The shadow creeps and creeps, and is always looking over the shoulder of sunshine.

~Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1851

~Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1851

Would you believe me if I told you a story about hidden gold in the old west? A true story that I heard from my hundred-year-old grandfather back in 1960? This is a tale that is verified by a physical object that he stole from a dead man’s hand. But I am getting ahead of myself.

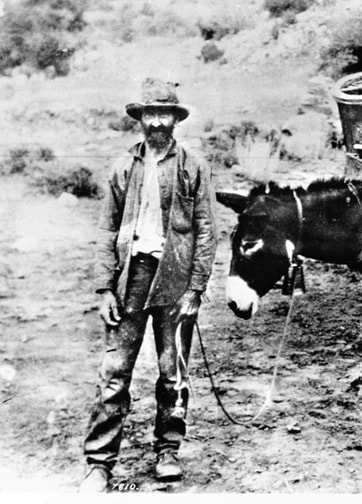

We visited my grandfather quite a lot near the end of his life. He lived near us in Dayton, Ohio, in an old stone, gothic institution that had been converted into a nursing home. We didn’t like going there. The deformities and freakishness of old age were on full display. Our family would sit around his room making small talk, awkwardly passing around the chocolates we had brought. On one such occasion, when my parents had left to meet with the doctors, my grandfather told me the story of Orson Grisby—this fantastic tale about a washed up old Gold Rush prospector who he had actually met. According to my grandfather, Grisby had come out to California in 1850 from St. Louis along with tens of thousands of other hopeful souls from around the world. He spent two decades living in wood shanties, boarding houses and tents all over the rugged hills of the Sierra Nevada. He had drifted through a string of several ventures, claims and partnerships, none of which had amounted to much. By 1870, he was bunking in the drafty store room of an outfitter on Main Street, three doors down from the famous hangman’s tree of Placerville.

Grisby was one of many eccentric figures in that hill town full of pioneer characters—miners, tradesmen, merchants, gamblers, and ladies of dubious profession. A man of small stature and advancing years, he was a picture of what you would imagine a ‘prospector’ to be, with a scraggly gray beard, worn trousers, suspenders, sack coat, all topped with a floppy wide-brimmed slouch hat. Grisby was a weathered specimen, owing to a pursuit that ground men down in a matter of years, yet his eyes remained bright and he had a mild and agreeable disposition. When he wasn’t out in the hills, he swept up, stocked shelves, made deliveries and did other odd jobs around the general store to earn his keep.

One night, Grisby happened to overhear an interesting conversation. A man was trying to convince the store owner to advance him provisions on a speculative basis, based on a map the man had. This conversation caught Orson Grisby’s attention. He heard the man describe a large cache of gold hidden out in Nevada. He gathered that it was in the notorious 40-Mile Desert, northeast of Reno. Grisby knew this area was way out in no man’s land, a bleak country that only a certain type of argonaut would dare venture into.

In the Sierra, one heard a lot of tales like this of hidden gold, most of which were thin fabrications or confidence schemes designed to fool newly arrived rubes from the east. The easy gold and lucky strikes was gone within a few years. By 1870, larger concerns had moved in and locked up the good claims, employing crews of men and Chinese slaves. Long Tom sluices had been replaced by industrial scale operations that utilized hydraulics, black powder and hard rock tunneling. Most of the small independent fortune hunters that remained found themselves worse off than when they had arrived. Rumors of fantastic riches fed desperate cycles of boom and bust. But Grisby heard something in this particular tale that was different, more believable and detailed. Maybe Orson Grisby was ready to believe anything.

The proprietor of the general store declined the Map Man’s offer. Afterward, Grisby approached the Map Man with his own proposition. The seemingly broke old prospector had actually saved a little grubstake over the years, and he offered to fund a venture with it, the last of his worldly possessions. The Map Man introduced himself as Hiram Butler, a tall spindly fellow with an oddly formal, vaguely military bearing. He wore a long oil cloth duster, high boots, and a black homburg hat. His close-cropped beard and deep-set eyes were striking. One could not help noticing the Arkansas Toothpick, a long menacing knife, that hung from his belt. His movements were stiff and economical, and he walked with a slight limp.

In the store room lit by lantern, beside Grisby’s meager cot, Butler pulled out the map, carefully unfolded the worn brown parchment and told it’s story. He described how a year previous, he and three other men in his mining party had hit a shallow vein way up a gully in the rocky hills rising off the Nevada desert. The spot was beyond Job Peak, not far from the old Immigrant Trail. The miners were running low on provisions and needed to get wood to repair a broken wagon wheel, so they hid a large cache of gold and started back to Reno. The party ran into an ambush of six men, and were caught completely off guard. Butler’s three partners were cut down by the bandits. Butler was shot in the leg and managed to stay alive by playing dead while the others were executed in cold blood on the trail beside him. The bandits cleaned them out, but missed the map they had made, hidden in the boot of the party’s leader.

