Action Heroes on Mount Parnassus

|

Justin Panson

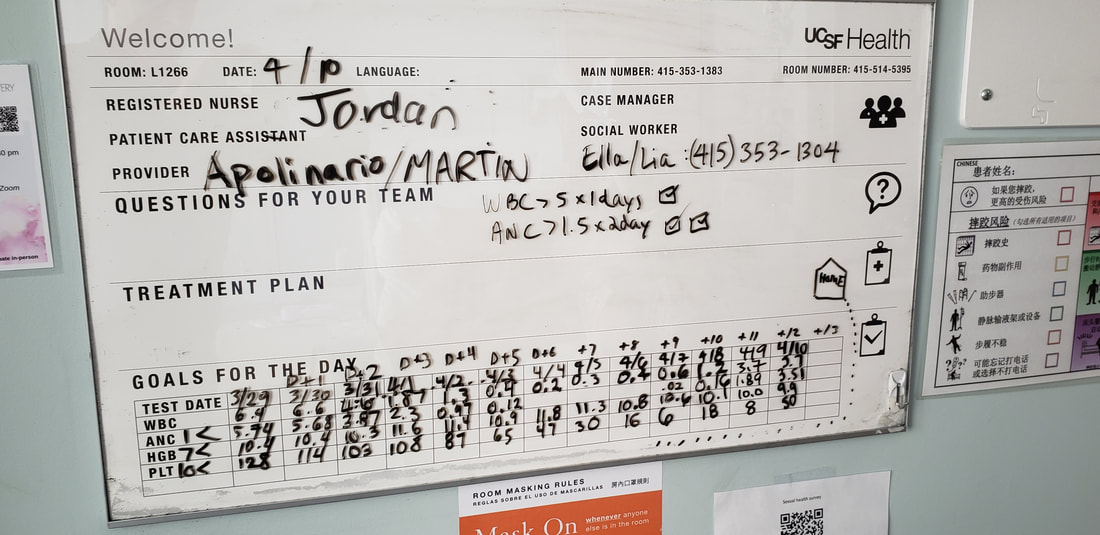

I finally met Dr. Wolf today. Late in the afternoon he walked into Megan’s hospital room. As she and I have been camping out in these close quarters for several days, the room was crowded with snacks, laptops, power cords, clothes and personal effects scattered amid the IV rig and other medical devices. He stopped in on this day because a few hours earlier Meg had received the last of her 12 bags of stem cells, an exhausting two-day process. Dr. Wolf looked like an unassuming guy off the street, wearing a woolen flat cap and an REI style raincoat. He had this sweet grandfatherly manner as he checked in on Megan, calling her "kid," chit chatting a bit, and then mentioning the bad days to come as her system is wiped out and then begins to reboot itself. As he was about to leave I thanked him for his care and mentioned how impressive the stem cell transplant procedure is. This kindly white haired dude replied that he didn't invent it but just brought it here and set up the program. He said, “In 1978 I went to a lecture here by a visiting clinical researcher named Don Thomas, and it blew me away.” He immediately recognized how revolutionary Thomas’ work was and got permission to go up to Seattle to study under him at the University of Washington.

