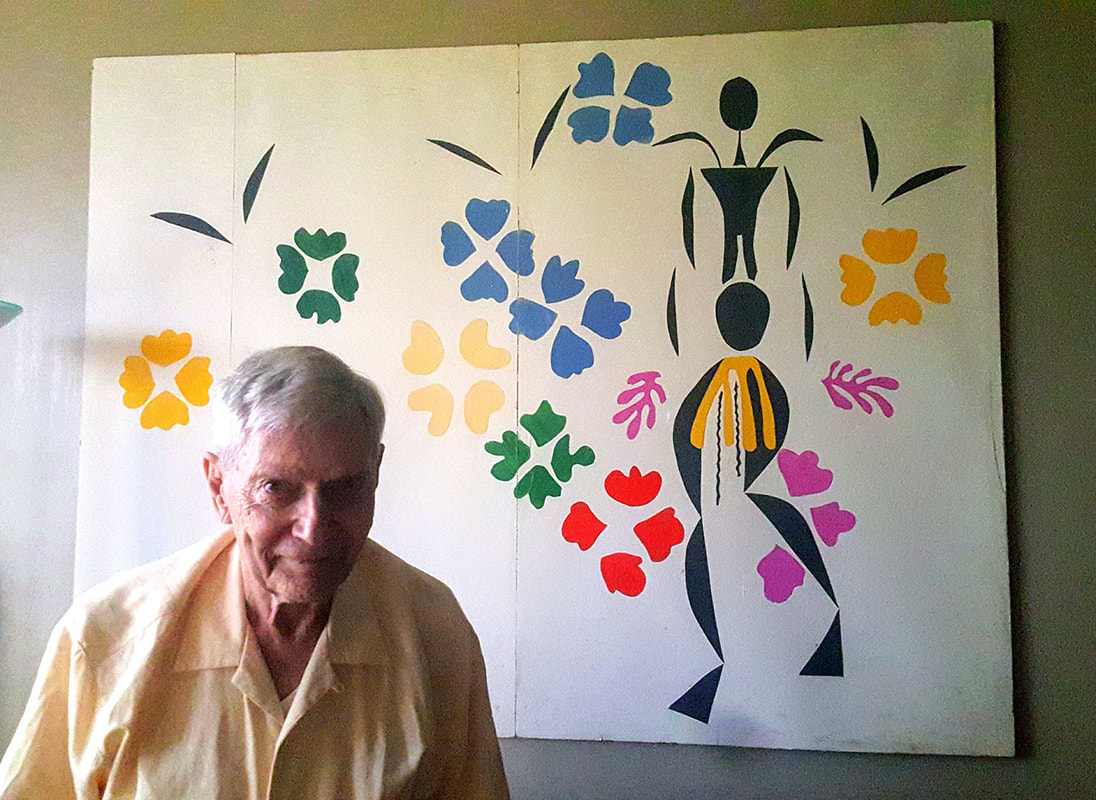

SHOPLIFTING AT THE STOP-N-ROB On our last day before heading back to California we realized dad hadn’t been doing laundry...and this was compounded by the fact that he had ongoing trouble managing his catheter. So his clothes and bedding all smelled like piss. We gathered everything up and headed for a laundromat where we could do a bunch of loads at the same time. The place was sketchy. There were dudes making drug deals, and several oddball characters loitering around. I ran across the street to the stop-n-shop to get a bottle of detergent. When I got back I realized the dead-eyed clerk had failed to give me the $5 discount that was advertised on the shelf. Maybe due to the stress of the whole visit, I just sort of snapped and became very agitated, vowing to go back to the store and shoplift at least five bucks worth of stuff. It was mildly amusing the first few times I said it, but then I became obsessed and increasingly pissed off at this clerk. “I’m going to fucking shoplift the hell out of that place...seriously...that inbred hillbilly bitch!” Andy was being reasonable, calling out the absurdity of shoplifting, trying to talk me off the ledge. The more reasonable he was, the more I wanted to just go agro. I eventually calmed down, however, I do reserve the right to shoplift that place the next time we go back! HOMELESS WITNESS AT THE NOTARY There was this memorable episode on the last day of our visit. We were jamming to get a large number of things done, including a quick stop at a law office in dad’s neighborhood to get a financial form notarized. We had contemplated that we might be short a witness, and sure enough when we got into the office we realized that was the case. I told the legal secretary to hold on and ducked outside. At that moment, there was a homeless guy fishing cans out of a trash bin on the sidewalk. I approached and asked him if he’d be a witness, if he had an ID. He did and turned out to be a really sweet guy who agreed. I offered him some money but he refused, saying his mom raised him to help out. He did take a ten-spot after I insisted that we at least buy his lunch. As we were waiting in the office, he launched into a story about his dad who he claimed was a pool hustler in the mob back in the 1950s. He claimed his dad had dealings with the famous Rooney family on the northside, the ones who own the Steelers. Sensing the unfolding absurdity of this situation, I prodded him to continue with the story. His details actually checked out based on what I know about Pittsburgh history. But then he took a tangent into the Gambino crime family, claiming that when he was just a kid Carlo Gambino would personally call him from New York to ask for his pro football picks. Then into J. Edger Hoover, and the Kennedy assasination, and Castro. The wheels were coming off. He claimed he had written a manuscript about all this inside stuff. The legal secretary looked askance at him and I kept him engaged, out of amusement and as a way to distract from the awkwardness of the moment. Dad was sitting there in a bit of a catatonic state. The absurdity of the scene was too perfect. NO PANTS We heard from dad’s in-home care people that one day he had answered the door forgetting to put on his pants. Now I’m not sure if that means underware...or no underwear at all. And I don’t really need to know that. Andy and I continue to share laughs about that, hoping the no-pants thing isn’t a family trait locked into our DNA. MEET NIGEL, OUR PHANTOM DESIGNER Of the places we toured, the one dad really like was