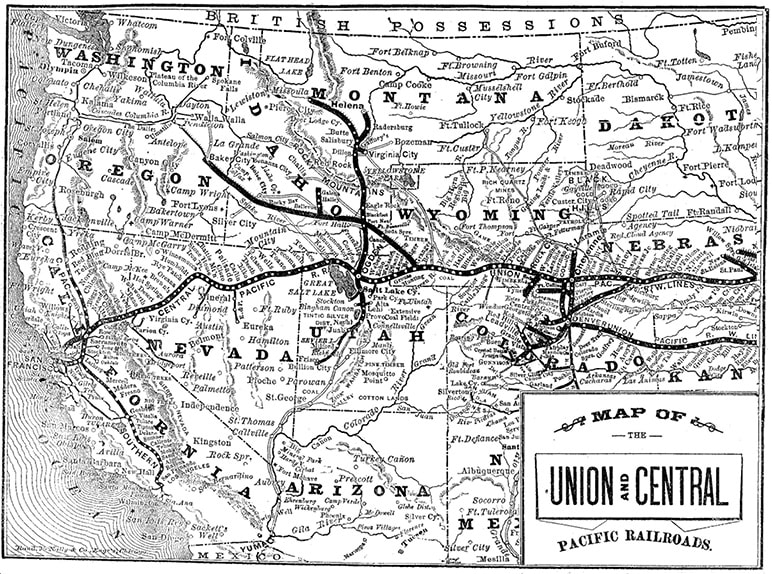

Orson Grisby and Butler, the Map Man, made a deal in Placerville that night. In the following days, Grisby bought two mules, a small open wagon, dry goods and other supplies. In late May of 1870 this unlikely pair of desperado figures set out eastward toward Nevada on an ill-advised treasure hunt.

Grisby and Butler were throwbacks to an earlier time. They were untamed men who hadn’t embraced the creature comforts that were rapidly arriving on the frontier. The two slept outside every night, and knew how to make due with the slimmest of accommodation. They cooked their victuals in iron skillets over a campfire—sourdough biscuits, bacon, beans, and a tin pot of coffee hung above the fire. Their interaction was matter-of-fact and sparse, except when the object of their quest came up. Then, the stoic conversation took on an uncharacteristic animation and liveliness.

These two ragged travellers made their way over the Sierra by way of the newly completed Johnson’s Cutoff, through little mountain outposts named Kyburz and Strawberry. The narrow trails had been hacked out of rock and earth with little more than pick and shovel—along gulches, into mountainsides, across rickety bridges, and through echoing chasms. The snows in the high country had melted and the trail now saw all manner of conveyance. Westbound stage coaches passed regularly, bringing newly arrived pilgrims to the promised land of California. Immigrants continued to come west, for any number of reasons—chasing dreams and mirages, fleeing the law, religious seekers, wanderers. However divergent their various missions, they all shared one desire—and that was to see the mythical ‘elephant.’ This was an idiom of the Gold Rush era meaning the object of one’s quest, the thing you were seeking. One might not have gotten rich, so the saying went, but at least he got a good glimpse of the elephant. Some kind of tableau of natural human curiosity. But curiosity cuts both ways, and the saying later came to represent a negative experience, things gone wrong, calamity.

The mules pulled Grisby’s little wagon slowly down the steep eastern side of the Sierra and skirted Lake Tahoe. Eastward they continued through the lush meadows of the Hope Valley and up the Mormon-built wagon trail some 8,500 feet high and over the Carson Pass. The men mostly chose to forgo the bumpy ride, preferring to walk beside the wagon. The west was full of people reinventing themselves or running from their pasts, so questions about a man’s background didn’t often get asked. This was especially the case with the mysterious Hiram Butler. He spoke little and divulged few details. But in the long hours of their journey Grisby did manage to ascertain that Butler had come west after deserting the Civil War battle of Shiloh. This was one of the horrific battles of that bloody war. With characteristic aloofness, Butler reported having seen unspeakable things on that battlefield, and even worse in the hospital tents behind the Union lines.

