CALAMITY TOURIST, ACT II

Lost & Found in the Black Rock

Epic Camping Misadventures, Biblical Reckonings, and the “Immenseness of Everything”

|

Justin Panson

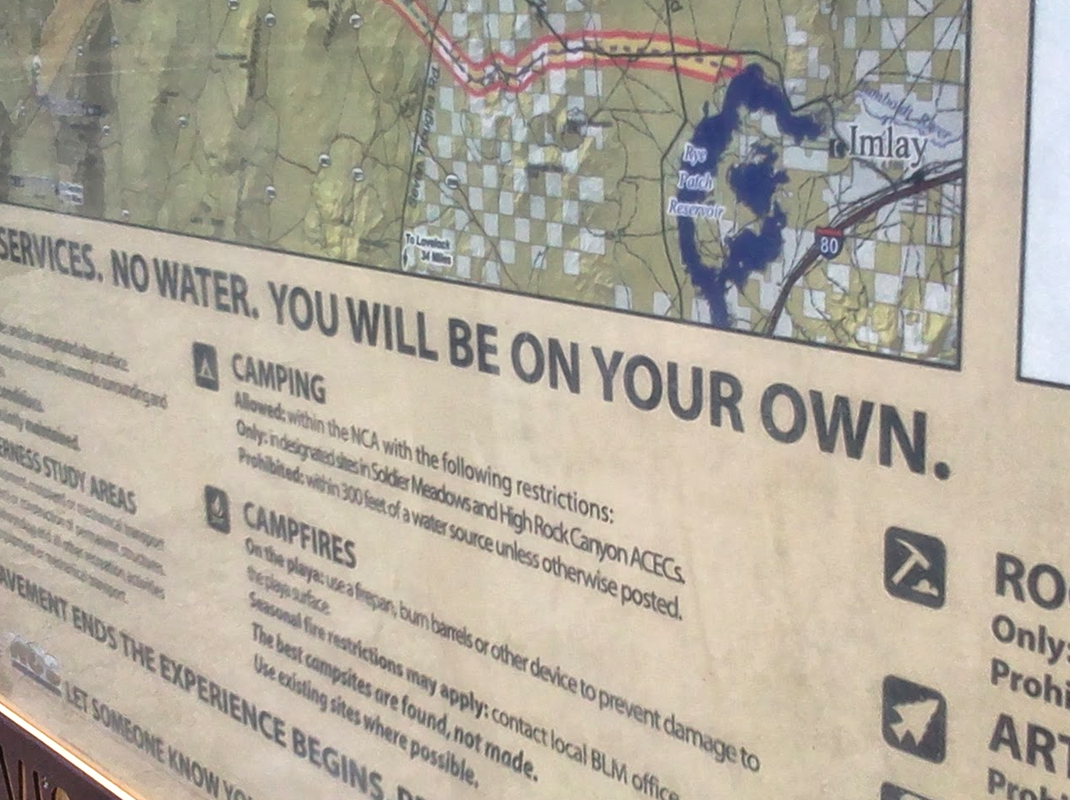

Escaping the Grid We rolled out of Sactown in Bob’s Toyota Tacoma, hauling a janky load stacked up past the contractor rack. There were big arcs of white PVC piping and wooden poles lashed to the rig. With this homespun get-up, we looked like the second coming of Jed Clampett and his kin folk. We humped it over the Sierra Nevada, the overloaded, late model engine struggling on the uphills. Past Gold Rush outposts of Cisco and Secret Town, over the Donner Pass and into Nevada, bound for the Black Rock Desert. This is a stark barren land form north of I-80, in the heart of the Great Basin. It is notorious for having swallowed up immigrant wagon trains in its inferno, and more recently famous as site of the Burning Man art festival. We were going out there to see the desert without all those 90,000 frolicking art freaks. The event we were bound for was billed as a small gathering of core Burning Man people held on the 4th of July every year—The Fourth of Juplaya (playa is the Burner name for the desert floor). There would be maybe a thousand people informally scattered in clusters across the wide landscape. Bob and I had gone out to Burning Man about five years back. I was the novice, his wing man for six days of crazy desert living. Everyone has their own conception of what Burning Man is. The beautiful thing is that nobody is wrong—it is many things to many people. One thing is sure: it’s a lot more interesting and nuanced than the druggie/hippie shorthand used by the mainstream media. It is a countercultural playground spectacle that defies easy explanation—artists, performers, tech geeks, enlightenment seekers, partiers, ravers...a whole shabby, multicolored sea of humanity floating through wondrous scenery in outrageous costumes—fur, sequins, Victorian top hats, disco platform shoes, a mash up of hundreds of years of disparate fashion...or no clothes at all...all these souls frolicking in the dusty flatness and the glowing LED-lit nights, with fireworks exploding all around. It is not an exaggeration to say the festival explores the limits of the human imagination, and beyond. But this trip would not be that sort of wild, elaborate affair—rather, quiet and meditative--no $300 ticket to get in. No raves filling the air with thumping techno beats. We hoped it would be more about the landscape and camping. Camping and DIY is where my friend Bob comes in. He is the consummate tinkerer, builder, veteran camper, rigger of structures, a longstanding member of Sacramento counter cultural, bohemian circles. As we drove, I posted to Facebook that we were heading out, and our friend Anton posted back that he just heard from some of his friends who were stuck out on the playa. He warned of unseasonably wet conditions and to avoid the whitish sands at all costs. We thanked him and kept on rolling east. We started talking about the conditions we might find and then pivoted to imagining the immigrants who came through the Black Rock Desert in the 1850s on their way to the promised land—the difficulties they had in this terrain, and the likelihood they didn’t know exactly where they were at times. We tried to contemplate the mindset of having to accept that level of uncertainty. And how different that was from our world that is known down to specific GPS coordinates, the elaborate grid work of cities, rivers, all the connections between people. Bob and I were talking about this stuff, riffing on map reading vs. GPS, and wondering if, as a consequence of technology, the ancient skill set of reckoning has eroded, and might soon completely disappear. The designed, developed, urban-planned world, all the way finding efficiencies had, in the space of a few short years, threatened geographical skills. Bob speculated on the intensely local origins of way finding, traced all the way back to early humans who found their way following animal trails. He marveled that animals, on a more instinctual level, know how to go. Deer track leading to trails and then roads and finally to interstates. On and on. Everything is local. The history of the Burning Man festival, its creation story, is a beautiful tale evolved organically from humble origins. One of the largest festivals on the planet started from a single gathering of San Francisco folks, loosely organized around what they called The Cacophony Society—performance artists, pranksters, musicians. Somebody had broken up with a girlfriend and needed to find a path forward. He and his friends built a wooden man figure out of 2x4s out on Baker Beach. They gathered things they wanted to move on from...put them with the wooden figure and burned it. Today the Man