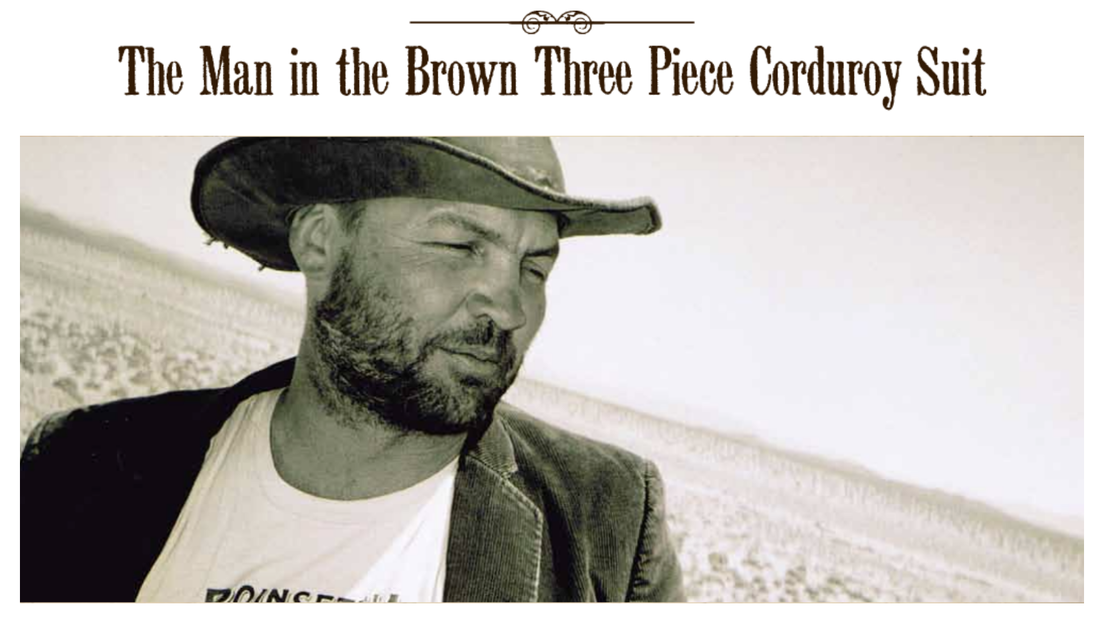

CALAMITY TOURIST, ACT II

Avalanche on Mt. Tallac, 2005

|

Justin Panson

There are few activities more readymade for calamity than mountain climbing. In addition to the topographical danger, there’s the vain, self-involved nature of the pursuit. Plodding to the top of a harsh peak just so you can say you did it. The plot elements are common to the point of cliche—unseen mistakes, ill advised decisions, headstrong people blindly focused on a summit trophy. If we’re trafficking in a cliched genre, might as well throw in a mock heroic line like “The mountain was angry that day, my friend!” — spoken by some wizened old trekker in a cozy lodge spinning a tale of snowy peril. But there is no mythical dude like that, no cozy lodge. Just a guy who toils in mundane cubicleland and drives the same highway commute everyday. Even this cubicle guy has a few tales he carries around like currency from another era. Yes, that day we city guys did blunder unawares into snowy peril. April Hike Plan My friend Michael Preston and his younger half brother Tommy had come down to Sacramento from Arcadia in far Northern California. They were novice mountain climbers with unrealistic aspirations to climb McKinley up in Alaska. I knew these guys through a circle of midtown folks who liked to camp out in certain remote Nevada ghost towns. This group was an oddball collection of eccentrics, artists and lovers of western lore. Preston knew I liked to snow climb the peaks in the Desolation Wilderness near Lake Tahoe. He started asking me for information, and I agreed to take them up Mt. Tallac. Preston is a big hearted lug of a guy, larger than life, and comically absurd in his giant enthusiasms, and possessed of a true blue, old school sincerity. He came out west from rural Ohio and joined the navy, working as an engineer on nuclear subs. He’d weave in all kinds of old navy sayings and wit. Preston was a physical specimen, bearded and as is said, “strong as ox.” He distinguished himself with many feats of strength and endurance in landscaping and construction and in climbing Party Mountain. His half brother Tommy, affectionately called Lamb Bottom by Preston, was a nice, sincere kid maybe ten years younger than Preston. At the time, Tommy was working some menial gig trying to get into a local community college. I had a soft spot for the way Preston’s paternal affection for Tommy was kind of woven in between all the macho banter. Preston would counsel him to stay focused on school. It was mid-April, the time when I had usually climbed Tallac, a starter peak, done to prep for Shasta or Whitney. There had been heavy snow that year, so we rented snow shoes, which I didn’t typically use. Preston and Tommy also rented crampons and the straight glacier travel ice axes. They came down and stayed with some other friends. As Preston was such a big partier, I had to really stress to him not to drink the night before. Though only a smaller peak, that altitude was not to be messed with. Roadtrip Omens They came by my place very early Sunday morning, with day packs and gear, ready to go. And the three of us took off in my SUV as the sun was coming up. I’m not a superstitious guy, but on the two hour trip east up to Tahoe two omens showed themselves. Had I been more tuned to these supernatural warnings I might have turned around and gone back to bed. Just out of town and passing through Folsom, we rounded a bend in the freeway and saw a car engulfed in flames on the side of the road. There was nobody around at all. Did we actually see that? It was just the most surreal scene. We blew right by, like it was only a dream and didn’t stop or call it in. We looked at each other as if to ask, was that real? By the time we processed the image, we were a quarter mile down the road. And kept on going. Further along, as we started climbing into the Sierra foothills, Preston began loudly and clumsily going through the contents of his pack, that he had wedged in the front seat with him. He pulled out a box printed with techie looking graphics. “The JetBoil 5000!” he proclaimed proudly, and opened the box, pulling out an aluminum cylinder. He had gone out and bought a bunch of gear for this hike. He began reading the marketing pamphlet included with this backpacking stove. I tried to explain that on this one-day climb we wouldn’t be stopping long enough to cook a hot meal. He wasn’t paying attention, but instead read the blurbs on the packaging. “Hey, check this out: “commuters can use this to make coffee in their cars.” Before I could figure out where this was heading, Preston was well into the procedures for lighting the stove. He flicked a lighter and poof, the thing flamed up wildly, licking the headliner in my truck. “Goddamnit Preston! Put that thing out.” He apologized