The mules pulled Grisby’s little wagon slowly down the steep eastern side of the Sierra and skirted Lake Tahoe. Eastward they continued through the lush meadows of the Hope Valley and up the Mormon-built wagon trail some 8,500 feet high and over the Carson Pass. The men mostly chose to forgo the bumpy ride, preferring to walk beside the wagon. The west was full of people reinventing themselves or running from their pasts, so questions about a man’s background didn’t often get asked. This was especially the case with the mysterious Hiram Butler. He spoke little and divulged few details. But in the long hours of their journey Grisby did manage to ascertain that Butler had come west after deserting the Civil War battle of Shiloh. This was one of the horrific battles of that bloody war. With characteristic aloofness, Butler reported having seen unspeakable things on that battlefield, and even worse in the hospital tents behind the Union lines.

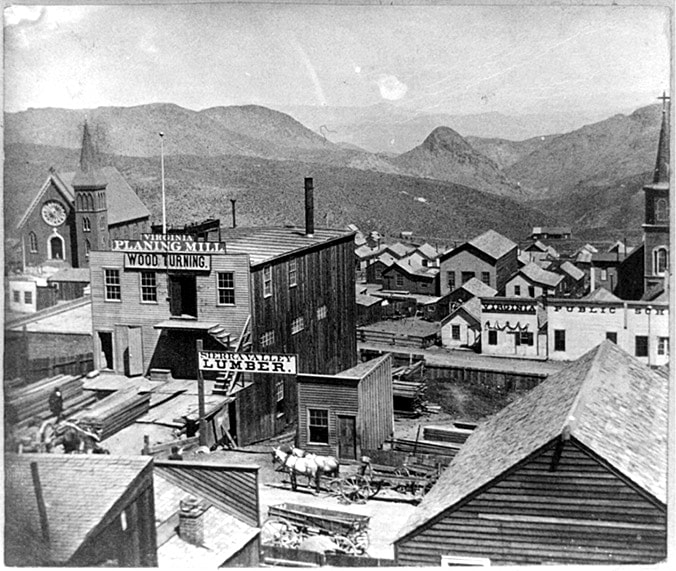

The trail took the two over the Spooner Summit and into Nevada. They passed through Carson City where the state capitol building was being constructed. The mules Grisby had purchased weren’t the youngest nor the strongest, but they were what he could afford. Butler wanted to make a short side trip into Virginia City to rest the animals and to look for an acquaintance whom he said may be able to help them. Grisby didn’t like the vague sound of this—his instinct was to continue along the Carson Trail toward their destination. But the prospect of a rest was appealing to him, and the Virginia City of that day was quite a sight to behold.