structure and the Temple are world class engineering and architectural marvels. Radical self reliance and self expression are the central tenants. And also freedom, unapologetic utopian idealism, and a strong DIY ethic. We turned off interstate at Fernley and headed north, past Pyramid Lake, continuing our discussion of overly weighty matters, killing time, watching the increasingly prehistoric land forms roll by in the windows. Bob and I continued our talk about the whole sequence that lead to our current state of human social dependency: explorers, then settlers, then tourists like us. Were we tourists or pilgrims? We turned back to the story of the west-bound pilgrims lost in the wilderness. Bob, known for his quiet prescient insights, said that today getting lost is when the batteries die. Wise. I flashed on memories of my mom who was always getting lost, owing to her poor sense of direction, and our embarrassment as kids at being in the helpless position of driving aimlessly and pathetically, approaching strangers for directions. Such was the path of our presumptuous chit chat as we motored further out. We got to Gerlock, the town at the southern end of the Black Rock desert, and poked into the general store to ask about conditions. We didn’t get more than a disinterested ‘it should be OK.’ We stopped in at a non-profit dedicated to preserving the Black Rock. We chatted with an earnest guy behind the counter and thumbed through their brochures and literature. Into the Flatness Onward we went, up the road that skirts the western edge of the Black Rock, to the 12-mile entry point. We stopped at the official entrance sign. Bob lowered the tire pressure down to about 18 PSI and I took note of the ominous Nevada State Parks sign: THERE IS NO WATER. YOU WILL BE ON YOU OWN. I took a picture of the sign, and paused to contemplate the finality of the warning, wondering why people voluntarily seek out such an inhospitable place. We followed a well worn set of ruts out into the sand and turned north, out into the otherworldly, wide, flat expanse of alkali dust, struck by it all, the vastness, the sense that we were on the surface of this strange planet earth. We followed the double tire ruts that got deeper and then more shallow, past puddles and dry spots. Bob and I didn’t really have a plan. We thought we would try to get up to the eponymous Black Rock on the northern edge of the desert. We could barely see it, this massive black blob way, way out on the horizon of this landform that is 40 miles top to bottom and 4 miles wide at parts. Bob knew of a few mini-playas up there—flat valley offshoots of the main desert, smaller and surrounded by rock faces on all sides. We thought it would be cool to get up in that stuff and camp out. Bob lowered the tire pressure down to about 18 PSI and I took note of the ominous Nevada State Parks sign: THERE IS NO WATER. YOU WILL BE ON YOU OWN. I took a picture of the sign, and paused to contemplate the finality of the warning, wondering why people voluntarily seek out such an inhospitable place. We blithely followed that road, drinking in the scenic beauty, taken with a sense that this trip, planned and looked forward to for so many months, was upon us and we were actually on the Playa. All of a sudden a big deep puddle was on us, directly in front of us in the windshield. Bob swerved left just in time. "Shit, that was close!" That woke us up. We were then immediately in a sequence of dodging wet and dry where we couldn’t slow down and risk getting stuck. In soft terrain, momentum is your best friend. Just keep the engine gunned and keep your eyes down the road a piece to try to anticipate what’s next. Finally we found a good dry spot and stopped and got out. We took a few pics and drank a beer, aware of the risky terrain but somehow undaunted and hoping to find dryer ground as we headed north. We kept going. In hindsight, we should have done a 180 a this point. Just a little further Bob made a series of correct split second left/right decisions on the fly. And then he made a wrong one and we were immediately caught up in heavy muck. He floored it but we lost speed, fish tailed and ground to a stop, stuck in deep mud. We got out and looked at our predicament and realized just how fucked we were. It’s a heart sinking feeling. The mud was up pretty high on the tires. I pushed and we got it rolling about 10 yards and then stuck worse. at this point I was the excitable one, repeating to Bob how fucked we were. Stranded in Deep Mud Bob, ever the optimist, was trying to say reassuring things but it was understood that we were 20 miles out in the middle of nowhere, desolate. nobody close, no cellular coverage, the prospect of anyone being this far up north very remote. We tried several more times with me pushing and Bob gunning it, but we just got stuck worse. What