I had to look up this Thomas guy. In work that began in the 1950s, Dr. E. Donnall Thomas pioneered bone-marrow transplantation and blood stem-cell transplantation, lifesaving procedures for people with leukemia and other cancers of the blood. They work by destroying a patient’s diseased bone marrow with near-lethal doses of radiation and/or chemotherapy, then transplanting healthy marrow. When the transplanted stem cells graft onto the bone marrow and begin to grow healthy new white blood cells it is nothing short of a miraculous process—new life! Thomas worked stubbornly for years against the widespread belief that bone-marrow transplants would never work. It took almost two decades after his seminal paper was published in 1957 for the procedure to become accepted therapy. Through the 1960s and into the 1970s there were many mainstream physicians who said this would never work. Some suggested Thomas’ experiments should not continue. Dr. Wolf told me “people thought we were crazy.” Thomas has been described as “brilliant, modest, quiet, and able to surround himself with great scientists, clinicians and nurses because he was generous with praise and would attribute successes to those individuals around him.” This year, about 60,000 transplants will be performed worldwide, including the one millionth transplant in all. The work Don Thomas did to establish marrow transplantation as a successful treatment for leukemia and fatal diseases of the blood is responsible for saving the lives of hundreds of thousands of people around the globe. In 1990, Dr. Thomas was awarded the Nobel Prize for medicine "for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." I'm pretty certain Dr. Wolf was overly humble in describing his own role over the past 45 years. Skimming through his bio on the UCSF website you learn that Jeffrey Wolf has been working on the same set of medical problems since the late 70s—when Meg and I were just children. He has more than 60 published research papers to his credit, the names of which I can neither pronounce nor understand. He established treatment and research programs at Alpha Bates in Berkeley and then later here at UCSF. At a time when guys his age are out on the golf course he is currently running a clinical trial for the next generation of stem cell procedures that involve editing the cells on a genetic level in order to program them to kill cancer cells. He told Meg, “we’re going to take you (our patients) to the future.” It's absolutely head spinning for a lay person to fathom this kind of intricate understanding and control of worlds that are invisible to the eye. Newton famously described the cumulative nature of scientific work, saying that if he saw further it was because he stood on the shoulders of giants. So too you see the genius work of Thomas begetting Wolf and others, and now handing forward to the next breed of genetic researchers. They are all playing a very long game, measured in decades and lifetimes. Just as quickly as he had appeared, Dr. Wolf walked out of the hospital room like some kind of figure from a movie. As he disappeared the reductive thought crossed my mind: this is the guy who is saving Megan's life. The UCSF Cancer Center is housed in a worn, antique mid century tower. It has been an adjustment for us to sync up to the odd continuum of hospital life, where time seems to exist in a suspended fluorescent-lit state, detached from familiar daily patterns. This medical campus spans both sides of Parnassus Avenue, a high point that overlooks Golden Gate Park and all of San Francisco. From Meg’s room on floor 12 we can see a sweeping view of The City, from the sea to the Golden Gate Bridge and out across the bay to Richmond and over to the skyscrapers of the financial district. Taking in such a magnificent vista from the trenches of a nasty fight with cancer is an irony that has gone unspoken during our stay. Parnassus Avenue is a reference back to Mount Parnassus, an 8,000-foot high mountain range in central Greece, a few hours northeast of Athens. This majestic looking mountain is the locus of so many Greek mythologies, involving the likes of Apollo, Orpheus, Dionysis, the Oracle of Delphi and of course various nymphs. Out of these colorful histories Parnassas has come to symbolize a holy place where the power of divinity is manifested, where the Muses dwell, the home of poetry, music, and learning. All of this heady stuff seems more and more appropriate the more I learn about Dr. Wolf’s work, and the deeper Meg progresses into her two-week stay, which is the culmination of months of preliminary chemo treatments, and an endless sequence of pills, blood work, charts and exams. When you are young, healthy and invincible you do not give much thought to the medical world. But today I have a new sense of gratitude for the healers and medicine men and women up here on Mount Parnassus. Especially at a time when doctors and researchers have been personally attacked by extremists who know nothing of the intricate and difficult problem solving that goes into something like a vaccine or a treatment for blood cancer. There’s this pop song that keeps spinning through my head this week, by a band called the Flaming Lips. It’s called Waiting for Superman, a haunting ballad of uncertain hope in difficult times: Tell everybody Waitin' for Superman That they should try to hold on nest they can, He hasn't dropped them Forgotten or anything It's just too heavy for Superman to lift We as a culture are fascinated with stories of action heroes--the muscular character out of comic book lore in some outrageous costume, cutting across the sky at the last moment, death-defying, gravity-bending, explosions all around...and he or she saves humanity. I have come to understand the real action heroes are the researchers, doctors, nurses and teachers who do the really important work—without an audience, in relative obscurity—the life and death work of everyday. When I later shared this idea with him, Dr. Wolf was quick to share the credit, saying, “The real day to day heroes though are the nurses on our unit. Watch them carefully. They could do much easier jobs but choose to work on this most taxing unit.” The day Meg learned she had cancer she came home from her appointment and I was sitting in the backyard. She hadn’t wanted me to go with her. She wanted to go by herself. She was crying and we hugged for a long time in the warm sunshine. In that moment we both knew our lives had instantly taken a radically different trajectory. She is the most amazing and big-hearted mom of our three kids. From as early as I can remember she just instinctively knew what they needed and was always there for them. And she is also a high-functioning VP at a global technology company. She has this kind and generous spirit that is hard for me to adequately put into words. Everyone sees the grace and the inner beauty. That is why it makes no sense in this absurd life for her to be the one tapped with this fate. As accomplished as she is, she will always be the baby among her four siblings. Her sisters and brother all live close and have rallied around their sister in small ways that add up to something more—the everyday little acts like going to appointments with her and bringing bread and flowers are revealing of a profound and unspoken closeness in our family. Cancer is often personified as an evil entity that must be vanquished. The battle metaphors help people cope, and make the murky cellular world comprehensible in our culture of simplified adversarial stories. When you dig into the fight metaphor, there are several parts to it. They say a patient’s own positivity and will power can make a difference. In this regard, Meg is strong and has so much support. Beyond personal strength, in times of medical emergency we call upon the fates and the deities of our own choosing to deploy their supernatural forces. We would be lying if we said we didn’t look upward in these difficult moments. And then finally, and most thankfully, Meg’s life is now in the hands of the healers and the real action heroes up here on Mount Parnassus. March 29, 2023 |

|

© Copyright Confluence Studio. All rights reserved.

|