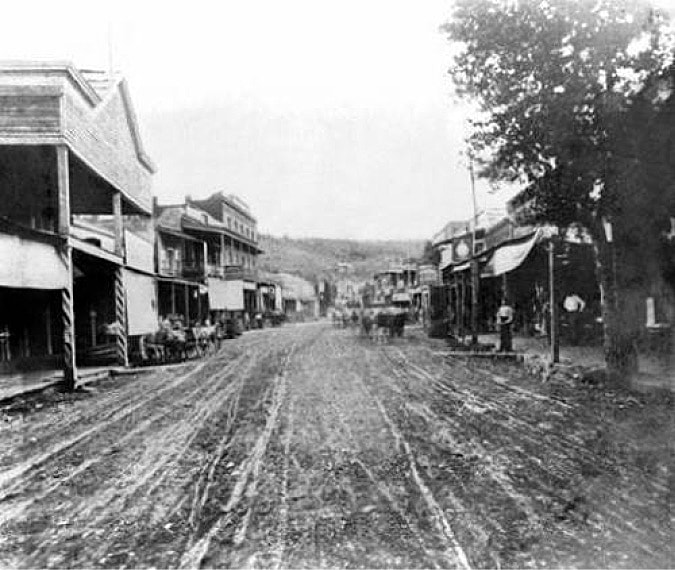

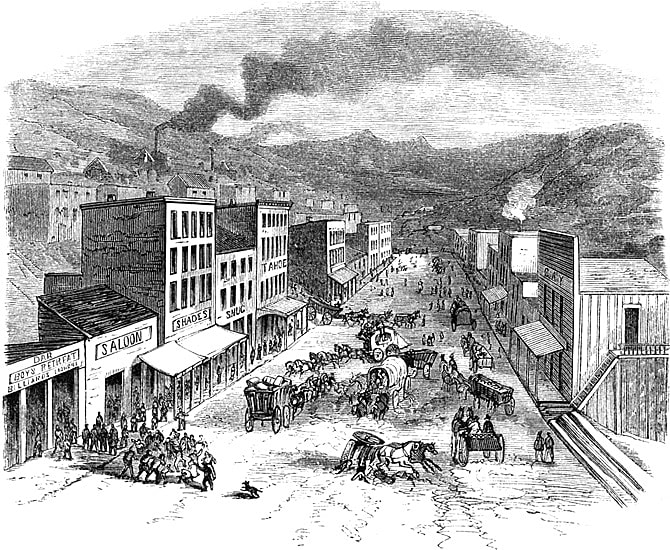

As my grandfather continued his story, I sat transfixed in his little room in the nursing home, my thoughts filled with vivid scenes of western lore. He told me how they approached Virginia City up a long grade, through Silver City and Devil’s Gate, passing shanties and sawmills and people everywhere mining the hillsides. Silver had been discovered in Virginia City ten years before and it instantly boomed into an oasis of temporary grandeur in the harsh landscape, a town centered around the famous Comstock Lode mine. For a time it was said to be the richest town in America. Far removed from the supply chain of California, everything cost more. But people paid with easy money. Fortunes were made and conspicuously spent. It was the boomtown that all subsequent ones were modeled on—the first Vegas of the west.

As my grandfather continued his story, I sat transfixed in his little room in the nursing home, my thoughts filled with vivid scenes of western lore. He told me how they approached Virginia City up a long grade, through Silver City and Devil’s Gate, passing shanties and sawmills and people everywhere mining the hillsides. Silver had been discovered in Virginia City ten years before and it instantly boomed into an oasis of temporary grandeur in the harsh landscape, a town centered around the famous Comstock Lode mine. For a time it was said to be the richest town in America. Far removed from the supply chain of California, everything cost more. But people paid with easy money. Fortunes were made and conspicuously spent. It was the boomtown that all subsequent ones were modeled on—the first Vegas of the west.

On their way in, Grisby and Butler passed ornamented two and three story mansions whose drawing rooms and parlors were surely filled with all manner of Victorian and Nabob fineries, their dining tables laden with champagne and oysters; Grisby stared in awe at the elaborate Opera House.

It was evening. They tied up and secured the wagon and mules in a stable at nominal cost. They walked down C Street past gaudy bars full of hurdy-gurdy girls singing songs. Lanterns lit up the town from every window and along the wood plank sidewalks, where throngs of bearded, dust-covered men drifted in and out of minstrel shows and all sorts of opulent performances. There was even a Shakespearian troupe fronted by a lavishly appointed impresario. They passed organ grinders, opium dens and various commotions.

Butler excused himself and Grisby watched as he disappeared into one of the Fandango houses. Grisby retreated to the stable where they had arranged to sleep. He was glad to spread out his bedroll in the hay, a little overwhelmed by the great abundance of Virginia City. In the morning, he walked the spectacle of C Street again, past fruit vendors, the Miners Union Hall, and stage coaches loading up. Grisby stepped up to a small group of people surrounding a game of Three Card Monte being played on an overturned crate.

The animated dealer called out ‘Chase the lady! Chase the lady!’ over and over as he engaged a man in the front. Grisby recognized the scheme and tapped the unwitting mark in warning. Two of the shills who had been playing a fake game with the dealer pushed Grisby out of the circle and knocked him down. They advanced on the fallen old man. Just then, Hiram Butler emerged out of nowhere and stepped between Grisby and the men, his right hand pulling open his long coat to reveal the revolver than hung at his side. The men grumbled a few foul-mouthed utterances and backed off. Grisby and Butler disappeared quickly into the crowded street. They bought kerosene and headed down Six Mile Canyon back to the Immigrant Trail and eastward. Nothing was said of Butler’s supposed acquaintance that had never materialized.

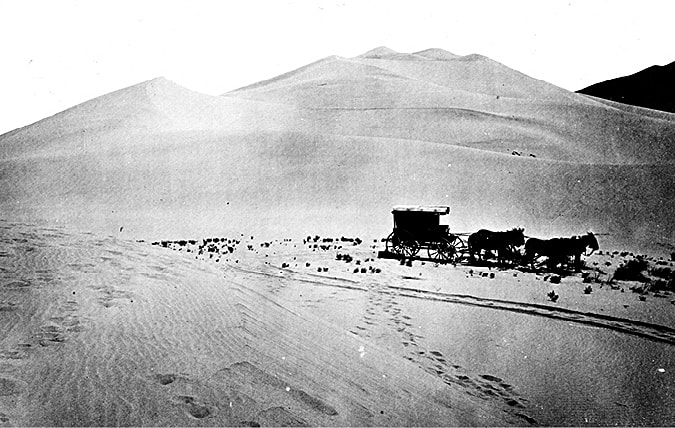

Four days out of Virginia City they crested a rise in the land and glimpsed their destination in the great wide distance—the alkali salt flats of the 40-Mile Desert, lined by hills and low peaks on the hazy purple horizon. This desolate landform is bordered on the north by the terminus of the Humbolt River, referred to as the Humbolt Sink because at that place the river just disappears into the subterranean desert floor. This is a strange phenomenon that remains unexplained to this day. South of the Sink lay 40 miles of wasteland.