followed was this period of time where we were walking around, circling the rig, and helplessly trying to think of anything we could do—trying to come to grips with this contrary reality. There was nothing. We were going to be slogging a long way. Brutal. Trip plans finished. A long, nasty hike out in the heat. Dumb fuckin' tourists, in way over our heads. How do you like the scenery now, asshole? We were going to be slogging a long way. Brutal. Trip plans finished. A long, nasty hike out in the heat. Dumb fuckin' tourists, in way over our heads. How do you like the scenery now, asshole? Part of the Burning Man ethic is to survive the often harsh elements—wind, dust, rain, lack of comforts—and do it with some sort of grace and resignation to the larger fates. In other words, manage in less than ideal circumstances without totally losing your shit. You hear all these stories of hardship from veteran Burners. So this was our little test. The dire hand wringing went on for what seems like the better part of an hour. The contingency thinking started to kick in. At what point do we start trying to hike out? Or are we better staying with all of the provisions, water, shelter of the truck? Would it dry out over another hot day, or was there more rain on the way? If we waited, we could be out there several days. At some point I was looking south, scanning the horizon desperately, and then I thought I saw something. I looked more closely through distance and wavering heat and light, trying to fix my gaze more precisely. I thought I saw the tiny black dot of a vehicle...was it coming north? Squinting, trying to make out the nearly imperceptible movement. Yes, coming toward us! On our way up we didn’t see a single car. There were likely going to be no other cars that day that far north. We tracked it for a bit and then I took off running for it, frantically yelling back to Bob to put water in a day pack and catch up to me. They were at least a mile off. I’m running, and after I got closer started waving my arms and calling help. How many times in your life are you actually running and yelling in all sincerity ‘help’ and waving your arms wildly over your head? What a pathetic sight it must have been. I saw a frayed up small piece of plywood on the ground and grabbed it, thinking we may need it to get unstuck. I had meant to bring planks to put under the tires in case we got stuck. I had also meant to bring a shovel. So, I was waving the plywood in the air, desperate, running, yelling into the big emptiness, “Help! Help!” Did they see me? Or was I lost in the light brown sea of tumbleweeds and crags. The desert seemed especially large at this point, and I started running through all the ways in which this sort of flat distance can play tricks on one’s vision. They did see me and started walking toward us. Eventually I met a group of five people, clearly burners here for the Juplaya gathering, in crazy, celebratory outfits, men and women of various ages. I caught my breath and awkwardly explained what I now realize was self-evident. They had seen we were stuck. There was a sense of relief. At this point, I foolishly thought we were saved. I’m running, and after I got closer started waving my arms and calling help. How many times in your life are you actually running and yelling in all sincerity ‘help’ and waving your arms wildly over your head? What a pathetic sight it must have been. Rescued by a Merry Band of Hippies We introduced ourselves and after after a bit of awkward conversation I asked tentatively if they would hike back with us and help try to push the truck out. I told them they shouldn’t try to drive any further--which, in hindsight was a statement of the obvious, but it needed to be made. Eventually Bob caught up and joined the circle. Then we set out. Walking with these strangers over this desolate landscape and making small talk was a bit surreal. But everyone just seemed to understand the situation and be comfortable with this mission of mercy, and that made it seem less odd. When we got to the truck and saw again how sunk it was in the deep mud a new sense of hopelessness came over me. The seven of us sort of walked around and assessed from all angles. We decided to unload the truck—less weight would give us a better chance to get it out of there. When we pulled the big cooler out, I dug in and offered everybody cans of beer. This seemed like an unserious move, but there was some sort of hospitality element to it that was important to me in this moment. The coolest thing happened next, as everyone noodled through this problem: push it forward but uphill, or backward? Where’s the closest spot of dryer ground to aim for? The guy with the big tufts of wild hair sticking out from a straw cowboy hat seemed older than the others, and perhaps the de facto leader of this leaderless crew. His