profusely and made a show of dusting off the headliner, on which I did notice a few singe marks. As we dropped down from Echo Summit into South Lake Tahoe we spied the silhouette of Mt. Tallac off to the west. Tallac is just under 10K feet, and rises from the west bank of Fallen Leaf Lake. It is a classically jagged peak coming to a nice point when viewed from certain angles. Because of its perch beside Tahoe, the views from the top are sweeping, and encompass the lake and the Desolation Wilderness to the west. Confidence & Risk Near Baldwin Beach we turned onto the single lane road up to the trailhead, but had to park and snowshoe in about a mile to get to the trailhead. This should have been the first sign that there was way more snow on the mountain than usual. I briefly considered the decision to proceed, given the amount of snow. The typical climber is a fitness cultist with tribal identification around REI-purchased gear and high-end mountaineering brands. As I looked at Preston tromping the first steps of the hike, what I saw was quite the opposite of this—an old school dude lumbering through the snow like some kind of roughneck from the pages of history. At this decision point with the trailhead snowed in, I had fallen for a “heuristic trap,” a trap of confidence. The phrase is from a 2002 paper by Ian McCammon, who sought to explain why avalanches are often triggered by knowledgeable backcountry skiers who should know better. Their experience actually hurts some skiers, the author argued, by making them overconfident and willing to disregard ordinary safety precautions. He listed common heuristic traps that lead to avalanche fatalities: doing what is familiar; being committed to a goal, identity, or belief; following an “expert”; showing off when others are watching; competing for fresh powder; and seeking to be accepted by a group. Having a healthy respect for nature is a key tenant to survival. Perseverance is rewarded on the mountain right up until the point where it is penalized. What we have tried to do is to put into place a pretty good set of habits…we always have each other in sight…we stay within shouting distance. We also have to have a pact between us that we go with the more conservative judgment. Risk is a funny thing because it stems from an Italian word, rischio, meaning to dare, and that implies both opportunity and choice. But if we take on these risks and we treat them like games of chance, then we’re just shaping our fate. We’re a very fickle society when it comes to risk because we celebrate it when it succeeds and we denigrate it when it doesn’t—like, ‘oh, those people were being so reckless.’ We all take risks, but the key is to understand the risk that you’re taking. — Jill Fredson Mind Tricks, Up the Gut As was my custom on this hike, we turned off the trail and straight up the steep eastern face, through what is known as the Iron Cross or up the chute just to the south of it. This approach gives you an alpine feel you don’t get on the trail that wraps more gradually around the back side and then up the ridge. “We’re goin’ up the gut,” I said, and Preston liked that very much. There is an appeal to this approach. The grind, the isolation of effort, the physical element. On this steep section my friends got their first taste of grinding out just a few steps and a time and then having to catch your breath, and the “front pointing” technique of kicking the front spikes of your boots in with each step to get purchase in the snow. As we went up the chute I noticed the cornices, or snow overhangs, were heavy. Another clue I ignored. On this kind of steep ascent, some days you feel strong, making distance quickly with big steps. Other days it is really hard and you're going back and forth in your mind, battling with the idea of quitting. Some days you just get beat and give up. Like a lot of sports, it’s a mental game, staying encouraged when you want to give up. One time up on Shasta with my friend Reginato we got to Misery Hill and were really tired from having to high kick in thick wet heavy snow. We had to mind-trick ourselves. The more official term might be “intermediate goal setting,” where you pick out a spot in the near-distance and focus only on getting there...and then another one. This was probably the only thing that prevented us from folding up and heading back down. “You also need to turn around negative thoughts, as these will visit you the more knackered you are. Thoughts play on emotion. They can appeal to your common sense by reminding you to cut your losses and turn around, to your pride by telling you that you don't need to prove anything to anyone, or your sense of self-preservation by reminding you how tired, hungry, cold, and thirsty you are. — Vanessa O’Brien, mountaineer, First American/British woman to summit K2 |