In 1844, a Paiute Indian chief named Truckee lead a wagon party from the Sink south across the desert to the rivers beyond. Since then it has remained the most treacherous part of the overland route to California. The wreckage of hundreds of prairie schooners littered the landscape. In the heyday of the early wagon trains, travellers would regularly encounter carcasses of oxen decomposing, bones bleaching in the sun, housewares, sundries and gear strewn across the land, abandoned by people in a desperate struggle to survive. These remnants were witness to who knows what trouble and what hopes and disappointments. Those who ran out of water became trapped in the vast inferno. It was common to see wagons with notches sawed out of their tailboards to make crude grave markers. There were harrowing stories in the immigrant diaries: a husband and wife left with only the clothes on their backs, carrying their swaddled baby, just walking through the dust and heat into certain oblivion; others who went insane from lack of water and had to be trussed up with rope until the crossing was made. There were disputes at gunpoint over water rations between members of the same party. There were wagons that set out into the desert and were never heard from again.

At this point in the story, my grandfather paused for effect and fixed me with a good long look—to make sure I was comprehending the gravity of these details. I clamored for him to continue. He told how they came upon the southern edge of the desert where there lay a bereft little outpost on the Carson River called Ragtown. And he explained how when desperately thirsty wagon trains approached through the desert, oxen would scent river water in the distance. They would go wild and have to be unhitched. Imagine the sight of animals and people, mad with thirst, all stampeding across the last mile of desert to the water’s edge. Those dusty travellers who were lucky enough to make it across would wash their clothes in the river and fill any and all Cottonwood trees and bushes with hanging laundry. All that ragged clothing flapping in the hot breeze must have been an eerie sight, hence the name.

That evening, these two worn characters made camp near Ragtown, their lonesome campfire a small glowing dot in the gigantic black night.

Daylight revealed to their eyes the forboding sight of flat land spread out before them. They started north. Not far in, their wagon wheels sunk in the fine white ashy sand and they became covered in it like ghosts. As they went along, Grisby and Butler felt the full force of the Nevada heat and spied ruins of failed crossings. Due to the deep alkali sand, their progress was slower than they had expected. As they crawled along, the landforms they noted correlated well to Butler’s hand-inked map. They unfolded it periodically to confirm their bearings. On the third night they fell asleep under a desert sky blazing with stars. Visions of gold danced through their dreams. As they set out the next day, Grisby ignored the voice in his head that was telling him to turn back out of the desert heat. All his time in California he had survived hard spots and scrapes by being prudent, but now he could think of nothing but getting to the gold. The mules moved more slowly in the intense heat of summer. The two men became acutely aware of the need to drink less water, to preserve their dwindling supply.

In the distance they saw a large butte outcropping along the hills that rose off the desert floor. They turned and made for it. They were getting close now, but the climb proved to be longer than they had figured. The wagon wheels kept getting stuck in ruts, had to be pried out at a great expenditure of effort and by savagely whipping the tired mules. Finally, around a bend they spotted a wagon with a broken wheel, just as Butler’s story had claimed. Further ahead, a rusted tin coffee can sat wedged between two large rocks—just as the map had shown. It marked a small cave-like opening some twenty paces beyond. When they peered in they saw a large wooden box, half buried. Grisby and the Map Man dug it out. The box was packed with large gold nuggets and scree, more gold than Grisby had ever seen at one time, an unbelievable find! Although they had been pushed to their physical limit by the climb, they rejoiced at their good fortune, managing a few whoops and hollers into the empty wilderness.

They spent the afternoon huddled in a slim bit of shadow as the merciless July sun blazed across a cloudless blue sky. They drank greedily from their canteens in celebration. The two seemed momentarily to have forgotten the perils of their circumstances. Each man’s thoughts were consumed in the calculations and fancies of newfound wealth. That night, they tied the heavy box of gold to the wagon and set out back down toward the desert floor by lantern. Travel by night was cooler but much slower over the difficult terrain. They reached flat ground well into the morning and started back south. The large cistern mounted to the back of the wagon was empty and canteens were nearly dry, but Grisby and Butler were propelled onward by the promise of making it back to the Carson River, at least twenty five miles away. As they struggled to retrace their path, they got turned around several times. Under the midday sun Butler lagged behind the wagon. He rested often, and the two men spoke less and less. Long silences were filled only with the monotonous sound of wagon wheels grinding over rock and sand. The line of the horizon played tricks on their eyes. And desperate thoughts began to fill the silences.