soft spoken, thoughtful way inspired confidence. His name was Allen. I went over to him and had a little side discussion. Then Bob and I got down on our hands and knees in the muck and dug out all four wheels the best we could with our hands...while the others watched and drank their beers. I've been out jeeping in the Sierra back country with the sorts of characters who actually likes to get stuck. After a few of those outings, I realized that getting stuck was the whole reason for their mission, to employ all the gear, the winches and tools and old fashioned Yankee ingenuity to get unstuck. This wasn’t at all that sort of thing. Other than these folks we were dumb lucky enough to track down, we had absolutely no way out, no extra margin, no level of contingency to fall back on. With Bob at the wheel, and everyone else pushing from the front, the truck actually started to move! And it gained some momentum, and we managed to move it about 15 yards down the small rise what looked like a dry creek bed—more likely just one of the temporary water flows on the desert floor when it rains. This was a great sign. Then another thoughtful collaborative discussion about whether to do the next 40 yards backwards, or to execute what would be a 10-point turn in this tiny spot of dryer ground. We went back and forth several times, knowing that it would be very easy to get re-stuck or stuck worse. We decided on turning it around, which was a good decision. Then another burst of the engine, with all of us pushing...and we were out to a much better place. After we repacked the truck bed, the coolest thing happened. These folks, our rescuers, walked several hundred yards back toward safety and positioned themselves, one-by-one, at intervals to mark the good path. How did they know how to do this? By some sort of playa intuition, or just common sense. One wrong turn off this marked path would likely get us stuck again. Bob gunned it along this path, fishtailed at a few points and made it to the dry ground at the end of the human chain! A huge relief. Someone got in the cab with Bob and the rest of us climbed on top of the big tarped pile in the back. We rode the mile back to their rig. Sitting up on top of the loaded truck, It had this triumphant feel...just a few short moments separated from deep despair. I chatted with Caitlin who was hanging on the back, noting the lovely juxtaposition of her wide-brimmed, graceful sun hat and welders goggles. We followed them the 20 or so miles back at their compound, a high geodesic dome framework with sub structures under it and a big common area in the middle. Allen offered us a strong bit of hashish they called ‘earwax,' which we smoked, sitting in a circle with several others in addition to our rescuers. It wasn’t till then that Bob and Allen figured out they knew each other. These folks were from good old Sacramento. Allen and Bob’s wife Kim were friends. You Guys May Want to Save What You Can Allen and his friends had been out there a few days already and were settled into a carefree, light sort of flow. People seemed to drift in and out of the scene, pleasant, friendly and curious to meet us and hear our story of being rescued. There were dudes in baggy balloon pants, crazy top hats, bikinis, ensembles of a mad max warrior style, and billowing multicolored peasant dresses. After a time we decided we should set up camp. Still in a bit of shock from nearly having been badly stranded, we figured it was best to locate near these guys and their groovy Burning Man style compound. One of the defining things about Burning Man is the inventiveness, the art, and especially the elaborate art cars—a 20 foot paper mache whale cruising by, pirate ship, school bus made into a big yellow aluminum duck, dragons, robots. On and on and on, beyond words, beyond the limits of the imagination. The structures in particular reveal the cleverness, art and engineering feats, from humble geodesic domes all the way up the Temple itself, architectural marvel, a collaboration among a team of engineers and architects from around the world, center of the ritual burning of things people want to let go of. You see the whole gamut from the profound to the whimsical: a funny, pseudo retro mini golf course, roadside refreshment stands, roller rinks, fun houses of all sorts. All of it mobilized out to no man’s land in a logistical effort that is in itself a work of art. We set up a few hundred yards from Allen and his band of merry people. Being a longtime tinkerer and rigger of camping structures, this was Bob’s heyday. We set up the two quonset huts, made of PVC poles bent into upside down U’s with the ends fitted over iron stakes pounded into the sand, a center spine pole connecting the U’s, and tarps stretched over them and attached. There was one for a kitchen and one for sleeping quarters. We