Dreamscape in the Sky

The reason I like climbing is the feeling on top, the sublime feeling of being way up high. Hard to describe. You’re a little light headed and spent. On Shasta and higher peaks it can seem like a beautiful dreamscape due to the slightly dizzy feeling you get from less oxygen in the air, and when it’s overcast, the whiteness enhances this feeling somehow. When it’s clear you are seeing mind-blowing vistas spread out before you, the wide distance so far below. A feeling of awe that is antithetical to talk about “bagging peaks” in a transactional way. To be out in the cold and snow, and step-by-step ascend into the thin air. My experience and connection to climbing is about seeking the higher ground—altitude and a transcendent experience.

Ramble to the summit of Mount Hoffman, eleven thousand feet high, the highest point in life's journey my feet have yet touched. And what glorious landscapes are about me, new plants, new animals, new crystals, and multitudes of new mountains far higher than Hoffman, towering in glorious array along the axis of the range, serene, majestic, snow-laden, sun-drenched, vast domes and ridges shining below them, forests, lakes and meadows in the hollows, the pure blue bell-flower sky brooding them all—a glory day of admission into a new realm of wonders as if Nature had wooingly whispered, 'Come higher.' — John Muir

On this day we could see Lake Tahoe, and to the west the Desolation Wilderness peaks. But it was less of a dreamscape and more of a frigid, nasty hell of strong wind gales that were literally blowing 230+ pound guys off our feet. We stayed up on the summit only a few minutes, forgoing the normal lunch and snapshots. We just wanted to retreat back down out of the high wind.

Tremendous Machine of Snow

I had marked the chute we came up with a branch, which I located. We picked our way carefully down a very steep couple hundred yards. When we got further down to the last big bowl, the guys were anxious to try glacading, a fancy French word for sliding down on your ass, using the axe as a break. It’s fun, and when you’re tired it’s a quick way to cover a lot of ground. You do have to be careful as your speed can get away from you and you can lose control. They bombed down the bowl with gusto and I followed along more slowly, tracking them maybe 100 yards down the mountain.

The saying goes “Mountain climbing is extended periods of intense boredom, interrupted by occasional moments of sheer terror.” All at once I saw a giant ripple of snow shoot up the bowl very fast. It was the mountain collapsing in a chain reaction. In the movie Alien the line was “In space no one can hear you scream,” and in an avalanche no one can hear you scream either. But I yelled “Avalanche” anyway, reflexively. There was a rumbling sound and then in an instant I was trying to swim, to stay on top of it. But I was churned into it and hurtled down. I went into a tuck, no longer in control, just tumbling with my eyes closed, and I had the thought that this is how it ends, slamming into a tree or rock. It’s surprising how quickly you process the idea of your own death like that.

It seemed like it wouldn't stop. It’s hard to reconstruct the timing. Was it 15 seconds, 30? Maybe a hundred yards or more. And then all at once it seemed to slow and came to a stop. And I could see Sunlight about only a foot above. I was able to wiggle out. I was staggering around and spotted Preston and Tommy walking back up about 50 yards calling for me. I couldn’t get my breath and the burn from the ice was intense over my whole body. The stinging of the snow scrape was unbearable and my legs were cramping badly. Eventually I got control and then we all were just trying to process the power of what just happened. Preston and Tommy had been knocked down but didn’t have the ride I did. We looked back up the bowl and a 200 x200 yard chuck was missing.