They were partners, but in their situation, the mood became one of unspoken adversary, each asking himself who wanted the gold more—they seemed more like two souls independently struggling to survive. Any loyalty Grisby may have had to the man who saved him from a beating back in Virginia City had vanished. An unsound thought crept into Grisby’s mind concerning how Butler was slowing them down, and how much quicker he might go without Butler, who was breathing with some difficulty now and sweating profusely. This notion turned out to be moot. Later in the day, as they stopped to rest, Butler, the Map Man, leaned over in a heap on the desert floor and never got up. Orson Grisby watched his partner go down, with hardly a reaction. He seemed to sense the finality in the way Butler had fallen. He had no strength to dig a proper Christian grave. He was a long way from the boy he had been in church back in St. Louis. He rifled through Butler’s pockets and grabbed the map—some sort of grim souvenir of this evolving disaster. He abandoned his partner where he had fallen and pressed on now, out of water, miles from any town. A rich man.

That evening, these two worn characters made camp near Ragtown, their lonesome campfire a small glowing dot in the gigantic black night.

Daylight revealed to their eyes the forboding sight of flat land spread out before them. They started north. Not far in, their wagon wheels sunk in the fine white ashy sand and they became covered in it like ghosts. As they went along, Grisby and Butler felt the full force of the Nevada heat and spied ruins of failed crossings. Due to the deep alkali sand, their progress was slower than they had expected. As they crawled along, the landforms they noted correlated well to Butler’s hand-inked map. They unfolded it periodically to confirm their bearings. On the third night they fell asleep under a desert sky blazing with stars. Visions of gold danced through their dreams. As they set out the next day, Grisby ignored the voice in his head that was telling him to turn back out of the desert heat. All his time in California he had survived hard spots and scrapes by being prudent, but now he could think of nothing but getting to the gold. The mules moved more slowly in the intense heat of summer. The two men became acutely aware of the need to drink less water, to preserve their dwindling supply.

In the distance they saw a large butte outcropping along the hills that rose off the desert floor. They turned and made for it. They were getting close now, but the climb proved to be longer than they had figured. The wagon wheels kept getting stuck in ruts, had to be pried out at a great expenditure of effort and by savagely whipping the tired mules. Finally, around a bend they spotted a wagon with a broken wheel, just as Butler’s story had claimed. Further ahead, a rusted tin coffee can sat wedged between two large rocks—just as the map had shown. It marked a small cave-like opening some twenty paces beyond. When they peered in they saw a large wooden box, half buried. Grisby and the Map Man dug it out. The box was packed with large gold nuggets and scree, more gold than Grisby had ever seen at one time, an unbelievable find! Although they had been pushed to their physical limit by the climb, they rejoiced at their good fortune, managing a few whoops and hollers into the empty wilderness.

They spent the afternoon huddled in a slim bit of shadow as the merciless July sun blazed across a cloudless blue sky. They drank greedily from their canteens in celebration. The two seemed momentarily to have forgotten the perils of their circumstances. Each man’s thoughts were consumed in the calculations and fancies of newfound wealth. That night, they tied the heavy box of gold to the wagon and set out back down toward the desert floor by lantern. Travel by night was cooler but much slower over the difficult terrain. They reached flat ground well into the morning and started back south. The large cistern mounted to the back of the wagon was empty and canteens were nearly dry, but Grisby and Butler were propelled onward by the promise of making it back to the Carson River, at least twenty five miles away. As they struggled to retrace their path, they got turned around several times. Under the midday sun Butler lagged behind the wagon. He rested often, and the two men spoke less and less. Long silences were filled only with the monotonous sound of wagon wheels grinding over rock and sand. The line of the horizon played tricks on their eyes. And desperate thoughts began to fill the silences.