called Schenley Gardens, a highrise in the university section of Pittsburgh, with a very nice corner apartment available. The clinching factor was that this apartment had sweeping views of the surrounding neighborhoods. He liked it because it reminded him of his place overlooking the city. All went well, and he passed the financial assessment as well as the medical assessment. We were just waiting for a confirmed move-in date. So the subject turned to furnishing the apartment—how much current furniture to bring verses what things to buy new? Dad wanted a fresh start, which was good since much of his apartment smelled like piss. We said we would help him pick out things from IKEA. The Scandinavian minimalism was aligned with dad’s lifelong tastes, and IKEA offered us a logistically easy way to go...since the move-in and related tasks was going to be like threading a needle in the timespan of a weeklong visit. A few days later, dad called and indicated that he didn’t want to leave the furnishing decisions to “a bunch of amateurs.” He wanted a “professional” interior designer. That idea alone is not outrageous, but given the tight window of time, the many other balls we had in the air and the need to do much of this from remote, it was kind of absurd. At one point on an email thread we three brothers began to speculate on the advantages of inventing a fictitious interior designer for the purpose of satisfying the old man’s request...and expediting the move-in. We began to add details. Andy’s wife suggested maybe he should be Nigel, a flamboyant gay British decorator. Mike thought of a Swiss guy named Bertolt with a set of highly eccentric requirements before he could be engaged. Nigel as a concept has taken on a life of his own—because staying mildly amused is preferable to being overcome by a sad situation. Nigel actually provides an old man one final bit of control, one last taste of the heady good life where one might engage a designer. I imagine Nigel is bold and decisive. He is unafraid of contrary opinions. He is a breath of fresh air in this situation. In a way, we all wish we could sweep in with excellent solutions, like Nigel. For me, this invented persona has come to represent our efforts to retain some sense of honor and dignity for our dad, even as we execute a set of decisions that will ultimately be the dismantling of his autonomy. FINDING DAD In a way, finding Nigel is really about finding my own dad—a son trying to understand his old man, a son revisiting the family history that he’s told himself all these years...a son realizing how that family history fails to capture his dad’s real story. “Dean took out other pictures. I realized these were all the snapshots which our children would look at someday with wonder, thinking their parents had lived smooth, well-ordered, stabilized-within-the-photo lives and got up in the morning to walk proudly on the sidewalks of life, never dreaming the raggedy madness and riot of our actual lives….” —Jack Kerouac, On the Road At one point I looked at dad and saw this pathetic vision of the man—his back severely bent, his catheter leaking on his khakis—and I didn’t recognize him. When we talk with dad now, we slow down our speech, like talking to a child. These days it’s hard to remember that he was an accomplished man who built a nice life for himself. The framework of his biography speaks to these accomplishments: He grew up in New England, son of Polish jews who were in the textile business. They moved to Brooklyn and he attended the prestigious Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan. Army