“It’s light and fluffy and soft and downy, and it’s everybody’s favorite thing in the world. It’s also one of the most destructive forces in nature. Under the right conditions, that soft, wonderful little snowflake can tear forests out of the ground, throw cars through the air, flatten buildings. And you get to watch that.” — Dave Richards, the head of Alta’s avalanche program, Snow Science Against the Avalanche

The mechanics of a slab avalanche are where top layers of snow break away from the bottom layers, and “tens of thousands of tons of snow accelerate from zero to 80 miles per hour in five seconds, obliterating pretty much everything but rock. Their violence boggles the human mind.

The way a slab avalanche works, you in fact trigger a weak layer of snow hidden under the surface. ‘It's buried below the more cohesive and denser snow slab, so it's really like a sandwich,’ says snow physicist Johan Gaume, of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, who developed the simulation. ‘You have this weak layer, it's very fragile. It's like a house of cards, basically.’” — Matt Simon, WIRED Magazine

More info on the science of avalanches

In the slow motion of hindsight I keep seeing this image of someone just disappearing into the white, sinking and drowning, pulled down into the snowy depths of mythology by some nordic troll who snatches glacier travelers.

Retreat from the Backcountry

I checked my limbs for injuries, taking stock of what gear we had. I had my pack but I lost my snow shoes, axe and cap, which I didn't look for. We were in a fear mode and had an overwhelming need to get down below the treeline fast. We hiked down and into the trees, picking our way past Floating Island Lake, covered in snow, and eventually found the trail.

Lower down we stopped to rest and Preston did an inventory of his pack, pulling out the JetBoil 5000 and a crushed Cup-A-Noodles that he comically regarded, with still a half mind to try to put his gadget to use. When we got back into cell coverage, he made a call. I could overhear him saying, “Skiing is for pussys, we just rode an avalanche!” At the time, this was sort of disturbing to me as I was pretty rattled.

Bravado & Reckoning

There's bravado and then there is reckoning—we didn’t get back to town until late, and on the return I had to make a difficult phone call to tell my wife. The next day I ended up in the hospital with cardiac episode symptoms, which turned out to be some internal injuries I had sustained.

Within a few days there was an email from Preston containing a link to an article that appeared Monday in the local South Lake Tahoe newspaper. The ominous headline: Massive Slides on Tallac. The avalanche we triggered was memorialized in print: https://www.tahoedailytribune.com/news/massive-slides-on-tallac-mark-spring-avalanche-conditions/

Later in the summer I got a random call from the El Dorado County sheriff who found REI rental snowshoes and traced the number to us. He asked if everyone was OK. The next year we three climbed Mount Shasta, the 14,000 foot pinnacle of northern California mountaineering. That epic 14-hour slog culminated in the Preston Wedding Ring Toss Story (in the chapter called "Man in the Brown Three Piece Corduroy Suit"). The combination of Preston and mountaineering again yielded drama.

17 years later this avalanche story has clarified into a handful of themes. It’s about risk and bad decisions, the ambition and hubris that drives weekend warriors like me out to the backcountry and into near casualty situations. It’s about nature enthusiasts and the joyful misery of grinding up steep snow chutes. And it’s about the bonhomie of climbing with your crazy buddies—the wildman Michael Preston, and the omens he may have brought with him to Mt. Tallac.

2022

*************************************

“I am losing precious days. I am degenerating into a machine for making money. I am learning nothing in this trivial world of men. I must break away and get out into the mountains to learn the news.”

― John Muir

“A man who keeps company with glaciers comes to feel tolerably insignificant by and by. The Alps and the glaciers together are able to take every bit of conceit out of a man and reduce his self-importance to zero if he will only remain within the influence of their sublime presence long

enough to give it a fair and reasonable chance to do its work.”

– Mark Twain, A Tramp Abroad

No feature, however, of all the noble landscape as seen from here seems more wonderful than the Cathedral itself, a temple displaying Nature's best masonry and sermons in stone. How often I have gazed at it from the tops of hills and ridges, and through openings in the forests on my many short excursions, devoutly wondering, admiring, longing! This I may say is the first time I have been at church in California, led here at last, every door graciously opened for the poor lonely worshiper. In our best times everything turns into religion, all the world seems a church and the mountains altars. And lo, here at last in front of the Cathedral is blessed cassiope, ringing her thousands of sweet-toned bells, the sweetest church music I ever enjoyed. Listening, admiring, until late in the afternoon I compelled myself to hasten away....

― John Muir

|

© Copyright Confluence Studio. All rights reserved.

|