They were partners, but in their situation, the mood became one of unspoken adversary, each asking himself who wanted the gold more—they seemed more like two souls independently struggling to survive. Any loyalty Grisby may have had to the man who saved him from a beating back in Virginia City had vanished. An unsound thought crept into Grisby’s mind concerning how Butler was slowing them down, and how much quicker he might go without Butler, who was breathing with some difficulty now and sweating profusely. This notion turned out to be moot. Later in the day, as they stopped to rest, Butler, the Map Man, leaned over in a heap on the desert floor and never got up. Orson Grisby watched his partner go down, with hardly a reaction. He seemed to sense the finality in the way Butler had fallen. He had no strength to dig a proper Christian grave. He was a long way from the boy he had been in church back in St. Louis. He rifled through Butler’s pockets and grabbed the map—some sort of grim souvenir of this evolving disaster. He abandoned his partner where he had fallen and pressed on now, out of water, miles from any town. A rich man.

Moving at an excruciatingly slow pace, he lasted most of another day. One of the jackasses had given out and lay down to die. Shortly after, the other one stumbled badly and fell, breaking it’s front leg. It snorted and writhed on the ground, tangled grotesquely in its harness. Grisby found the strength to pull out his Colt revolver and shoot the beast twice in the head. He had no choice but to leave the wagon, the remaining supplies . . . and the box of gold. He made no attempt to hide it. He staggered on, dazed and doomed now, allowing himself one final look back at the wreckage of their enterprise. What was he thinking to himself, stumbling forward, expending the last bit of his life force? How exactly might the realization of his fate have descended upon him? Had he begun to comprehend his own miscalculations?

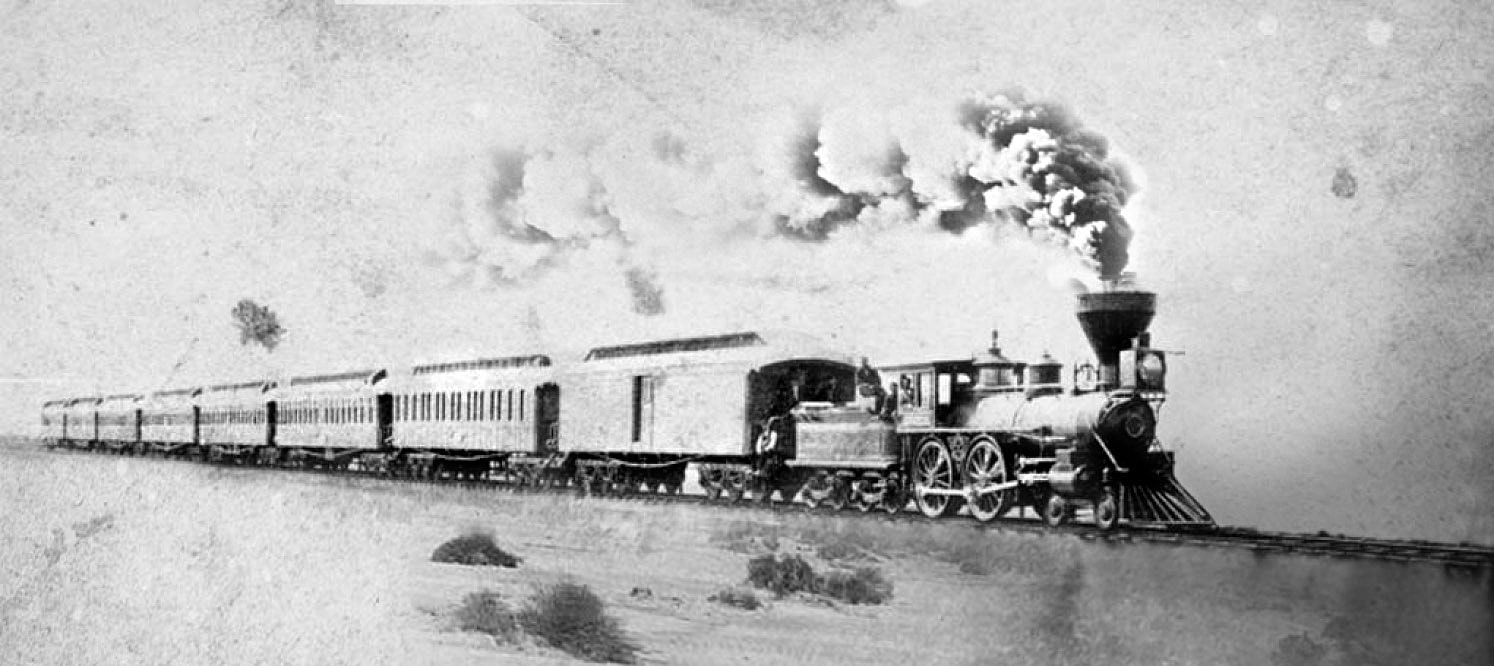

The oppressive heat of the desert does strange things to a man. Grisby’s consciousness was a confused blur. It seemed to him like this was all a dream. He wondered whether any of it had actually happened. Just then, he saw what he thought were railroad tracks ahead in the sand. Something man made and linear interrupting the continuous brown of sage brush and tumbleweed. He fixed his faltering gaze. They were in fact railroad tracks! He had gotten his reckoning crossed up and had veered badly off course. But Providence seemed to be giving one last bit of luck to this unlucky man. He waited for hours beside the tracks. There was no shade. The delusions and pain began to recede, and finally he lost consciousness.