at 17. PhD. on the GI Bill, awarded seven patents while at Westinghouse Research where he worked for 40 years, married a pretty woman who was a fellow chemist. In those early married years they went hiking, skiing, sailing and canoeing with a crew of young adventurers. He travelled widely, liked art museums, the symphony, opera and literature, as the shelves of books in his apartment attest. Then three kids, then the big brick house. He made wine and flew airplanes. On and on. But of course, I have lived with this skeleton biography for years, and I now realize that I never really knew my dad...and never will. A FLAWED MAN LOOKS OVER HIS SHOULDER What usually has the strongest psychic effect on the child is the life which the parents have not lived. —Carl Jung This story is about a son coming to terms with his dad’s flaws, in this case that he never learned how to truly express love for other people. He was a four-time loser in love, and had only cursory relationships with his sons. He wasn’t able to get out of his head to have the type of empathy and interaction that builds lifelong bonds. Maybe based on his profession, he’s a guy bound up in a sort of scientific neutrality, for whom emotional things don’t come easily. That all sounds awfully harsh, doesn’t it? Maybe there are always insurmountable generational barriers between parents and children no matter how close they are. In my younger years I resented his inaccessibility, didn’t understand it. I am trying to be more generous now. Through this process I have come to the idea that we are all flawed—something I was not able to previously see. Maybe the finality of dad’s aging has triggered my evolution, maybe it’s because of where I am in my own life: middle aged, working on my own issues, trying to take a different path than he took in love and family things. Circle of life. People tell themselves a story about their own lives, which may or may not add up to a pleasing tale. In my 50s I am entering the first part of becoming “old,” when you start to become invisible—the cool younger people seem to look right through you. The cultural references and new celebrities are lost on you, and the world begins to look less familiar. At best, we chuckle politely at our own irrelevance, or we retrench back into a nostalgia for things from our formative years, as in the surprising longevity of Classic Rock. The idea that somehow I may do things differently than my dad is a nice thought, but to be fair, he faced his own challenges, made his own decisions and has lived with them. There's just a bit of hubris in a mid-50s guy judging a 90-year-old. Talk is cheap when you’re in good health in your prime. We’ll see how cavalier I am in a few decades, when my vanities and conceits come into sharp focus for my kids...and they may have the need to invent their own Nigel. Until then, we three brothers are dedicated to guiding dad as gracefully as possible into the final chapter of his story. 2020 Love After Love By Derek Walcott The time will come when, with elation, you will greet yourself arriving at your own door, in your own mirror, and each will smile at the other’s welcome, and say, sit here. Eat. You will love again the stranger who was your self. Give wine. Give bread. Give back your heart to itself, to the stranger who has loved you all your life, whom you ignored for another, who knows you by heart. Take down the love letters from the bookshelf, the photographs, the desperate notes, peel your own image from the mirror. Sit. Feast on your life. |

|

© Copyright Confluence Studio. All rights reserved.

|