put up a shade tarp, suspended on tall wooden poles, and all of the other infrastructure of camp: chairs, tables, large jugs of water, green Coleman stove, duffles, sleeping bags. We tied things down reasonably well, knowing there was an additional level of tie-down that we would attend to later, after we stopped to have a beer and enjoy the fire show of the sun sinking under the wide flat desert horizon, colored by a moody wash of deep purples and oranges . We walked back over to the big camp and met some of the other people who weren’t part of the rescue mission. The evening festivities were underway. Allen asked about whether our camp was all set up. At that point we walked with him over to the edge of his camp and looked out on our camp in the dusk. Bob had strung Christmas lights along the shade structure, which made a nice visual from where we stood. He gazed out proudly on his huts. I noticed a few gusts of wind rising up, but nothing to cause concern. As if on cue from some cosmic schedule, Allen looked out at our meager camp and spoke these words, "You guys may want to save what you can.” We looked at each other, not quite understanding the dramatic sort of statement. And then not ten seconds later a big gust of wind ripped through, and we saw in the distance the stuff from our camp was blowing out into the desert. We took off sprinting toward camp, grabbing stuff sacks and plastic bags and stray clothing. As if on cue from some cosmic schedule, Allen looked out at our meager camp and spoke these words, "You guys may want to save what you can.” We looked at each other, not quite understanding the dramatic sort of statement. And then not ten seconds later a big gust of wind ripped through, and we saw in the distance the stuff from our camp was blowing out into the desert.

Just as we made it to camp a strong storm was bearing down on us. Increasingly higher winds that were blowing the quonset huts sideways. It seemed at any moment the huts might just completely rip away. We were yelling at each other over the howling wind, trying to coordinate our efforts to save camp. Over the course of the next hour or two we managed to tie the huts in several places to the large army surplus water tanks. The knot work and roping was pathetic. It was hard to execute fine motor skills in the turbulent situation. Rain sheeted down violently. Bob and I stationed ourselves at each of the hut ends, and when the violent gusts hit, we braced the huts. Over the next several hours we braced like this as more intense gusts came, and otherwise hunkered down or continued to tie things down further. At one point during what took on the sense of an ordeal, in the midst of thunder and lightning show, and sheets of rain, we could hair our neighbors out in the ground between our camps dancing and singing at the top of their lungs. I remember just thinking how much less extreme everything seemed in their mode. Finally we set up cots in the one hut that was still mostly together and crashed. Empire of the Sun The next day was the sun-baked, crystal-clear day we had come for. Just a stellar, arid high desert sky. We spent a few hours in the morning repairing our tattered camp, and then we commenced with the day rituals: chaise lounges, bare feet, shades, beer. Bob donned the Charthart utility-kilt. Periodically throughout the day people stopped by our camp, in dune buggies, dirt bikes, and a group on foot, who had walked from their encampment about a mile or two across the playa. Our neighbors came by and inquired about how our night had gone, and we noted the fortification efforts we had taken. Later we visited their camp and marveled the mud soaking pit they had constructed. Several folks were covered in dry mud that affected a tribal look. Toward mid part of the afternoon we noticed a dark sky gathering way, way down to the south. We tracked it’s approach through the balance of the afternoon, knowing it was headed right for us. Toward late afternoon it got windy with that sense of an impending storm. We tied down everything and waited. There was something odd and resigned in waiting for an inevitable blow that is coming, like waiting to get punched in the face. Gale Force Storms & Biblical Damnation When the storm was almost on us we lashed down the chairs we had been sitting on, the last two unsecured things, and then braced inside one of the quonset huts. Over the next ten minutes it got progressively stronger and strong, to the point where it seemed like we and our whole camp might just get blown away. We were bracing with all we had. With the winds gusting at upwards of 70 mph, I began to fear for our safety. I grabbed both of our day packs and made a run for the truck. It was difficult to even open the door to get it. Once in, I yelled across the 10 yards for Bob to abandon the hut and make a run for