From the westbound train they spotted his lifeless body, and the train screeched to a stop a hundred yards down the tracks. Several people scrambled to the body. A porter shouted, ‘he’s alive!’ They carried Orson Grisby to the train. His deeply sunburned, grizzled face was a horrific sight for those passengers who managed to catch a glimpse of this lost soul being carried aboard. The contrast between the rail travellers, city folk from the east, and this man plucked from the wilderness was stark. A request for a doctor was passed along through the railcars. A young physician who was travelling from Ohio with his family came forward to attend to Grisby, who was now semi-conscious, splayed out on a low bench in the baggage car. The doctor got him to drink a little water and pressed a wet towel to his face. The doctor’s ten-year-old son lingered at the door of the railcar, captivated by the sight of the struggling old prospector.

The train resumed its westward journey on the newly completed transcontinental overland route. It was bound for Wadsworth, Reno, the winding Truckee River Ravine, over the mountains and down into Sacramento. Concluding that his patient had stabilized, the doctor returned to his seat. Orson Grisby rested peacefully now. The Central Pacific No. 60, with the word ‘Jupiter’ painted on its side, ploughed through open desert country.

After a time, the doctor’s son returned and peeked through the baggage car door. Seeing nobody else there, he cautiously walked up to the bench where Grisby lay. The boy watched him for a long time, and then got up the courage to speak, asking meekly, ‘mister?’ The old man turned his head slowly and regarded the boy. The boy was afraid of the freakish old man, but a boy’s curiosity is a powerful thing. He asked what Grisby had been doing out in the desert. Grisby answered in a whisper the boy could hear only by leaning in close. For the next hour Grisby struggled to tell this ten-year-old son of the doctor on the train his whole ill-fated story—the opportunity that presented itself in Placerville, the finding of the gold, the death of Butler and then the losing of the gold. At that point in his story, Grisby grabbed the boy’s arm and in an agitated, incomprehensible way seemed to be trying to give the boy directions to the spot where he had left the gold. The boy would be spooked by this whispered story for the rest of his life.

When the old man finished, the boy watched him gasp for a last breath and fall still, eyes frozen open in a look of mortal terror. The boy noticed Grisby’s arm hanging off the bench and at the end of it, his hand was clenched tightly. He opened the dead man’s coarse, leathery hand finger by finger, and there inside it he saw a sparkling ten-ounce nugget of gold. The old man had clutched it all through his final agonies. The boy took the nugget and slipped it into his pocket. He dared not tell his father about the gold or the story he had heard.

Grisby had been done in, like so many others, by the irrational lust after earthen treasure. At some point, under that powerful spell, he had stopped thinking straight, he had gone simple. A popular expression of the day for gold seeking was to be ‘looking for the color.’ For what else would men put themselves at such peril, disobey the strongest of the instincts, that of self preservation? The west was full of clever, driven men. To this day, people still struggle with the same question: where does ambition end and hubris begin? Even a good man following a true map can be lead astray, tempted beyond the boundaries of his own meager faculty. If nothing else, Orson Grisby had indeed managed to get a good glimpse of the mythical elephant.

The boy on the train who heard Grisby’s story ended up being ill-suited for life in the west. His quiet, orderly temperament was at odds with the wild, seat-of-the-pants frontier. He moved back to Ohio where he married, had a family, and worked as a clerk in the municipal courts. He lived to be a hundred. He outlived everybody else he knew. In a nursing home in Dayton, Ohio the boy on the train, now an old man, told this tale to me, his grandson. Stories retold, passed down from blood to blood, a chain of odd and capricious events—history itself.

I remember the day my grandfather told me this story, to which I have taken the liberty of adding certain conjured details. After he finished, he lumbered up from his chair in the nursing home and went to a chest of drawers, where he pulled out a white handkerchief. He unfolded it to reveal to me the talisman he had kept all these years—that same ten-ounce nugget of gold he had taken from the lifeless hand of Orson Grisby.

|

© Copyright Confluence Studio. All rights reserved.

|