the truck. He declined, continuing to heroically brace his beloved structure. I seriously thought the truck was the only safe place. Were these the end times? the phantasmagorical prophecy you hear from the lunatic fringe? The haunting, dirge-like stanzas of the traditional folk hymn “The Lone Pilgrim” rolled through my mind: "The tempest may howl and the loud thunder roar, And gathering storms may arise, But calm is my feeling, at rest is my soul, The tears are all wiped from my eyes. The cause of my Master compelled me from home..." After about five minutes this gale force storm eased off. It was followed by three other waves of hard rain and wind spanning several hours. At some point, we said the hell with it—camp was trashed and the storm kept coming. We huddled into a dry spot in the kitchen hut, cracked beers, and resigned ourselves to make the best of it. We were hungry, so in the middle of the pelting rain we fried up a couple of big slabs of salmon in a cast iron skillet, at this point unphased any longer by the storm. Eventually the weather tapered off and we got some sleep. In the morning we woke up to find we were camping in the middle of a massive lake. Even taking just a few steps in the muck resulted in your shoes getting caked with a thick goo to the point where it was so heavy and think you could hardly walk. Not ideal. We decided to cut short the final few days of the trip and bail out. We waited all day for the ground to dry out enough for us to attempt to drive out. We packed up and then in the late afternoon thought it was dry enough to make a run for the asphalt road. We said goodbye to our friends and pulled out, carefully picking our way around the swamps and out to the road. The Immenseness of Everything Candice, one of the people in Allen’s group, summed up the experience perfectly, saying she was out there ‘to let the immenseness of everything wash over her.’ I can still see her, eyes closed, face tilted toward the sunshine in a blissful state. It struck me as a beautiful expression, something right out of Kerouac. In the escalating sensory overload of everyday life, sometimes you need an experience like Black Rock to reset yourself—the epic sky and flatness. Despite our difficulties, it was a worthy endeavor, a transcendent experience. Beyond the geography, it was meeting these people that made it cool, their sense of adventure, their embrace of the experience, their expansive attitude. These guys were pilgrims in the truest sense of the word. More than the kaleidoscope Burning Man infrastructure, it’s the attitude that makes the experience singular: cool people, a gift economy, a great vibe, unapologetically utopian. It’s an experience free of a lot of the more harsh, competitive elements of industrial society. I learned how to act according to the set of manners and ethics of the festival. Don’t judge the more bizarre aspects, don’t leer at the naked ladies, share and be big of spirit. I learned about the philosophical underpinnings of the event: Radical self reliance and self expression. Do it yourself. Freedom! We came to the Black Rock seeking adventure, with our fancy notions and city folk hubris. And we got more adventure than we bargained for. The desert trapped us, swallowed us up, repeatedly fucked with us. When it briefly lost interest in its pitiful captives, we beat a hasty escape, grateful to be back within predictable, if expected, reality. When Bob and I tell our little adventure story, I can’t help noticing the subtle wry smile crossing his face, that glint of something that says what we are both thinking—maybe we’ll just have to go out and trying it again next year. We came to the Black Rock seeking adventure, with our fancy notions and city folk hubris. And we got more adventure than we bargained for. The desert trapped us, swallowed us up, repeatedly fucked with us. When it briefly lost interest in its pitiful captives, we beat a hasty escape, grateful to be back within predictable, if expected, reality. Postscript Last year I saw on Facebook that Allen, the leader of the group who rescued us, leaped to his death off the Forest Hill bridge in Auburn. Very sad news. I really didn’t have any contact with him after our trip, aside from a few messages exchanged about trying to get together sometime. Who knows what happened? All I know is he was kind to us and had a generous, peaceful, artistic spirit. Our paths crossed just once, in such a remote, unlikely place. RIP. 2017 © Copyright Justin Panson. All rights reserved. Of Related Interest A remarkable sermon by Brian Baker, Dean of Trinity Cathedral, Sacramento, called Welcome Home—a Reflection on Burning Man. Baker describes his experience and the spiritual dimension he found at the festival. Watch it, and also watch his TED Talk. |

|

© Copyright Confluence Studio. All rights reserved.

|